America the Beautiful Park in Colorado Springs has a complicated history. Dozens of families, many made up of racial minorities, were gone when the city decided to raze the neighborhood and park there in the 1990s and early 2000s. But for former residents of the Conejos Neighborhood in Downtown Colorado Springs, the change was not painless.

Josie Ontiveros thinks America the Beautiful Park, a flagship public lands asset of the city’s downtown, at least has a descriptive name. It is beautiful, she said, but she never comes here. Normally, that is.

With the city recently celebrating its 150th anniversary this summer, Ontiveros returned to the land that once held the neighborhood where she was born and raised more than eight decades ago.

“I got a bunch of Kleenexes. I said, ‘Oh my God, I’m going to sit here and cry’ because I could see myself with my mom and dad,” Ontiveros said.

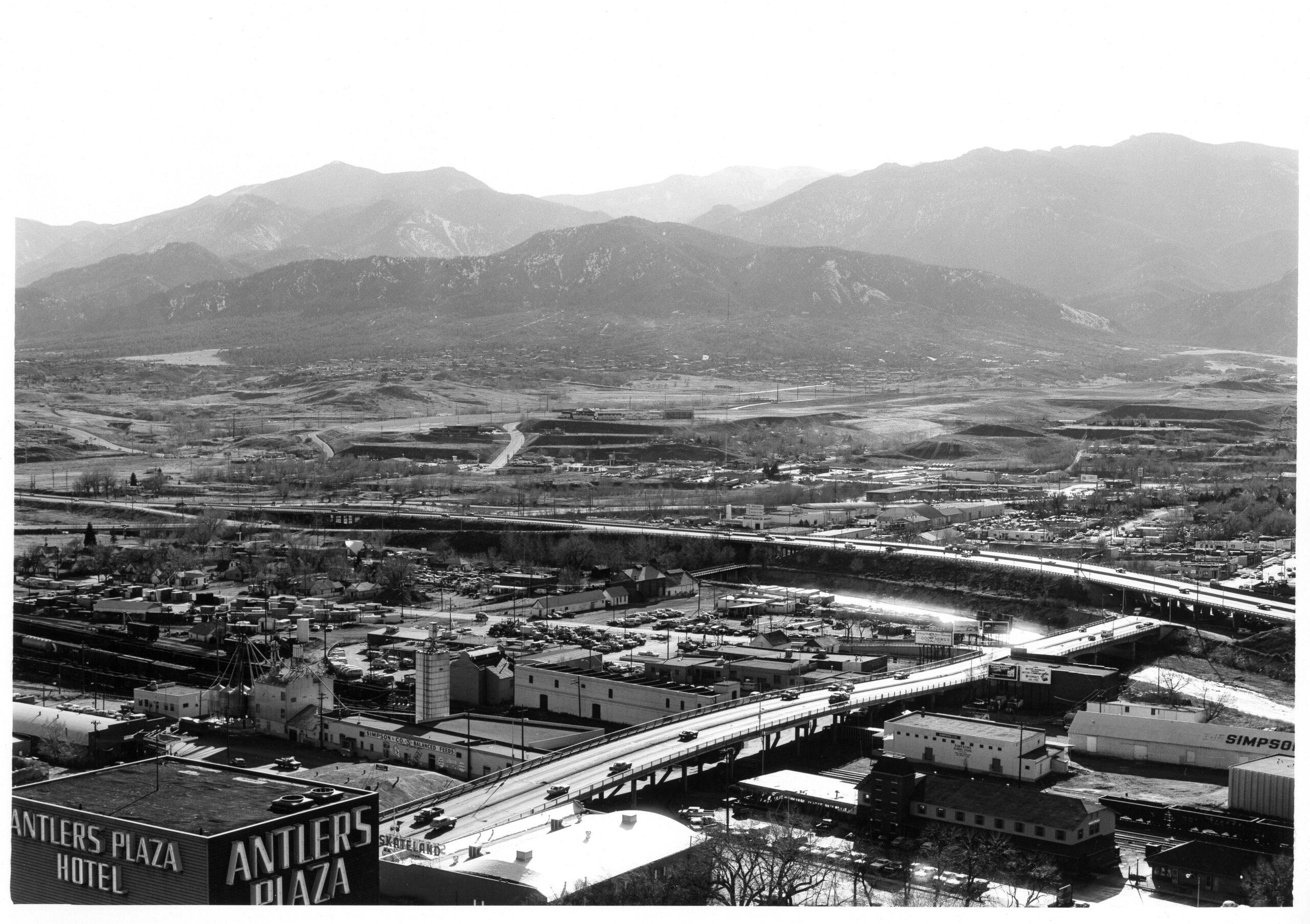

The 16-acre park is now easily reachable from downtown via an eye-catching 250-foot pedestrian bridge spanning a wide railway. Yet, just a few decades ago and for more than a century before that, that same railway formed the eastern edge of a small and vibrant working-class ethnic community known as the Conejos Neighborhood.

