The state Supreme Court is accepting challenges to Colorado’s new congressional election map through this week. At least two groups say they will file their concerns about the map, which was drawn by the state’s first independent redistricting commission.

Among the contentions: that it does not adequately represent Latinos and other minority groups and dilutes their voices.

The independent redistricting commission sent the map to the Supreme Court on October 1 for review. The court has until November 1 to approve it, or the map goes back to the commission. In the meantime the court will evaluate whether the independent commission correctly fulfilled all of the constitutional criteria in the final map, and take into account the legal challenges from groups unhappy with the outcome.

If the justices reject the map, the commission would meet again to try to address the court’s issues.

Latino groups say commission overlooked their community

CLLARO, the Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy and Research Organization, is one group objecting to the map as drawn. It said the map fails to adequately represent the Latino community.

“This is an incredibly disappointing outcome for Colorado Latinos, communities of interest, and Colorado voters as a whole,” said a written statement from the organization. The group argued that the map does not fulfill the criteria the commission was supposed to follow, set up by voters statewide in 2018.

“Voters were crystal clear in 2018: communities of interest should be preserved and prioritized. It’s remarkable that the Commission disregarded the will of the voters by prioritizing an arbitrary competitiveness target over communities of interest.”

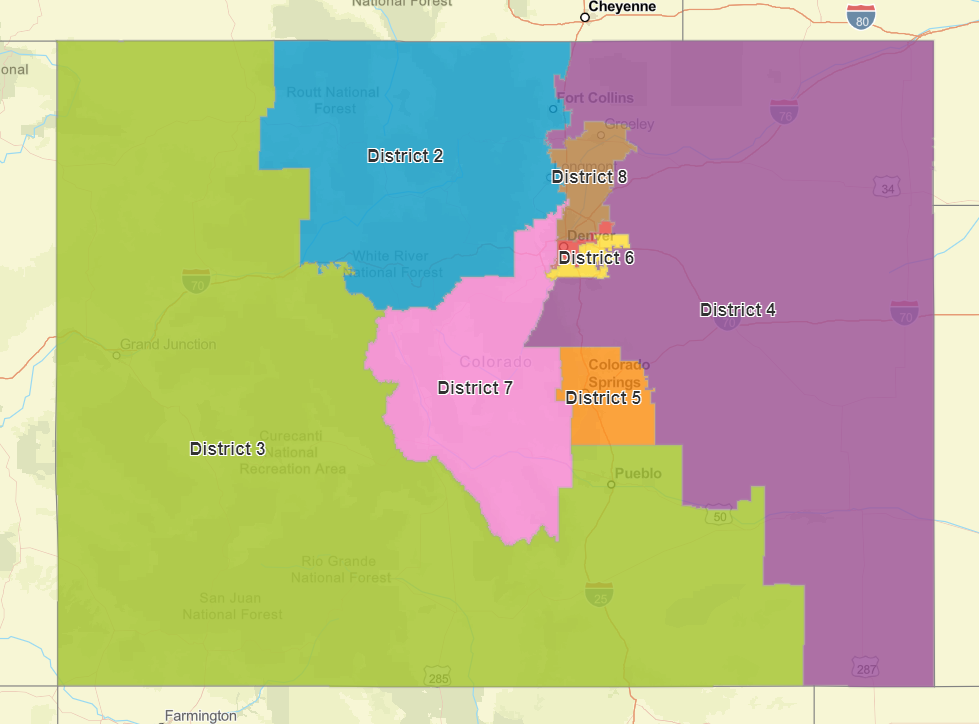

The new congressional map is largely modeled after Colorado’s current boundaries, but some groups like CLLARO and the lone no vote on the map, Democratic commissioner Simon Tafoya, advocated for a southern Colorado congressional district. They say the commission prioritized competitiveness over communities of interest.

The League of United Latin American Citizens will also file a brief with the court laying out concerns, which are also about the southern part of the state.

“There is a large Latino population in Southern Colorado, the San Luis valley, Pueblo, Southern Colorado Springs,” said Mark Gaber, director of redistricting at the Campaign Legal Center and representing LULAC.

“It's not just a matter of how many Latinos are in a district, but it's an analysis of the election returns to see if those show that Latino voters together with some white voters who support Latino candidates of choice, if they would be able to coalesce together and elect their preferred candidates.”

As it stands, the southern region of the state would be in a safe Republican district.

Gaber also has issues with the newly created 8th congressional district north of Denver. It’s close to 40 percent Latino and would be the only competitive seat.

“To achieve the competitiveness goal by making the most substantially Latino district, the one where white Republican voters are most likely to be able to elect their candidate in that district, is basically the definition of diluting Latino votes.”

Colorado's eight seats could be split evenly among Democrats and GOP

Politically the map creates four Democratic seats, three Republican ones and a swing district — the eighth — that leans slightly to the left. The boundaries give all of Colorado’s current members of Congress a strong chance of holding onto their seats.

The map Tafoya envisioned had five Democratic and three Republican seats. Before they voted to approve a map commissioners were locked in a lengthy discussion about how best to represent rural parts of Colorado, ensure representation for different racial and ethnic communities and account for the state’s political interests.

“I cannot move forward a map that has not one single competitive district,” said unaffiliated commissioner Lori Schell.

Some Democrats may be thinking back to what could have been. Had voters not approved an independent commission, Democrats would have been in charge of drawing new political lines because that party controls the state legislature and Governor’s office, which is the way electoral maps are drawn in most other states. But other progressives believe that having an independent commission was worth the sacrifice.

“As a partisan operative, would I have liked six safe Democratic seats? Sure,” said Democratic political strategist Ian Silverii.

