This is part of a series by Colorado Public Radio News about housing instability in Colorado.

Rosie Rutherford can’t remember the last time she felt safe in a homeless shelter.

Since July, the 53-year-old has lived for free inside a quiet, two-bedroom apartment in Greeley. The place is sparsely furnished, but the kitchen is stocked with food. She watches DVDs most nights on a small, donated television.

“This place is one of the very nicest places I’ve ever been as a homeless person,” Rutherford said. “And I’ve been in a lot.”

But it won’t be around for much longer.

The emergency shelter, set up in response to the pandemic, is shutting down next month. The United Way of Weld County, which manages the facility, points to a dwindling supply of pandemic relief funds.

Many residents, including Rutherford, are now struggling to find a place to live as they confront familiar barriers such as rising rents and limited supply in the region’s housing market. Some worry they’ll end up back out on the street.

Rutherford calls the closure a bad move. The Air Force veteran suffers from lupus, anxiety, depression and other health conditions that make it difficult to work. She relies on several hundred dollars in disability each month to get by — and it doesn’t cover what one-bedroom apartments are renting for in Greeley and along the Front Range.

“I sure hope they have something better out there for people,” Rutherford said. “Why on earth would you close down the only thing that’s working?”

‘It hurts to see it close'

During the spring of 2020, amid Colorado’s first COVID-19 wave, Greeley city leaders started looking for space to build a hospital overflow center. They found a spot inside a light blue, three-story nursing home on the Good Samaritan Society’s Bonell Senior Living Campus.

The building sat unused and in disrepair for years before the pandemic. But it had several dozen apartments, office space and security infrastructure, which made it a good candidate.

The city renovated the space using money from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act — known as CARES. But hospitals absorbed the surge in patients that summer, and the renovated overflow space wasn’t used.

Then last fall, the city asked the United Way of Weld County to take over the facility. The charity had been looking for an alternative to its crowded indoor winter shelters to help homeless residents find a place to social distance.

It opened the emergency shelter last November.

Since then, the charity has housed roughly 100 people at Bonell. The majority of residents are older than 50. Most have pre-existing health conditions that make them particularly vulnerable to COVID-19.

Residents each get their own one- or two-bedroom apartments. Masks are required in common areas. The building also has 24/7 security and on-site case managers—all features designed to reduce the spread of COVID-19 among an at-risk population.

And the numbers show that it works: The shelter has recorded eight total COVID cases since opening. It hasn’t had any major outbreaks or deaths due to the disease, according to staff counts.

Meanwhile, more traditional homeless shelters have struggled with large outbreaks. One shelter in Fort Collins, where residents sleep side-by-side in large groups, has logged more than 100 cases among visitors and staff in the past year.

Some residents at Bonell have gone on to other housing programs throughout the region. Others have left the shelter on their own terms. About 40 people still live there.

“It hurts to see it close,” said Jayme Schledewitz, the shelter’s manager. “I want to see everyone do well and be housed. I consider the guests like my family.”

United Way tried to find more COVID relief funding to keep the shelter going through the winter, according to Schledewitz and other staff. But initial sources have all been tapped out, they said.

Now, staff have pivoted to helping residents land on their feet once the shelter closes. Housing navigators are on site most days, meeting with residents. But they haven’t found a place for everyone to go.

Many residents face multiple barriers that make it more difficult to find stable housing, including personal criminal history, a high cost of living and poor credit history, Schledewitz said.

“Honestly, I see about half of the guests going somewhere,” she said. “We do have some that I feel will end up back at our cold-weather shelter.”

‘These people really care about us’

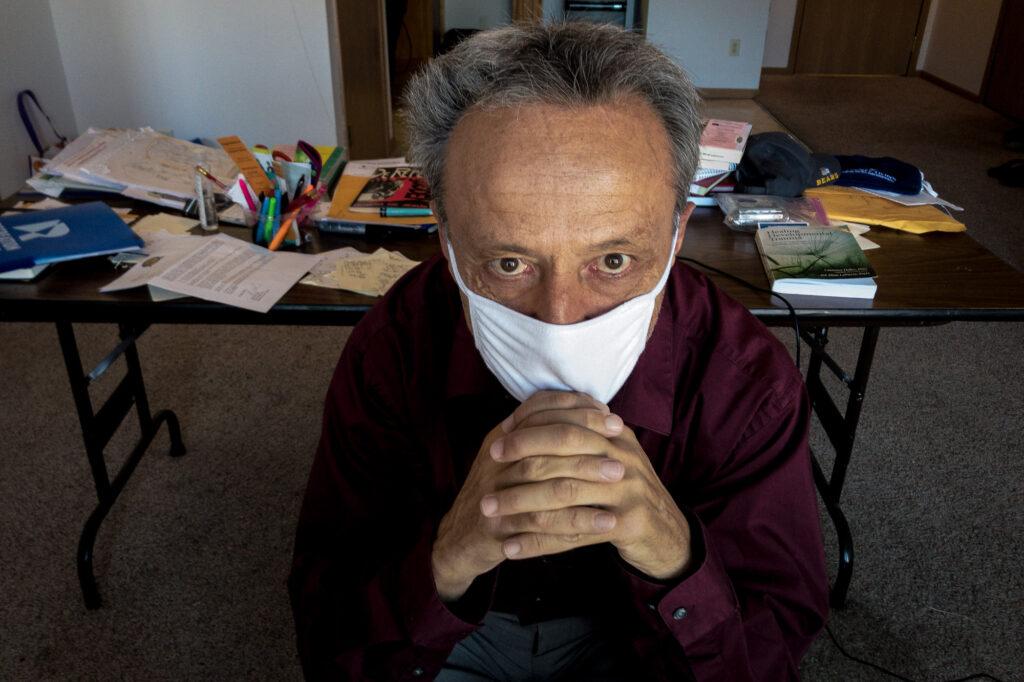

Frank Afflitto, 62, is a former history professor and author who became disabled, then homeless several years ago.

