It’s sometimes said that history is a living, breathing thing, rooted in firsts and found flowering through the opportunities provided to the next generations. In the case of 2436 Gaylord Street in Denver, history is on a now-empty plot of land that once held the home of one of Colorado’s first Black doctors.

“Sadly, it's not an uncommon story these days,” said Annie Levinsky, executive director of Historic Denver, about the recent demolition of the house.

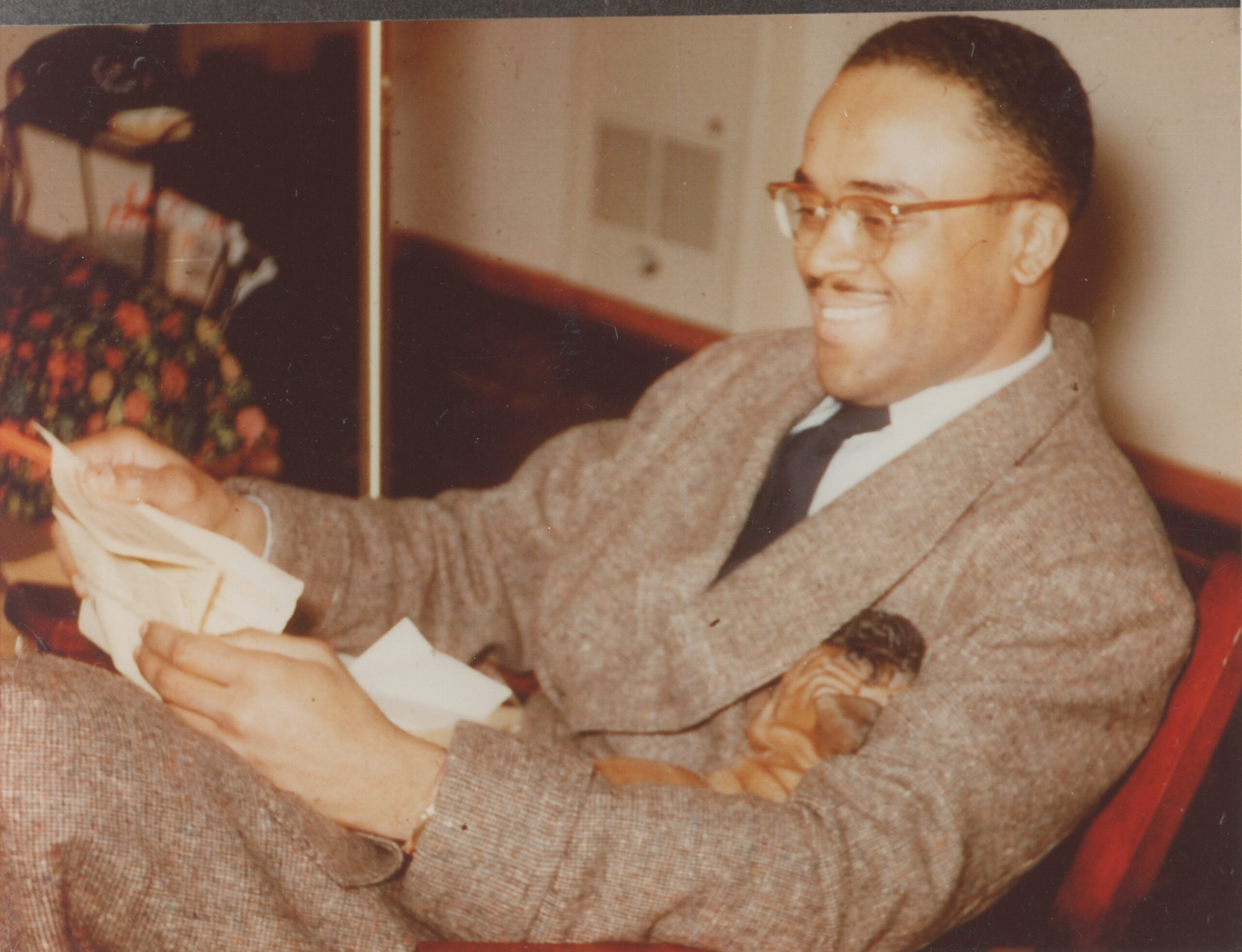

The residence, which was nestled amid a block of row houses in Denver’s Whittier neighborhood, was the home of Dr. Charles Blackwood. In 1947, Blackwood, a native of Trinidad, Colorado, became the first Black doctor to graduate from the University of Colorado School of Medicine. He eventually set up a practice in Denver and moved into the home with his wife, Vivian, and son, also named Charles.

“To me, he's like a Colorado legend who really belonged in Colorado,” said Dr. Terri Richardson, a founder of the Colorado Black Health Collective.

Dr. Blackwood’s legacy has resonated with Dr. Richardson, who started a project to help raise funds for a scholarship for medical school students of color. The Mile High Medical Society, an organization of Black healthcare professionals in the Front Range, in which Richardson serves as outreach director, recently awarded scholarships to four first-year medical students at CU, the first Blackwood Scholars.

