Once sleepy affairs, school board elections across Colorado are now zealously contested over issues of COVID masking in schools and teaching race issues in classrooms. What did that mean for this year’s elections?

On Tuesday night’s races, one analyst said “it wasn’t some conservative backlash statewide” while another contended that it was a “tremendous victory for the rise of parent power.”

A press release from the Colorado Republican Party touted the school districts that “WE NOW CONTROL” (emphasis theirs) while a release from the state’s largest teacher’s union declared the election a big win where voters “stood with educators” in many high-profile races.

However you look at it, and from whatever side of the political spectrum you’re on, one thing is certain: This year twice as many candidates ran for school boards across the state compared to 2019.

Why the high interest? A turbulent pandemic school year stoked anger in many parents — about closed schools, mask mandates and what they believe is being taught in classrooms. That fueled turnout at school board meetings, which in turn laid the groundwork for an election that saw millions of dollars in dark money, parent Facebook groups, and endorsements from political parties in the traditionally nonpartisan races.

Overall, candidates backed by teachers’ associations won in many large districts — Denver, Jefferson County, Cherry Creek, Durango and the Poudre School District in the Fort Collins area — while candidates backed by conservative groups ousted incumbents in several Colorado Springs districts, Douglas County, the Greeley Evans School District 6, as well as some smaller districts.

The biggest board turnover was in Douglas County, where dark money interests, which don’t have to disclose who funded them, flowed in.

A conservative slate of candidates won big in Douglas County on Tuesday night, ejecting two incumbents, and installing a new board majority that promises to give parents a place at the education table. The race was one of Colorado’s most contentious and hard-fought, after a year of heated public comment periods during school board meetings.

The Kids First slate of Mike Peterson, Becky Myers, Christy Williams and Kaylee Winegar soundly defeated incumbents Kevin Leung and Krista Holtzmann, along with hopefuls Juli Watkins and Ruby Martinez.

The winning slate’s campaign manager Holly Osborne said the goal was to bring some balance back to the school board “where all seven minds didn’t think alike.” She stressed that while the slate of elected candidates is conservative, they are moderate conservatives.

“They don't want to run over anyone with ultra-conservative ideas. They truly want all sides to work together for kids first.”

DougCo’s district politics have been fiery going back years when a school board majority with a “reform” agenda ushered in a now-defunct voucher program and an unpopular performance-based teacher pay plan. Nearly eighteen percent of teachers left the district in 2014. A 2017 election flipped the board majority to one that increased teacher compensation, quelled the turnover and helped pass the first property tax increase in 12 years. That new money helped pay for more student mental health support.

Teachers are worried the new slate could bring another whiplash akin to the teacher exodus the district saw last decade, according to Kevin DiPasquale, president of the Douglas County Federation, a local affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers — a union.

“People are worried that this similar work environment will be brought back and impact their ability to teach and do what's best in the classroom,'' he said. “The mood of educators today ranges from deflated to devastated. Teachers are torn between their profession, their community, and the schools, which their own children attend … They're very sad.”

He said many teachers believed the board of the past few years had their backs.

“They didn't have to worry and look over their shoulder wondering if someone was going to contradict their expertise,” DiPasquale said.

The new conservative board majority, however, said in forums that they want to focus on teacher retention, don’t support school vouchers and all four stated they support asking voters for another property tax increase to boost teacher’s wages closer to that for teachers in surrounding districts. Osborne said a lack of public trust in the current board would have made it difficult to pass a new tax increase.

The new board majority “feel that they can reach out to those people who might have otherwise voted against it and actually build that trust with them,” said Osborne, the campaign manager.

What more “parental control” looks like in schools is unclear at this point. The rhetoric around masks and doubts about the district’s equity policy — which, among other things, calls for establishing a system for identifying racist practices and discriminatory behaviors — surfaced in school board forums.

“I think they do want to take a good, hard look at the equity policy,” Osborne said. “They think on paper that it's actually very good. They would just like to examine the implementation of that policy and make sure that we're doing it really well.”

DiPasquale hopes the new board will include teachers in discussions on any changes to district policies.

“I'm hopeful that the new board members stay true to their campaign promises of listening to teachers and staff and supporting them with what they need in the classroom.” Incumbent Krista Holtzmann, who lost her re-election bid, believes that national political conversations that entered school board rooms took the spotlight away from children.

She said not a single family has been able to point to where “critical race theory” is happening in classrooms. She maintains the COVID mitigation strategies kept DougCO schools in person earlier than any other Denver Metro district. But she said, she has to hope for the best.

“I wish them success and really putting kids first, rather than prioritizing political agendas espoused by those that have endorsed their campaigns.”

