This is part of a series by Colorado Public Radio News about housing instability in Colorado.

There’s a mobile home park in Fort Collins so old that its trees have grown tall — a community where residents stay long enough to upgrade their lots with fences, landscaping and a full slate of suburban amenities.

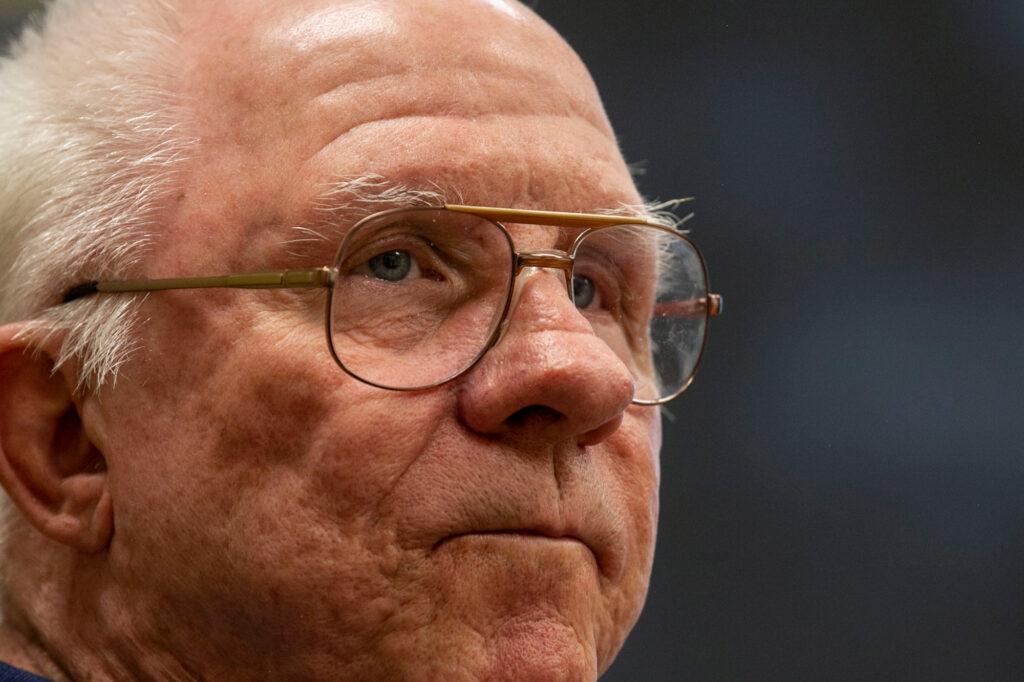

“I mean, it’s vaulted ceilings — three bedrooms, two baths. Way more than what a single old man needs, but it sure is nice,” said Bill Fulbright, 70, as he stood in the speckled sunlight outside his 1,500-square-foot home in the Hickory Village park.

On this summer afternoon, though, Fulbright wasn’t sure what would happen to his life’s investment. Like dozens of others across Colorado, the locally owned park had been put up for sale.

“Oh, I love it,” Fulbright explained. “That’s why I don't want to move. I want to stay here.”

Residents like Fulbright worried that everything was about to change — but they also had a chance to fight back, thanks to a new state law and a growing movement to empower mobile-home residents. In recent months, CPR News has tracked the progress of residents in two communities as they’ve tried to beat national investors and take control of their own communities, highlighting both successes and shortcomings.

The hundreds of residents of Hickory Village learned about the sale through paper notices posted on their doors. The white slips warned that the park was soon to be sold for more than $20 million. It was only the latest community to hit the auction block.

“We saw, this year, three mobile home parks in Larimer County ... go up for sale,” said Emily Francis, city council member and director of a local nonprofit in Fort Collins. “We haven’t seen that in a decade — and we had three within three months of each other.”

Francis has pushed to help preserve mobile home communities, saying that they’re one of the last reserves of affordable housing in the booming northern Front Range. For example, the city has passed zoning restrictions that make it more difficult to demolish and redevelop mobile-home communities.

But in recent years, Francis has seen a new phenomenon: National groups are simply buying and operating the parks themselves. Mobile homes have become an investment target because, according to one investor, they offer high rates of return with relatively few upkeep costs. These large companies argue that they can run the parks more efficiently than the historical mom-and-pop owners.

