Taking a walk around the grounds of Meeker’s famed sheep dog trials, at first it seems pretty sedate. Some clapping and a murmur of voices can be heard from the stands, along with the bleating of penned-up sheep on the sidelines, unknowingly waiting for their turn in the spotlight.

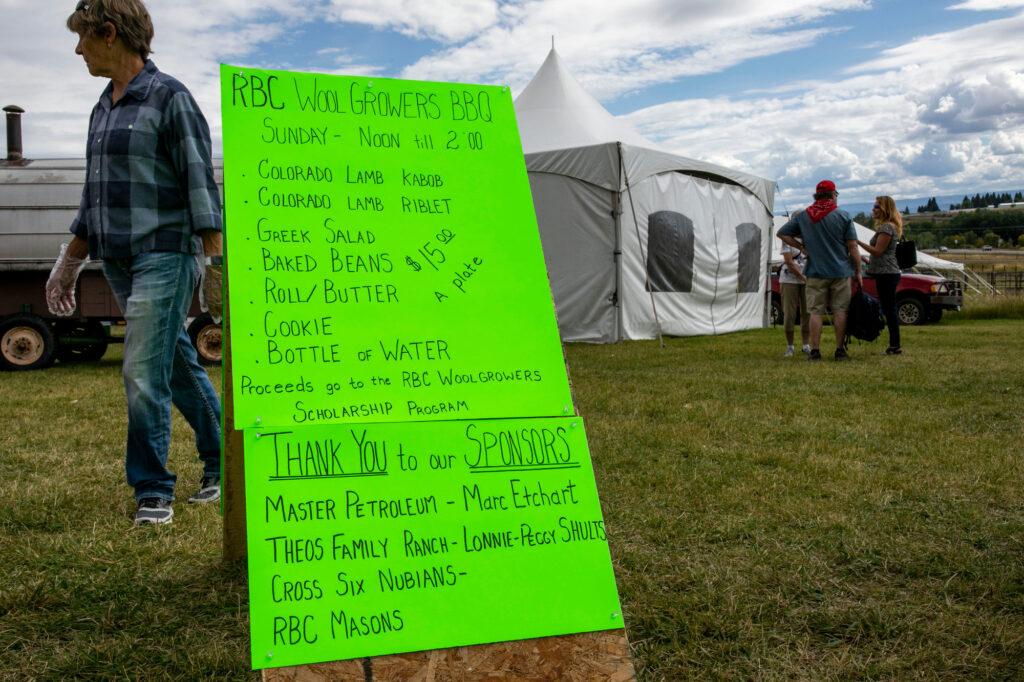

People eat and amble through a small festival area, past a vendor selling wooden signs that declare “Border Collies Leave Pawprints On Your Heart.”

But sitting in the bleachers, on this final day of the Meeker Classic Sheepdog Championships was a roller coaster. With a full view of the vast, electric-green field, spectators could see every success and misstep made by the handler, directing her black-and-white dog with a whistle. The quietness was, in fact, intense concentration by everyone watching.

Rita Larson’s eyes were big. “No, no, no, no, no,” she uttered, like it was painful to say, as the dog kept almost herding the sheep into a pen, but not quite. The sheep kept escaping. But then finally, like a stroke of magic, the crouching dog persuaded them in.

“Look at that!” exclaimed Larson’s friend, Jean Kochersperger, as everyone around them clapped. “Look at that!”

These are the moments that keep these two retirees coming year after year, Larson from Grand Junction and Kochersperger from Magnolia, Texas. They make sure they get into their favorite seats, right in the upper corner of the bleachers, not long after 7 a.m. They stay until the last dog runs.

Rapt attention as the spectators hang on their every move

There’s no wandering around, no doing a crossword or knitting during these trials. The women carefully examine each move — and get emotionally invested in each dog.

“Yeah, I go home exhausted,” Larson said, laughing.

“We work as hard as they do,” Kochersperger joked.

They come prepared for rain, snow, sun, wind — they’ve seen it all. Kochersperger even writes down how each dog does. That’s even though neither of them owns border collies. Larson used to, but hers died years ago. Still, the women remain delighted sheepdog groupies.

