Javier Del Castillo of Denver was looking for a safe, reliable vehicle for his teenage daughter that could also haul skis, dogs, and the whole family for occasional trips to the mountains.

The vehicle they ended up buying, a 2008 Lexus RX 400 sport utility vehicle, came with another bonus: a tape deck.

“My kids were wondering, ‘What is this thing?’” Del Castillo said with a laugh.

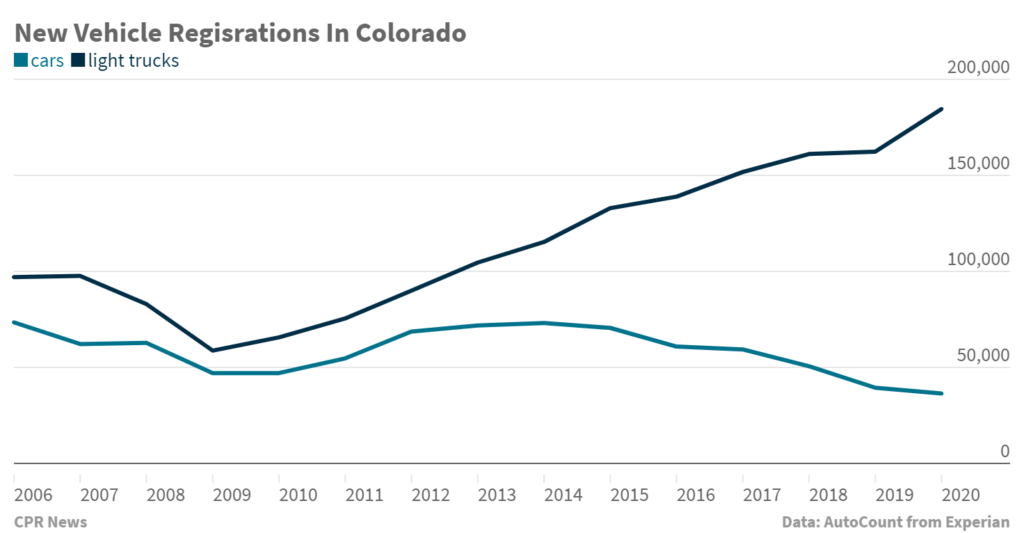

SUVs have long been popular in Colorado, but ownership has exploded over the last decade as the number of passenger cars on the roads has dwindled.

Industry data shows light trucks, including SUVs, now account for 86 percent of new vehicle registrations in the state so far this year — second only to Vermont.

The benefits — higher clearance, spacious interiors, and often, four- or all-wheel drive — are clear to people like Del Castillo.

But there are less-talked about downsides to Colorado’s love affair with SUVs and trucks.

SUVs are often advertised rumbling through beautiful mountain valleys.

As it turns out, drivers are trying to do that in real life, too. In the Gothic Valley outside of Crested Butte, conservation workers often find tire tracks gashed through meadows of wildflowers and other greenery.

“Someone sees these tire tracks, and they’re like, ‘OK, like, somebody already drove here. I can drive on this.’ And they’ll go a little bit further and impact it a little bit more,” explained Jake Scott with the Crested Butte Conservation Corps. “And this will happen all summer long, over and over again. Until then, there’ll be a road there.”

Scott and his crewmates line the valley’s roads with giant boulders to keep high-clearance vehicles out of vulnerable areas. The U.S. Forest Service recently clamped down on dispersed camping in this valley and others nearby to better protect them from vehicle damage and other abuse.

Such destruction is a growing problem across the Forest Service’s public lands, said Rebecca Robbins, spokesperson for the San Juan National Forest.

“We have seen increased damage over the past two years as more people are visiting the forest in search of isolated dispersed camping sites,” Robbins wrote in an email. “Those in search of solitude are traveling farther afield to distance themselves from other campers.”