According to their critics, the new buyers often are raising rents and exploiting residents — “especially,” Francis said, “when you know that your residents don't have a lot of options, and that they'll stay there and they'll have to pay whatever rent increases.”

A movement emerges

When those sales notices appeared in Hickory Village, a countdown began. In 90 days, the sale would be a done deal. But first, residents would have a chance to make their own purchase.

Within weeks, a regional housing nonprofit, Thistle, had organized a community meeting. Soon, skepticism and confusion became enthusiasm. Fulbright recalled seeing a crowd of 200, with more than 90 percent raising their hands to support the idea of forming a cooperative and attempting to buy the park themselves.

“That made me feel like, yes, there was some value here,”he said. “When you have a community that is involved in owning, you actually do have a community instead of just a group of residents. And to me, that is highly important.”

The idea was that Hickory could become a “resident-owned community.” The concept got its modern start in New Hampshire in the 1980s and has since spread to hundreds of communities across the country, but it’s relatively new in Colorado.

Last year, state lawmakers passed a bill that was meant to support resident ownership. Under the law, park owners have to notify residents of a planned sale and allow them three months to make a counter-offer.

- He bought land in Park County before he could afford to build a home. So, he dug a hole there instead and lives in it.

- Older women experiencing homelessness in Grand Junction find a place of peace and progress

- For people sleeping in their cars, parking lots serve as a safe place to get back on their feet

- Gunnison was an affordable alternative to Crested Butte. Then came the second homes, vacation rentals and remote workers

- While tourism booms in Telluride because of its recreation and festivals, its housing market is at a crossroads

Those sales prices often can run into the millions or tens of millions of dollars — in some communities, values have doubled to $150,000 per lot, one investor said. In response, an alliance of nonprofits and investors has sprung up to help residents make their bids.

In Hickory Village, residents began by paying $25 per household to join a new cooperative that could represent them. They appointed officers, including Fulbright, who describes himself as a complete introvert.

“I'm not a sociable-type person, but I also have recognized for a lot of years that it takes leadership — it takes people who will step out there and do something,” said Fulbright, whose work has ranged from manual labor to water plant operations.

Meanwhile, the nonprofit Thistle was working to arrange financing. Under the resident-owned model, nonprofits work to arrange low-interest loans for residents. That money can come from philanthropies, but organizers also have worked for years to convince major financial institutions to make an investment that is perceived as risky.

The moment of truth

Soon, Hickory Village was ready for the next step. In another vote, members of the cooperative agreed to make an offer of $23.1 million to buy the property. To pay off the loan, residents would have to take a heavy financial hit. Over the course of five years, lot rent would increase from about $500 to about $950 per month, Fulbright said.

Fulbright believed it would be worth it. A study in New Hampshire found that, despite initial cost increases, resident-owned communities tended to settle into below-market rents — and they also became more valuable.

“They see exactly where every single dollar goes — and can control any rent increase,” said Andy Kadlec, program director for Thistle, who worked on the Hickory Village effort.

There was only one problem. The owner told them that their offer wasn’t high enough. The initial notice had omitted hundreds of thousands of dollars of additional costs.

“This got really complex,” Fulbright said. The residents had to get a lawyer involved and arrange a new offer. And as the weeks dragged on, community interest dropped. Attendance at meetings shrank, and people started spreading rumors about what the true cost to residents would be.

On the day I visited, everything was supposed to come to a head. The cooperative’s leaders were canvassing for signatures of support. That evening, they would meet at a nearby city park to see if they had enough momentum.

Fulbright held out hope all day, imagining a future for a self-governed community.

“I might need a little second job, if we buy the place,” he said as he walked the neighborhood.

But when he arrived at the site of the meeting a few hours later, the truth became obvious. There were only two people waiting: a friend of Fulbright’s and the park manager, Derald Ketels. There would be no second offer. The community organizing effort had died.

Ketels said that he wasn’t surprised, in the end, by the result: “I had my theories from the very beginning.” He thought that the rent hike had simply been too intimidating for residents that are struggling to get by.

Still, he admitted, he was disappointed. “I was hoping something would happen,” the park manager said. “I’d prefer the co-op, just because I don’t like big companies … I work for the residents, I don’t work for the owners.”