“They have such heart,” Larson said, with a huge, fond smile. “And they work so hard. They’re just great.”

These dogs — all 170 that took part in the nearly-weeklong trials — are celebrities here. People gush about them, talking up how smart and loyal they are, how they hardly even bark.

Most, like Kip the border collie, just silently take in this whole scene. He’s almost entirely black with golden eyes, which his handler, Diana Sylvestre, calls “wolf-colored.” She thinks that’s why sheep respect him so much.

“He's obsessed with sheep. He's obsessed,” she said, holding onto Kip’s leash. “If you watched him before our run, he was watching, hypnotized by the sheep.”

'This is one of the best trials in the United States'

They’re not professionals, Sylvestre explained, and they split their time between Oakland, where she’s a doctor, and her Northern California ranch. But in the five years they’ve been competing together, she’s seen Kip transform.

“You take this little puppy that's afraid of everything, and suddenly they become this self-confident powerhouse and bring you along in so many different ways,” she said.

They even made it into the day’s finals — the top 12 dogs. They won’t win, but Sylvestre was honored to be here.

“This is one of the best trials in the United States,” she said, “if not the best.”

And this is in a town of just a few thousand people. It all started in 1987 when Meeker was in need of an economic boost. Someone suggested a sheep dog trial could do the trick, so then-mayor Gus Halandras decided he’d figure out how to put one on, despite the fact he had no experience at all.

“There’s no formula,” he said while watching the finals. “You just get lucky and never quit.”

That first year drew 76 dogs and a few thousand attendees. It’s more than doubled in size now — and has been growing in popularity ever since (save for a pandemic pause in 2020). Every year, it brings about $1 million into the local economy.

Halandras loves to travel and has met Meeker Classic fans all over the world.

“Let people know you're from Meeker, Colorado, and all of a sudden you're starting to talk dogs,” he said.

Halandras and his wife headed to the stands to watch a particularly famous handler. Wearing a pageboy cap and a tie, he guided sheep through a series of complex, prescribed moves. The wooly, off-white bodies moved together like starlings, gliding in formation across the grass.

Time was running out

There was only one move left for the man-dog pair: persuade the sheep wearing collars into a pen, without touching them, and close the gate. But the sheep kept bolting away at the last moment. They would get so close, then deflect the gate, bounding away.

Halandras looked nervous. Time was running out — quickly.

“Thirty-four seconds. Can you believe that?” he said, in disbelief.

The dog and her handler had started with 30 minutes. The next few seconds ticked by full of tension, people literally grabbing their seats, their eyes glued to the impossible scene.

Soon, there were 10 seconds left. Nine, eight ...

Halandras’ wife, Christine, was one of many people muttering much the same thing: “Please go, please go, please go.”

Six, five, four ...

Then, somehow, the dog escorted the sheep in. It looked like one was going to bolt, but it stayed. The handler closed the gate. The crowd erupted.

They had made it, with only two seconds remaining. A truly cinematic moment.

“Isn’t that exciting?” yelled Gus Halandras, over the screaming crowd. “They would do this for Tom Brady!”

After the delirium, handler Scot Glen and his 10-year-old sheepdog Alice walked off the field, triumphant and humble. Glen said he got “lucky.”

“If I could have got lucky about 10 minutes earlier, my heart would be in better shape,” he joked.

But for Glen, visiting from Alberta, Canada, that uncertainty is part of his addiction to this sport. He described it as impossible to “master.”

“You'll have the odd time you'll be close to mastering it, but you'll never master it,” he said.

There may always be “another beast out there that shows you that you're not as smart as you thought you were,” he said, with a relieved laugh.

He didn’t know yet, but they had won the entire championship. Next month, they’ll compete at the nationals in Virginia, which they’ve also won before. Glen hopes Alice will get to be top dog there one more time before she retires.

Editor's note: In a previous version of this story, captions on three photos misidentified where handlers Christine Jobe and Scott Glen live. Both are from Alberta, Canada. The captions have been updated to reflect that.