Indigenous enslavement was widespread in Southern Colorado during the early- to mid-1800s.

The Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center in the San Luis Valley is hosting a free, bilingual and virtual event exploring this history on Thursday, Sept. 30, at 6 p.m. Researcher James F. Brooks will present on the intercultural slave system of the Southwest Borderlands, with particular attention to the region along today’s Colorado-New Mexico border.

The talk coincides with an installation titled "Unsilenced: Indigenous Enslavement in Southern Colorado." The exhibit is part of a larger Borderlands project at History Colorado’s southern Colorado museums. There is no end date scheduled for the exhibit.

The museum's director Eric Carpio spoke with KRCC’s Shanna Lewis.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Who were the enslaved people in the San Luis Valley?

It's a history that not a lot of people are aware of. In this region and the San Luis Valley, as well as throughout other parts of southern Colorado and what was New Mexico Territory at the time, there was a practice of Indigenous peoples being held captive in people's homes across the area. This was a pretty regular occurrence, it wasn't unusual at the time. The largest number of individuals enslaved were the Diné or Navajo. But there's also a number of Ute individuals, Paiute and even captives from outside of the immediate region.

How did they become enslaved?

There were a lot of different ways that a family may have acquired a captive. It could have been through capture, through a raiding process. There were also captives who were captured and then sold on the market and purchased.

The exhibit features large photos of captives. How do the images affect viewers?

They're really powerful. Particularly as we combine what we see in the images with the stories that we've heard. We've worked with tribal partners, as well as a lot of descendants who have traced their lineage back to this history.

It's often a story about loss and erasure and about trying to understand this history, this close connection to their history and their lineage, that they feel has been either lost or stolen or erased. And so when we look at the photographs, particularly with the young men in these images, often they're dressed in what we'd consider more Americanized clothing, with suit jackets, collared shirts and short hair. It really is reminiscent of this loss of identity and forced assimilation.

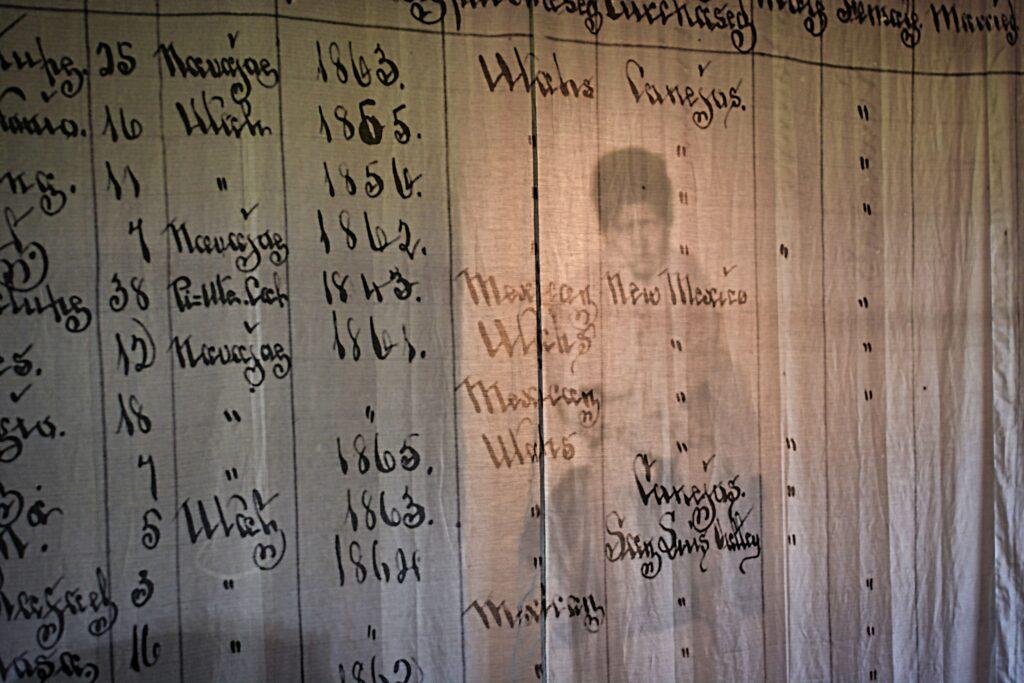

There are also huge photos of long handwritten lists. What are those lists and who wrote them?

Those images are reproductions of a census known as the 1865 Indigenous Captive List administered by Lafayette Head. He's the Indian agent for the Ute in southern Colorado. Of course, 1865 is after the Civil War, after the Emancipation Proclamation. Indian agents here in the region at the time were directed to try to understand and document this practice of Indigenous captivity.

One of the ways in which Indigenous enslavement is different than the African and African American enslavement that we're more familiar with what took place in the south… Indigenous enslavement was never legal in this area. There wasn't a lot of documentation of this practice, a lot of it happened underground. So the documents that we have in the exhibit are fairly unique in that it really clearly outlines and is proof really that this practice exists.

