Two years ago, Colorado made a promise: No one should have to wait in jail — before they’re convicted of anything — for more than 28 days for mental health restoration if they’ve been deemed incompetent to stand trial.

But currently 347 people have been either awaiting pretrial evaluations or mental health restoration for longer than that. Some for far longer. One person has been waiting for 325 days.

It is the longest backlog for mental health restoration in years and Colorado will have to cough up millions of dollars in fees compelled by a federal consent decree because of it.

But the cost is really felt by the people inside the system.

“I truly believe if he would have gotten the help he needed, he’d be alive today,” said Anne Pyle, whose 42-year-old son, Michael Pyle, took his own life in May in the Adams County Jail while waiting to get transferred to Pueblo for mental health restoration. “If he would have been transferred to a safe space, he would have gotten the help.”

Pyle is one of at least two people who have completed suicide in jails this year while awaiting restoration services, according to police records and the court-appointed special masters overseeing a consent decree. The second is Danny Higbee of La Junta, who killed himself in the Bent County Jail in June.

Robert Werthwein, head of the Office of Behavioral Health at the Colorado Department of Human Services, called the wait times unfortunate because so many people in crisis are stuck inside facilities not made to treat mental illness.

“Some of these people are pretty sick, and that’s the hardest part, is seeing how sick some of these people are and not being able to move them (into treatment) quickly,” Werthwein said.

For more than a decade, Colorado has struggled to keep up with the high numbers of people with mental illness stuck in the criminal justice system.

There have been years of egregious delays — both for evaluating whether people facing criminal charges are competent to stand trial and for treatments to “restore” them to competency. Those can be medication, classes — whatever it takes so that the person charged with a crime understands the criminal charges against them and can assist in their own defense.

Roughly 30 percent of the people awaiting restoration face extremely minor charges — misdemeanors like public urination, state officials said. That can lead to them spending more time in jail waiting for treatment than they would serve if they had just been convicted.

“We’re talking really low level stuff — what they really need is outpatient, community-based treatment,” Werthwein said. “The real long-term answer for this fix is to stop using the criminal justice system to fill gaps in our behavioral health system.”

Promise to end problem runs into pandemic

Back in the 2010s, over the course of a decade, mental health advocates sued the state four times over the problem.

The last lawsuit was settled in 2019, when the state Department of Human Services and advocates from Disability Law Colorado reached an agreement: the state would pay between $100 and $500 a day per inmate waiting more than 21 days for an evaluation. There would also be fines when an inmate had to wait too long for treatment, depending on the severity of the mental illness. The money goes towards special projects, which have to-date focused on diversion programs, homeless services and housing.

In the first year, the fee was $10 million. The parties agreed to a flat $6 million earlier this year for additional delays.

In the year after the consent decree, the state began making remarkable progress.

Timelines shrank and wait times for the most severe cases did too, according to reports from the court-appointed special masters.

Some of the people with lesser illnesses were still waiting in jail for restoration longer than 28 days, but the special masters said the state was working towards getting out of the federal requirements — and fines — by the end of 2020.

“And then COVID hit,” said Neil Gowensmith, a special master appointed by the federal court on this case.

The Colorado Department of Health and the Environment serves as a licensee for the state’s largest mental health hospital in Pueblo and sets the rules for how many people can be admitted at a time. At the start of the pandemic, CDPHE officials slowed admissions into the hospital way down.