Initially slated as one stipend, the number of recipients quadrupled after $3 million was raised, with a third of the money coming from private donations that were matched by the School of Medicine.

Richardson said the scholarship, now fully endowed, will help attract and keep more students of color at CU. As recently as 2015, fewer than two percent of the incoming class at the School of Medicine on CU’s Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora identified as Black. “There were times when there were zero Black students in the school of medicine or there was [only] one,” Richardson said.

Today, about six percent of the student population at the medical school identify as Black. While that’s roughly in line with the population throughout Colorado, Richardson said events like the pandemic have shown the importance of increasing the number of physicians of color.

“Health disparities and health inequities have been going on for decades,” she said. Studies have shown that, “if you have Black physicians caring for Black patients, then that will definitely help close some of those gaps.”

With the small percentage of Black doctors in Colorado, it has been difficult to match Black patients with Black doctors. When she retired, Dr. Richardson said her patients asked for referrals to other Black doctors in the area. “I really didn't have a lot to offer them,” she said.

“It's important for people to feel like they have someone that they can trust and someone with a lived experience that they share,” she continued. “And that is really why it's important to make sure that we are developing and creating more Black doctors here in Colorado and in the nation at large.”

A tip o’ the cap

Richardson’s research has shown a number of colleges in Colorado graduated Black doctors before Blackwood. Some, she said, worked the mining camps in Leadville during the silver boom in the 1800s.

Blackwood first attended Trinidad State Junior College, but then transferred to CU. According to a 1940 story in the Trinidad Trojan Tribune, he was “the gentleman about campus who never fails to tip his hat to a lady when he meets one on the street nor…does he fail to head the honor roll.”

For many years, Dr. Blackwood had a practice in the American Woodman building on Downing Street in Denver.

After graduating from the university, he interned at Harlem Hospital in New York, where he met Vivian. Eventually, the family returned to Colorado, where Blackwood served as a resident at the University of Colorado’s Colorado General Hospital and at Denver General Hospital.

At one point, the Blackwoods lived in an apartment at 2555 Downing Street, in a building owned by a woman named Myrtle Moore.

“She adopted him and he adopted her,” said Shirley Harris of the relationship between Blackwood and Moore. Harris, a long-time Denver resident, was friends with Moore and later became friends with Vivian Blackwood (they had children of the same age).

“I remember Dr. Blackwood’s happiness at being a father and how proud they were when “Chucky” was born and joined the family,” Harris said, referring to the younger Charles Blackwood.

Eventually the family moved into the house on Gaylord and became part of a thriving neighborhood, with Charles Blackwood opening a practice nearby in the American Woodman building.

Progress versus preservation

Earlier this year, Historic Denver launched a campaign, 50 Actions for 50 Places to celebrate its 50th anniversary. The campaign was designed to “find the next 50 places our city can’t afford to lose.” Levinsky, the executive director of Historic Denver, said the group received more than 100 nominations.

One of those nominations, from Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods, asked Historic Denver to consider the Blackwoods’ home. (American Woodman, the building that housed Dr. Blackwood’s practice, had already received landmark designation in 2009.)

“We collected those submissions through about mid-May and then we had a panel working to narrow down the list,” Levinsky said. “Just as we were working to narrow down to the top 50 — and Dr. Blackwood's house was going to be among them — we learned that it had actually been demolished the week before our deliberations.

Dr. Blackwood's home was demolished before it could be flagged for preservation.

“We've torn down more homes in Denver in the last decade than we have protected with preservation services over the last five decades,” Levinsky said.

With Colorado, and the Front Range in particular, experiencing a population boom, many old buildings are being demolished to make room for more housing. According to Levinsky, the demolitions are happening faster than preservation groups are able to act.

Unless a building has been flagged as historically significant well before it is slated for demolition, “it can be very difficult to save.”

“The timing on this one is particularly unfortunate,” continued Levinsky. “We want to welcome new folks, but we also want to feel a sense of rootedness in our community. And we want to honor people like Dr. Blackwood who were important members and contributed.”

Just as many companies and organizations have started to address systemic racism in their workplaces, the same is true in historic preservation. Groups like Historic Denver are striving to be more inclusive in the stories they tell of the city.

Historic preservation has traditionally focused on the people who designed the buildings, which hasn’t always given a complete portrayal of history.

“When we launched the 50 Actions campaign, we wanted to uncover these stories that hadn't been told or hadn't been amplified and celebrated in the same way,” Levinsky said.

“There is growing awareness, growing momentum around recognizing the places of people of color, celebrating those and amplifying the stories that haven't been told through preservation.”

Editor's note: references to race have been updated in accordance with CPR's stylebook.

Related stories

- A Respected Denver Doctor Ends Her Practice, But She’s Not Done Serving Her Community

- Dearfield Was A Booming Black Community A Century Ago. Now There’s A Renewed Push To Preserve The Ghost Town That Remains

- Denver’s Molly Brown House Was Almost Lost To Bulldozers. Now, It’s Celebrating 50 Years As A Museum

- ‘We Are Making Up For Lost Time’: Tracking Little-Known Stories Of African American, LGBTQ And Women’s Colorado History