In addition, we also have a copy of a letter that was sent from Lafayette Head to Governor Evans, who's the governor of the Colorado Territory at the time. If you read the letter, it really comes across as this is a surprise to him (Head), that he's surprised by this practice. He's outraged. I believe he says in the letter that this practice is barbarous and inhumane.

But what he doesn't mention is that he has captives in his home. They end up not being listed on the census that he submits to the governor, which ultimately ends up in Washington D.C. So he's also complicit in this practice.

Why are so many of the names on the lists either Anglo or Spanish?

It was common then when an Indigenous person would be taken captive and brought into the home that their name would be changed to reflect the language of the household.

What did it mean for the people whose names were changed?

This is really one of the most tragic parts of the story. One of the most striking parts of looking at these documents is that we've got a list of individuals who are listed as captives. Clearly, the names listed are not their given names that they were probably given by their own family or their own tribe. That alone is just indicative of that loss that these individuals have experienced firsthand in the moment, but also the loss that is then passed on to their descendants.

How are people in the local community responding to the exhibit?

It's not uncommon to hear families who've come to the exhibit talk about the stories that they've heard from parents and grandparents about the possibility of being Indigenous or about having an Indigenous enslaved great-grandmother or great-grandfather. And oftentimes, that history has been either denied or repressed or hidden. I've heard from several people who've said that this really begins a healing process, in the way that they understand their own history and their identity and their community.

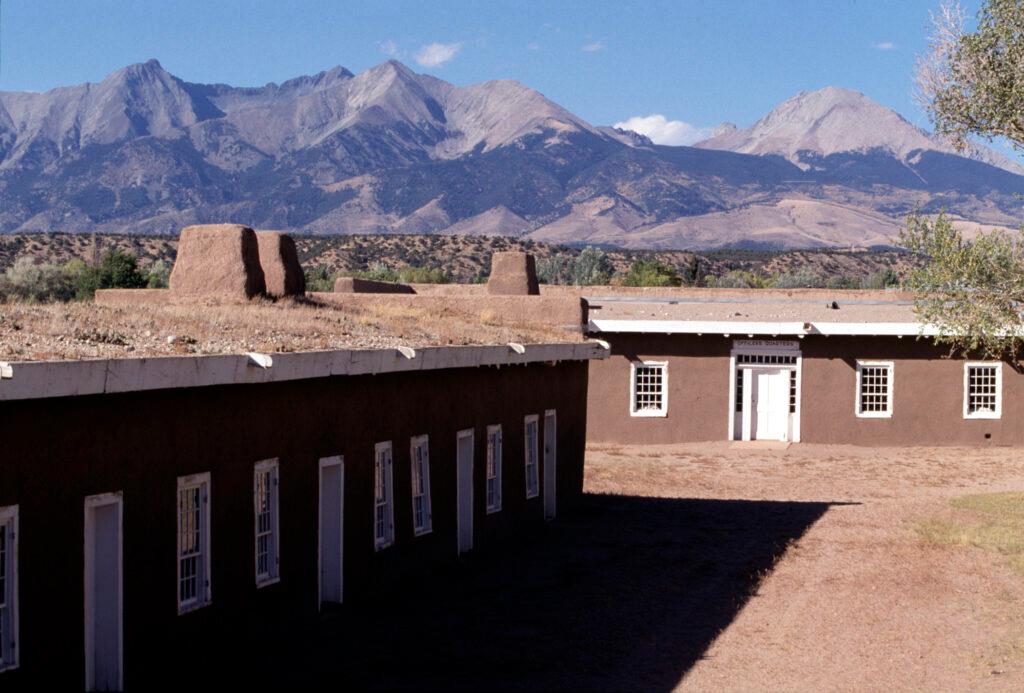

How does this exhibit compare to what’s been on display at the Fort Garland Museum?

This museum has primarily told the military history of the fort and this region. A lot of the exhibits were intended to evoke what it may have been like during that time period when soldiers were here and the fort was active. We have five original buildings on the property that were built in 1858 when the fort was established. But this particular exhibit is in the space that was the Commandant's quarters, where for 68 years, there was an exhibit devoted to Kit Carson and the military. Carson was stationed here at the fort for 18 months towards the very end of his career. This was his last assignment before he retired.

So, this exhibit is a departure, it’s the first exhibit that signals a new direction for the museum. It is not the traditional way that we have done exhibits. This one is in conjunction with an artist, so it is as much like an art installation as it is a history exhibit.

The way Chip Thomas (a.k.a Jetsonorama), the artist, presented this work, it touches people at an emotional level, yet also makes absorbing the information accessible and understandable. It's not heavy with interpretation, we want to provide enough so that people understand the history and the stories and can think about the impact and the way that that has continued to affect the way that families here in the valley see themselves and their community.

We also want to invite people in to share because we don't know everything about this history because it hasn't been studied as much. So we're offering the community to come along on this journey with us and help us discover more. This particular exhibit is really the beginning of what we hope is a larger conversation.

The lecture "The Tomorrow of Violence: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Borderlands" is Thursday, Sept. 30, at 6 p.m. The installation "Unsilenced: Indigenous Enslavement in Southern Colorado" has no set closing date.