“In terms of realistic outcomes that honored the state constitution, respected communities of interest and created a fair map. I think this gets pretty close.”

Republican former State House Speaker Frank McNulty, who advocated for the new process, said after seeing the commission’s final map that he was grateful that the state’s newest congressional district would be “highly competitive.”

Despite some tense moments and accusations, commissioners all praised the months-long process it took to get to a final map, which was based off of a plan from non-partisan staff that relied on public input.

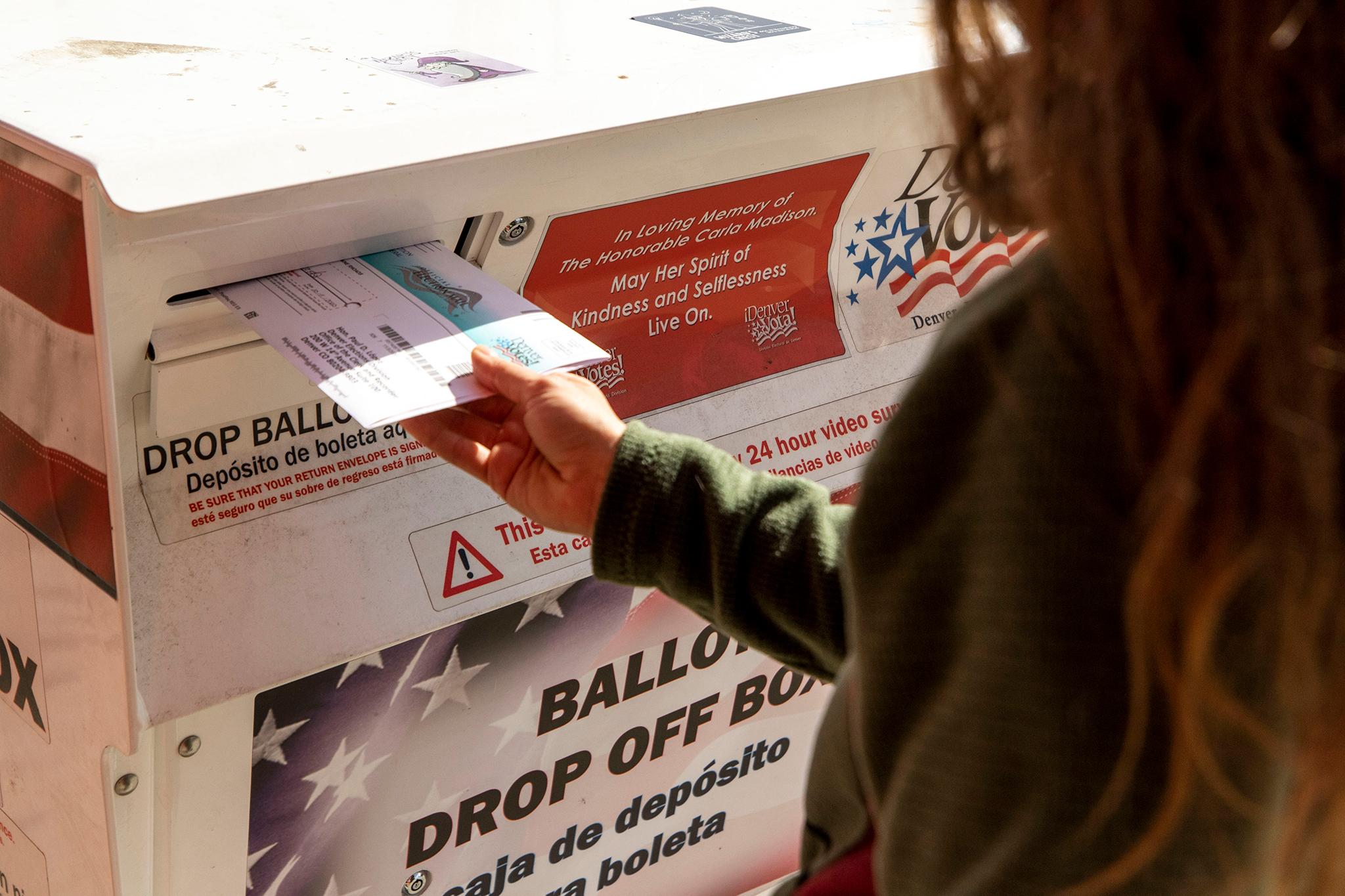

“I feel like I'm part of a community,” said unaffiliated commissioner Jolie Brawner. “ And in reading all of the comments, all over 5,000 of them, I would keep reading them. I think it was so amazing how involved everyone was in this process. And I think it was really fantastic that we got to be part of this first group that had the public more involved in this process than they've ever been before.”

The commission, composed of four Democrats, four Republicans and four Unaffiliated voters approved the map 11-1 after six rounds of voting.

Even Gaber, said despite his concerns, he doesn’t have issues with how the commission worked.

“The fact that there were so many hearings across the state and it was so easy to provide public input, that's all fantastic, and the Colorado constitution sets out clear guidelines for the commission to follow.”

Criteria for Drawing Congressional District Map

Districts must:

- Have equal population, justifying each variance, no matter how small, as required by the U.S. Constitution;

- Be composed of contiguous geographic areas;

- Comply with the federal "Voting Rights Act of 1965," as amended;

- Preserve whole communities of interest and whole political subdivisions, such as counties, cities, and towns;

- Be as compact as is reasonably possible; and

- Maximize the number of politically competitive districts.

Districts cannot be drawn for the purpose of:

- Protecting incumbents or declared candidates of the U.S. House of Representatives or any political party; or

- Denying or abridging the right of any citizen to vote on account of that person's race or membership in a language minority group, including diluting the impact of that racial or language minority group's electoral influence.