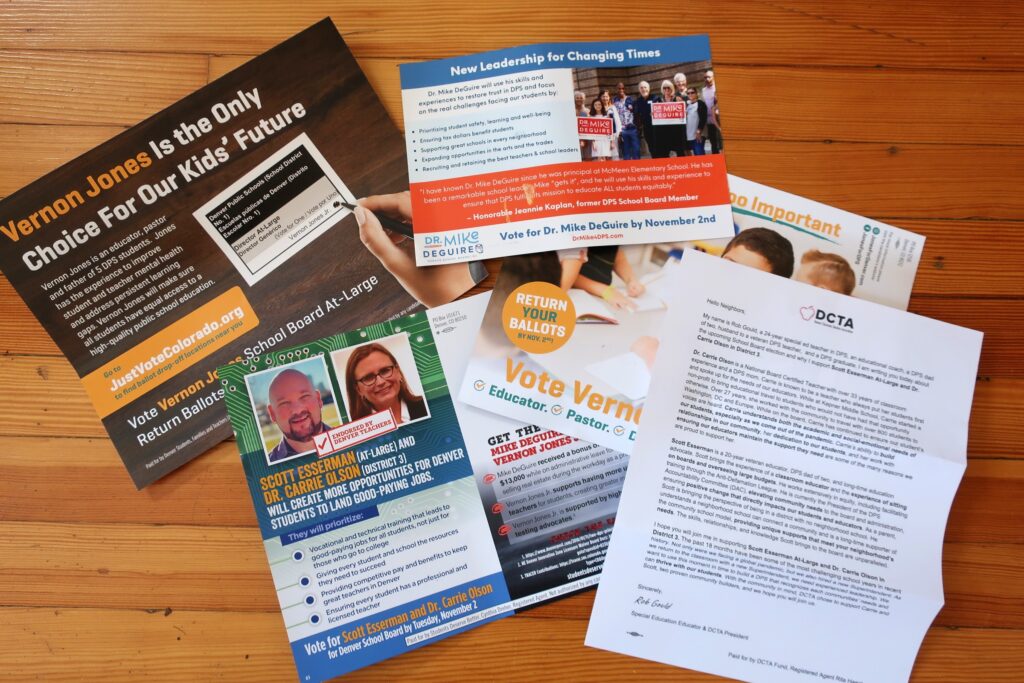

Candidates backed by teachers prevailed in many major districts — from Jefferson County and Fort Collins to Durango and Steamboat Springs. But Denver was the biggest.

Incumbent Denver Public Schools Board President Carrie Olson and candidates Scott Esserman, Michelle Quattlebaum and Xochitl "Sochi'' Gaytan won, though Gaytan and Quattlebaum’s leads are far smaller than the others and outcomes in them may still change.

Those four candidates were backed financially by the Denver Classroom Teachers Association — a DPS teachers union — while independent expenditure committees pumped money largely into their opponent’s campaigns.

Denver, up until 2019, had a school board that oversaw an aggressive plan to open up charter schools, close low-performing schools, and grade schools heavily on test score performance. The actions tended to divide the community into pro-charter and anti-charter camps. But lines are blurrier now. And with so many challenging issues facing the district, it is difficult to gauge how much “dismantling of the reforms” a new board will pursue, said Parker Baxter, director of the Center for Education Policy Analysis at the University of Colorado Denver.

The fact remains that DPS has 58 charter schools, which operate independently, 50 innovation schools that follow different rules than traditional schools, and has 50 schools housing both charter and traditional schools in the same building.

“Denver will be even more complex (for a new board) because of this governance and structural issues that are still going to be in play. I think we can expect more conflict, rather than cooperation, somewhat ironically … maybe,” Baxter said.

The board will also oversee a new superintendent, who was selected partly to unify the district, oversee the creation of a new strategic plan, and make decisions on whether to close small schools as district enrollment declines.

“There will be a lot of pressure on the new board to not do so,” Baxter said. “And yet the financial condition of the district seems to indicate that some action is required.”

Krista Spurgin, executive director of the nonprofit Stand for Children, hopes the board listens to what the community wants and digs into successes and collaborations, whatever the school model.

“For me, the hope is that this new board, whomever it ends up being, really leans in to understanding what has worked over the years versus just, ‘What do we need to get rid of?’”

Aurora schools will also grapple with some similar challenges. It has declining enrollment on its west side but new development means future new schools on the east side. Four new school board members will also have to decide how much of a role charter schools will play. Candidates backed by teacher’s associations won their races, though a charter school teacher, who was backed by reform groups, was also elected.

Jefferson County, the second-largest district in Colorado, saw a contentious race for three school board seats on a five-member board.

Mary Parker, Danielle Varda, and Paula Reed, the slate endorsed by district teachers and many community members, won easily in Jefferson County, beating out a more conservative slate of candidates.