Fulbright tried not to betray his disappointment. A long, drawn-out process had allowed misinformation to spread and derailed the effort, he said. And now, he wasn’t so sure that he would stick around.

“I’d like to get somewhere where I can lock in a monthly payment. Can’t do it in Fort Collins,” he said. “I don’t have enough money saved up.”

What went wrong?

For mobile home advocates, defeats like this are common. Out of 80 Colorado communities listed for sale since the “opportunity to purchase” law took effect, only two have gone to residents.

“It’s always David versus Goliath in these situations — dealing with these venture capitalists that have a lot of cash and equity from a lot of different partners,” Kadlec said.

Uncooperative landlords can make the purchase effort especially difficult, advocates said. Kadlec and others want to see the law revised to give residents access to more information from the homeowners, including the kinds of financial documents that are made available to other buyers.

“In order for residents to be a competitive buyer … they should also have the right to any documents or resources that other buyers would have the right to access — and transparency to see the other offer on the table,” he said.

Tracey Stewart has helped to finance resident purchases as a senior program officer for the Colorado Health Foundation. She wants to see more teeth for the law, to ensure that park owners aren’t able to dodge their responsibilities under the law.

“Understanding that sellers still have the right to sell their property as they see fit, there’s still a good conversation to be had about acting in good faith and really understanding your role as the landlord, and what it means to make a move without working with the community you’re about to disrupt,” she said.

The current law says owners must “negotiate in good faith,” but does not require them to accept residents’ counter-offers. In some cases, big investors’ offers may be more favorable because they require fewer contingencies. For example, a venture capital fund might be able to skip some due-diligence inspections, while residents need to be more cautious.

In general, advocates say that it’s extremely difficult to organize a community in just a matter of months after a purchase offer. Instead, they’re seeking to make connections with residents before the next sale begins.

“Ideally, we're going into a community where we have boots on the ground,” said Andrea Chiriboga-Flor, state director of the nonprofit 9to5 Colorado.

Another way

In the high mountain city of Leadville, a counterexample is playing out this fall.

When a stranger began passing out flyers about community meetings several months ago, residents feared the worst — that their community near downtown Leadville would be sold.

“We knew that it probably wasn’t going to be good news, and we didn’t want to know about the bad things that were coming,” said Cesiah Santillan, 37, speaking through an interpreter.

In fact, the park’s owner did want to sell — but he wanted to sell to the residents.

“I guess I’m a little unique in our situation,” said Matthew Bransfield, who bought the park in 2019 for $1 million with the backing of his small Denver-based investment group.

He originally intended to buy more parks, in addition to another that he co-owns in Empire, but competition with major investors slowed that plan. Instead, he found himself increasingly drawn to the resident-owned model.

“It just feels like something good that we can do inside of the community and inside of an asset class, that's been in many cases historically predatory upon the end tenant,” said Bransfield, who could still profit on the sale.

After the owner contacted housing organizers, Thistle and the local nonprofit Lake County Build A Generation helped residents learn about the deal and navigate the purchasing process.

With extra time — and a cooperative property owner — enthusiasm has grown strong among the park’s 30-odd households. Several of the park’s residents said they want to preserve some of Leadville’s last accessible, affordable housing. The park stands within walking distance of the city’s historic main street, and it stands just across the street from a half-built development where homes are selling for well over $500,000.

“We can pass this along to the youth … even if you can’t afford the land individually, this community will still be preserved as a mobile home community,” said Esther Soto, president of the newly formed neighborhood cooperative, through an interpreter.

The prospect of self-ownership has changed how some residents are thinking about the future.

If the sale happens, “we won’t ever have to worry again about, ‘What if they sell it again? What if they put it up for sale? What if we have to move?’ We won’t ever have to worry about that,” said Josefina Chairez, 50, a housekeeping supervisor for a local hotel, through an interpreter.

In their home at the park’s edge, Santillan and her husband are building for that future. They had postponed a list of home projects for years, fearing they’d be forced to move. But in recent months they’ve been replacing floors, doors and popcorn ceilings — with growing hope that they’ll be here for the long run.

“That’s when we really decided to do more work on our home,” she said.