People have ignored signs and tried to drive around Clear Lake near Silverton, which lies at the end of an off-road trail at nearly 12,000 feet, Robbins wrote. Delicate environments like that often have short growing seasons and contain fragile plants that do not recover quickly.

“We ask that people utilize existing dispersed campsites and not create new ones,” she wrote.

Still, the high country is where SUVs shine. They can be fatal in the city.

Researchers have known for decades that vehicles with high front ends are more likely to kill or severely injure pedestrians than passenger cars. A truck, SUV or van is more likely to injure a pedestrian’s vital organs in their torso or head than smaller cars that more easily strike a person’s legs, propelling them over the hood.

“Being struck by a car is still quite bad, but it’s much less bad than being struck by a larger vehicle,” said Justin Tyndall, assistant professor of economics at the University of Hawaii.

The rise of SUV ownership — and the biggifying of pickup trucks — means there are far more potentially deadly large vehicles on the road. In a recent journal article, Tyndall analyzed fatal crash data and vehicle registration data between 2000 and 2019 to estimate that the increased popularity of larger vehicles and the decline of cars accounted for an extra 1,100 pedestrian deaths across the United States.

In Colorado, pedestrian deaths more than doubled from 40 in 2010 to 93 in 2020 — a record high. Data from the Denver Regional Council of Governments, which has a goal of zero traffic deaths, show that most fatal crashes that kill pedestrians and cyclists now involve SUVs, trucks and other large vehicle types.

Tyndall acknowledged other factors beyond vehicle size contributed to deadly accidents, including smartphones distracting both pedestrians and drivers. Lower speed limits and better road designs that separate vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians would help, too.

Tyndall said his data and other sources suggest that larger vehicles are safer for occupants. But given the danger they pose to others, Tyndall said policymakers could consider imposing higher taxes on them to discourage their wide adoption, as France did recently.

“They're sort of a luxury item,” he said. “I don't think we would have to be too concerned with equity.”

An electric SUV — or any vehicle for that matter — is not climate-friendly.

New SUVs are not the gas-guzzlers their ancestors were, and electric SUVs are responsible for fewer greenhouse gas emissions through their life cycles. That doesn’t mean they’re environmentally friendly, said Alexandre Milovanoff, a researcher in sustainable transportation at the University of Toronto.

“They're not good for the environment,” Milovanoff said. “They're just less bad.”

SUVs are typically less efficient than similarly powered cars because they are heavier, Milovanoff said.

He recently co-authored a study that suggested the electrification of passenger vehicles isn’t sufficient for the U.S. to reach its target of preventing a temperature rise of 2-degrees Celsius. Another report found that carbon emissions from SUVs actually grew in 2020, even as overall emissions fell because of the pandemic.

While much of the push to reduce greenhouse gases relies on government and private sector action, consumers are especially important when it comes to transportation. That sector is now the single largest source of all climate-warming emissions in Colorado, and state officials say cutting those is the “most complicated” piece of its reduction plan.

Biking, walking and public transit are by far the most climate-friendly way to move, Milovanoff said. But much of the U.S, Colorado included, was built for motor vehicles and navigating it without one is treacherous. In such cases, Milovanoff said, Coloradans should get the smallest, most efficient vehicle possible.

“We’ve lost this ability to ask ourselves, ‘What do we need?’ And we go toward things that we think we want,” he said.

Javier Del Castillo, who’d just purchased the Lexus, said he cares about pedestrian safety and the environment. But his daughter’s safety is his top priority, he said.

“If she does get t-boned, I’d rather it happen in a car like this,” he said of the Lexus. “You place a priority on your own and your family. It’s a trade-off.”

He also likes the lifestyle his SUV enables and doesn't think they are incompatible. Del Castillo pointed out that the Lexus is a hybrid and said he rides his bicycle to work two or three times a week in the summer.

Del Castillo said his next vehicle will almost certainly be electric. And because he already has an SUV, he thinks it'll just be a car.