They say a top concern will be recruiting and retaining staff. Like other districts, Jefferson County has had to cancel bus routes and rely on pre-packaged lunches in some schools because of staff shortages. Other issues they’d like to pursue are boosting career and technical education and addressing the youth mental health crisis.

Their opponents, who were endorsed by the Jefferson County GOP, weren’t an official slate but were supported by JeffCo Kids First, which was involved in organizing mask protests. Some of those candidates spoke in forums about the need for better financial stewardship of district resources and criticized the district’s COVID mitigation strategy.

“Hundreds of educators, parents, and community members were determined to support the candidates who are committed to focusing the district on providing a high-quality education to every Jeffco student regardless of neighborhood, race, religion or income,” said Jefferson County Education Association President and art teacher Brooke Williams. The head of the teachers union there said the results send a clear message that the community supports strong neighborhood schools.

In the Cherry Creek district, incumbent Kelly Bates and Kristin Allan, both backed by the district’s teacher association, won. Sarah Hurianek, who was endorsed by the St. Vrain Valley Education Association, won a seat, beating Natalie Abshier, who regularly spoke against the district’s mask policy and “critical race theory” during public comment at school board meetings. The other two open seats just had one candidate.

Parent surge fuels victories in other parts of the state — Colorado Springs, Greeley and Mesa County

Alongside Douglas County, candidates who billed themselves as conservatives or supporting “parents’ rights” flipped the boards in Colorado Springs D11, Falcon 49 district, and the Greeley Evans School District 6.

“D11 has been a fight for 20 years between reformers and the unions, and the fact that reform-minded parents won a sweeping victory there — have a five-two majority — that's enormous,” said Tyler Sandberg, vice-president of the conservative education group Ready Colorado.

The organization’s campaign arm spent $30,000 on races in Douglas County and Aurora.

In the Academy 20 school district race in El Paso County, three candidates opposed to masks, and who were supported by an independent expenditure committee with Republican ties, won. The three spoke out against teaching “critical race theory,” and some declared students should not be “indoctrinated.”

Other conservative candidates, some ardent opponents of masks and proponents of “family values” won in other Colorado Springs-area districts.

In Greeley Evans School District 6, incumbent Michael Mathews was re-elected, but three elected newcomers say the district can do better. Two of them told the Greeley Tribune they were inspired to run after seeing what their children were learning in school during the pandemic. One, a former teacher, said she thinks the “social and emotional stuff” should be taught at home and schools should focus on core subjects.

Three new candidates backed by the local GOP and several conservative groups won in Mesa Valley School District 51. The groups focused on parents’ rights and “patriotism and pride in American history” and opposed “critical race theory.” A four-person slate who billed themselves as “conservatives” and spoke in part of the need for more parent input, ousted incumbents in Woodland Park.

Ready Colorado’s Sandberg attributes election results to school closures.

“Overly and unnecessarily long school closures created a wave of frustration of parents who were no longer willing to just trust the system,” he said. “The system failed their kids and failed their families, and they were willing to vote in large numbers across the state for a non-traditional candidate.”

Sandberg said while “critical race theory” might inaccurately describe what is being taught to children about race in schools, he believes a “woke, progressive” agenda has infiltrated the teacher corps.

“Parents for the first time were sitting there at the kitchen table next to their kid who was in Zoom school and they're saying, ‘My kid is behind in math and reading, and instead they were focusing on this political propaganda, really?”

He said parents simply want more transparency about what is being taught, not the opaqueness they experienced before the pandemic. And it’s not just how history is taught. Sandberg said parents are asking questions about how reading is taught (such as, does it serve students with dyslexia), the rigor of instruction for underserved students, and whether a particular school’s approach fits their child’s learning style.

“Parents learned more about their kid's learning style in the last 18 months than they ever have in American history,” he said, “because they were teaching their kids and they're watching them struggle or succeed.”

Sandberg said he’d like school boards now to focus on how to improve graduation and literacy rates, how to ensure that kids don’t need remedial classes if they go to college. Amie Baca Oehlert, president of the Colorado Education Association, agrees and says that’s been the focus of teachers all along. She said divisive national political issues like mask mandates have taken a toll on educators across the state.

“Our educators are tired. They’re stressed out. It's difficult to educate students in the midst of an ongoing global pandemic, but when you also have these very big political and social pressures entering into the work, it certainly creates challenges.”

She said teachers are looking forward to working with new school boards.

“Our hope is that when you get elected to a school board, it is not just about one or two issues. It is about a multitude of issues that impact educators, students, and the community at large,” she said. “And so, we're hopeful that they will focus on that broad swath of issues and not just on these very hyper divisive political issues that many of them ran on.”