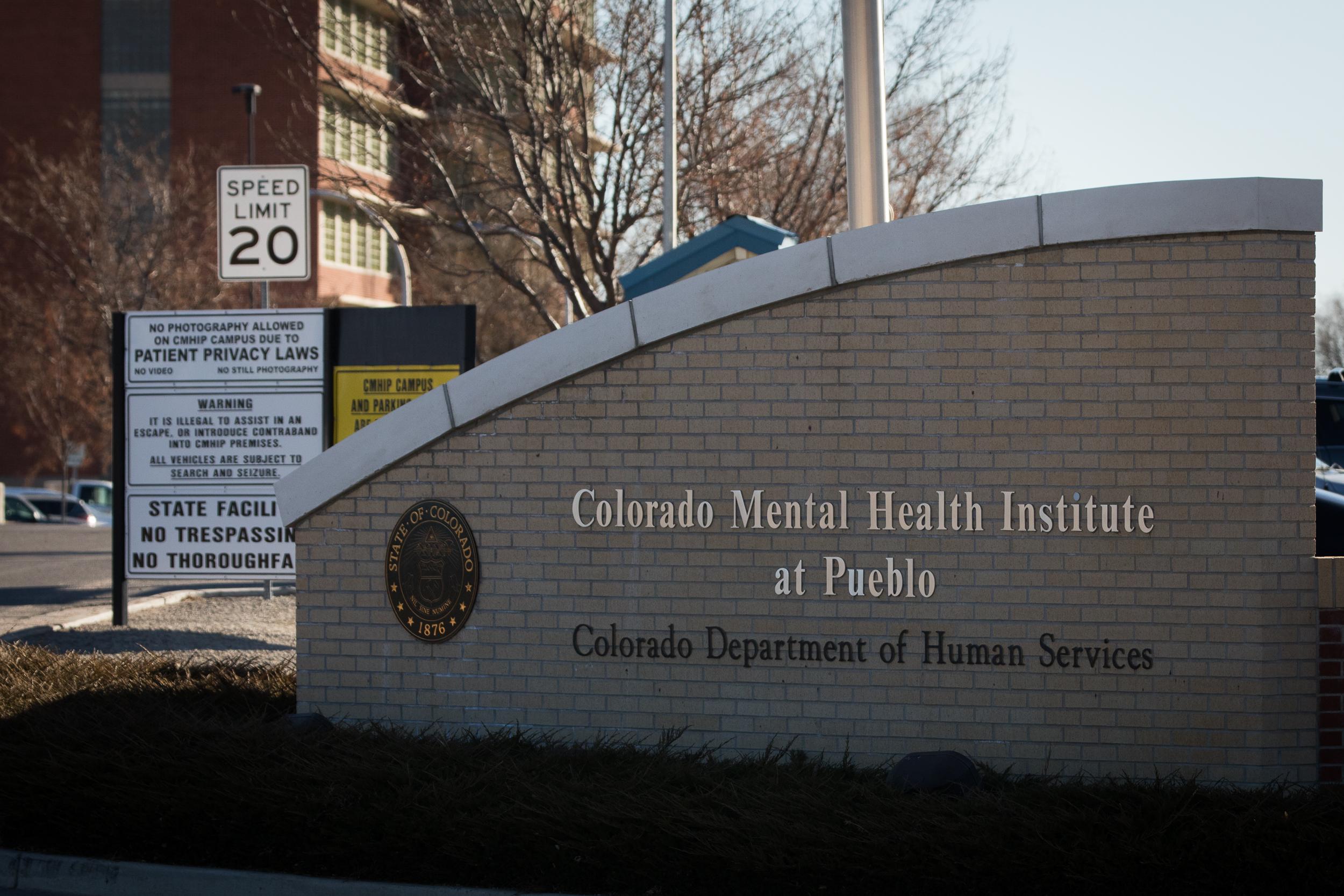

Although some Denver area jails have competency restoration programs, the hospital, called CMHIP for short, is where many people, particularly those with the most severe conditions, are sent for restoration from jails across the state.

At first, the court-appointed special masters Gowensmith and Daniel Murrie were patient with CDPHE’s reluctance to pack too many people inside the hospital. After all, the two also were worried about COVID-19 outbreaks and didn’t want to put people at great risk of infection because of their mental illness.

But as the waitlist to get restoration swelled to hundreds of people, the court-appointed special masters grew angry at CDPHE for shutting down so many beds in the name of pandemic restrictions.

At the same time, it wasn’t like the people awaiting treatment were safer in jail, where many were stuck for months. Some of the jail-based competency restoration programs were also stalled out due to COVID-19 outbreaks and staffing shortages.

“Ultimately we started to feel like these precautions to keep people from getting COVID … really were overshadowed by the much greater public health risk of people in jail with untreated psychosis,” Murrie said. “The rate of deaths from COVID is less than 1 percent, the rate of deaths from untreated psychosis is about 7 percent … People in the jail were not eating or drinking, or they were spreading their feces or at risk for suicide. They started to feel like real emergencies.”

‘I think he gave up’

Anne Pyle, who lives in Federal Heights north of Denver, felt that emergency every time her son Michael phoned from the Adams County Jail.

“His sickness was getting worse,” Pyle said. “I was not able to see him, no one could visit. When he would call me, a lot of times he was so delusional he didn’t even know who I was or thought I replaced his real mother, that I was a clone.”

Pyle’s most recent troubles started last winter when he led officers on a high-speed chase and apparently pulled a weapon on them, although cops later told his mother the gun was fake.

He escaped after the chase but felt so bad about it that he walked in the cold from Golden to Thornton to turn himself in to police there, Anne Pyle said.