“They ran the trains, they worked on the tracks, they built the buildings, they hauled the trash. These are people that literally built Colorado Springs and they’re important,” said Leah Davis Witherow, curator of history at the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum. Davis Witherow recently put the finishing touches on a new permanent exhibit at the museum dedicated to the Conejos Neighborhood. She describes the neighborhood as a victim of decades of deliberate neglect from city leadership, an almost invisible poster-child for the type of ethnic displacement seen today in gentrifying urban areas around the country.

“We can’t understand Colorado Springs unless we include Conejos and lots of other stories that have been left out in the past. And, it’s more important than ever to have a more inclusive, complex, complete understanding of our history,” Davis Witherow said. “Otherwise, we’re just marketing.”

Una Familia Grande

Platted as the “monument addition” in the 1880s, named for Monument Creek which still marks the western border of the land to this day, Davis Witherow said Conejos was a neighborhood with a diverse ethnic population from the beginning. It was the site of the city’s first synagogue. And in the 1920s and 30s it became home to a largely Hispanic population from Southern Colorado and Northern New Mexico.

Josie Ontiveros was born in the neighborhood during that time. Her family lived in one of two yellow homes owned by the DNRG railroad. Her father worked for the nearby depot and they lived rent free. The home had electricity but no running water. They used an outhouse behind the home.

“This was a whole neighborhood,” Ontiveros said as she looked out to the park’s field of empty grass. “It looks so small. Now, I say ‘How did all these houses fit there?’”

Dozens of families lived in the cramped and isolated four block area. Nevertheless, Ontiveros described the neighborhood as a safe and welcoming place, filled almost entirely with Latino families caring for each other’s children playing in the dusty, unpaved streets.

It was the remarkably intact memory of her childhood and lasting personal connections that formed the basis of the Pioneers Museum exhibit, named “Una Familia Grande” in honor of the neighborhood’s tight-knit nature. Ontiveros drew a map of the Conejos neighborhood from memory to help Davis Witherow in her efforts to compile the exhibit, complete with which family lived in which home.

“Block by block by block, she named every single one,” Davis Witherow said. “ I think that demonstrates how interconnected (they) all were.”

‘Consciously Neglected’

Davis Witherow said the fate of the neighborhood tracks with a lack of investment in minority neighborhoods around the country. Over succeeding decades in the 20th Century, Conejos lacked basic infrastructure improvements put in place across the rest of downtown — including street lamps, sidewalks and paved streets.

”Because largely of the working class, Hispanic and black populations here, they are not top of mind for the movers and shakers — the decision makers in Colorado Springs,” Davis Witherow said. “Over time, the neighborhood became blighted.”

In the 1990s, the city began offering buyouts for Conejos residents, eventually leveling the few remaining dilapidated homes to make way for the park that opened at the site in 2005. Davis Witherow said the former residents she has spoken with feel many different ways about the area today.

“Some people are angry that their neighborhood was destroyed and that they put a park right on top of it. Other people actually like the fact that once again, this is a place that draws families and there’s music and there’s happiness in it,” Davis Witherow she said. “But, it depends on who you talk to.”

Ontiveros said she fears the neighborhood could be forgotten. America the Beautiful, while a descriptive name, does not honor the history of the land, she said. On the south end of the park, the Chadborn Community Church is the last remaining building from the neighborhood, facing the one small strip of road still named Conejos.

Slideshow: Conejos Today

Better Stewards

Colorado Springs Mayor John Suthers said in a statement to CPR News that the story of the city is a complex one and he admits leaders of previous generations could have benefitted from community planning processes, building codes and the cultural norms of today.

However, Suthers said he believes Colorado Springs has learned the value of preserving neighborhoods and their culture. He noted two of the eight pillars in the city’s municipal planning document are dedicated to such causes.

“While the vibrancy of the Conejos neighborhood was lost to growth in our past, it’s my hope that as more mindful people, we will be better stewards of our history and our present as our city grows,” Suthers wrote.