Her son was in such bad shape when he got to the police department, Anne Pyle said, that they took him to North Suburban Medical Center for treatment. He was eventually transferred to the jail, where he was evaluated and deemed incompetent to face his criminal charges.

As he spent months in 23-hour-a-day lockdown, Michael Pyle’s mental health worsened.

He had been diagnosed with schizophrenia about eight years ago. Michael Pyle told his mother he heard voices screaming and being tortured in his head, that he would shut his eyes and see bodies melting.

But with some treatment and medication, he stabilized. His mother said he taught himself Russian and Spanish, got a commercial truck driving license and worked in the oil fields.

By the summer of 2020, he had an excellent job driving a truck, Anne Pyle said. He was renting an apartment in downtown Denver, had just purchased a motorcycle and was doing well.

When the racial justice protests started, though, the voices came back, he told his mother.

The screaming and torturing sounds were triggered anew by the chants on the streets below his apartment. The tear gas, the guns, the disruptions were all hard for him to listen to without hearing his own demons when he shut his eyes, she said.

So, even though Michael Pyle had just paid his rent, he packed up his truck and drove to his mother’s house, where he confided to his mother that he felt like he was getting worse and he needed some serious help.

The two tried calling every mental health treatment center they could find. Only two accepted Medicaid and the one in the metro area had a long waiting list to get in. Pyle got a list of doctors who could possibly help — he called every single name but no one got back to him.

“He never got the help,” Anne Pyle said. “And I think he gave up.”

In May, a victim’s advocate and a sheriff’s deputy visited her house and told her that her son died in jail. They told her she had to call the coroner to get the details, though, so she wasn’t sure what happened until someone in the coroner’s office confirmed it was a suicide.

Adams County Sheriff’s Office officials say they can’t yet talk about what happened at the jail because Pyle’s case is still under investigation.

If you are in crisis or are looking for mental health services for you or someone you know, call the Colorado Crisis Services hotline. Call 1-844-493-8255 or text “TALK” to 38255 to speak with a trained counselor or professional. Counselors are also available at walk-in locations or online to chat between 4 p.m. and 12 a.m.

His mother said she’s angry at the legislature and that they haven't moved to fund and prioritize mental illness. Lawmakers did vote earlier this year to spend more than a half billion dollars in federal rescue act funds on behavioral health programs.

“It’s an epidemic in Colorado and these legislators aren’t listening and (people are) committing suicide every single day,” she said. “Michael wasn’t his police record.”

Needed: More staff and more options

Throughout 2020, the Department of Human Services kept up with the evaluations for whether people were competent but scrambled to find options for them beyond the state’s mental hospital to help with restoration.

The department recently contracted with Denver Health Medical Center to provide some beds. They continue to look for more options in communities across the state.

When asked about CDPHE’s role in delaying intakes to the state’s mental hospital, an agency spokeswoman referred questions to the COVID Joint Information Center. A spokeswoman there ultimately referred questions back to the Department of Human Services.

In May, the court-appointed special masters wrote a detailed letter about all the people suffering in jails to the state Department of Public Health and the Environment, beseeching them to release some beds back for those in jail.

“Without substantial admissions to CMHIP, we foresee serious injury and/or death occurring within this population of severely, acutely ill people who have been court-ordered treatment at CMHIP,” Murrie and Gowensmith wrote in a letter to Velton Showell and Dr. Charles Howsare at CDPHE.

After that letter, which the special masters say the agency didn’t respond to, admissions into the Pueblo hospital eventually started to happen a little more quickly.

Now, however, state officials are confronting another problem: a critical labor shortage.

The Colorado Mental Health Institute of Pueblo has three shuttered units — about 70 beds total — because they can’t find enough nurses to staff them.

“We really, really unfortunately have those beds there that we can’t use,” Werthwein said. “We’re trying all different things to get staff — but it’s just such a problem. It sucks. We will try anything and everything to get these people the treatment they need.”

Werthwein said the ultimate solution is to get people charged with misdemeanors and other more minor offenses diverted out of the criminal justice system entirely and into community-based programs that can help them.

But that doesn’t appear to be happening — at least not yet.

The number of referrals for mental health evaluations in jails fell during the height of the pandemic in 2020 — but has been on a steady increase this year, which means law enforcement officers keep taking people into custody for these low level crimes, probably “because they don’t feel like they have a choice,” Werthwein said.

There were 228 referrals in January 2021 — by August that number was up above 300.