When the pandemic started, he tried to avoid sleeping in homeless shelters because of overcrowding. He opted to camp outside near a local Wal-Mart, he said.

Since moving into an apartment in Bonell this past summer, he’s felt like his life has turned a corner for the better, he said. He’s started seeing a therapist and writing a book on war crimes.

Afflitto lights up while talking about a folding table he uses as his desk in the middle of his living room.

“I feel like I’m in a very good place here and in the community,” said Afflitto, whose only monthly income comes through Colorado’s Old Age Pension.

On his messy desk, Afflitto picks up an application for a Section 8 housing voucher. Bonell shelter staff have supported him as he works to find housing through the program, he said.

“I have a team that backs me,” Afflitto said. “I’m not in a warehouse, I’m not on a conveyor belt. These people really care about us.”

Inside the shelter’s small front office, Angelica Perez-Swiler, a United Way housing navigator, spends most days looking for housing options for the residents, scrolling through Facebook ads, Craigslist and countless other websites.

Rents in most Colorado cities dipped last year, but are now back at record highs. The going rate in Greeley is about $1,100 for a one-bedroom, according to Zumper, an apartment search website.

“It’s crazy,” Perez-Swiler said. “Finding the cheaper ones has been like a miracle.”

She’s found places for some residents by matching people with roommates, so their rent is less, she said. Others, like Afflitto, are applying to government-assisted housing programs.

But Perez-Swiler worries about finding options for everyone.

“I do think a lot of our residents will be housed [by December],” she said. “There are options. But I do think we're running low on time. So it’s high-stress.”

‘The takeaway is that this works’

United Way plans to keep the shelter running at full capacity through its final day on Dec. 31.

After she told residents about the closure, Schledewitz, the facility’s manager, looked for ways to lift everyone’s spirits. She bought dozens of colorful post-it notes, construction paper and designed a big billboard in the shelter’s main lobby.

She asked staff and residents to write positive messages on it.

While walking past the billboard in the shelter’s main lobby on a recent afternoon, she pointed out several notes that stuck out to her.

One simply said, “It’ll be okay.”

Schledewitz said she hopes that the community can learn lessons from Bonell’s time being open, especially as COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations climb in the state.

“The takeaway is that this works,” she said. “People that have been on the streets for so long are no longer on the streets. They have a place to go at night.”

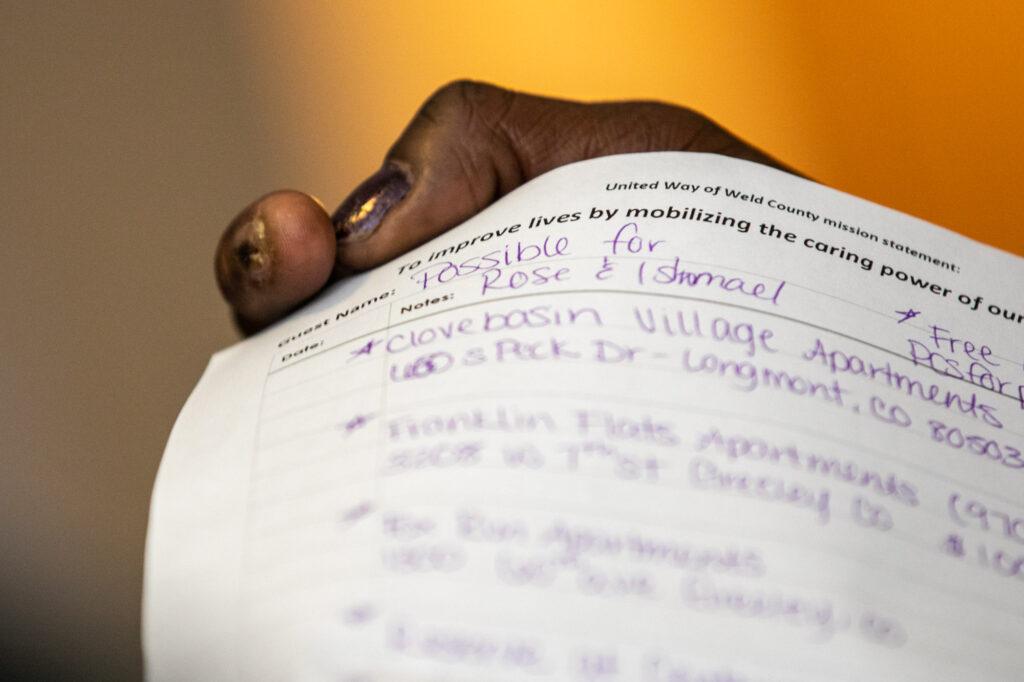

Rutherford, the 53-year-old Air Force veteran, keeps a list of low-income apartments across Colorado on her kitchen counter. She’s called several times in recent weeks to inquire about renting a place, but hasn’t had any luck yet.

She’s nervous about her next steps but hopeful. She prays each day that she finds a new home, she said.

“I know that somebody is out there looking for people like me that are just trying to get their lives back together,” Rutherford said.

For now, she waits for a call back.

- Inside two Colorado mobile-home communities fighting to avoid corporate takeovers — with very different results

- He bought land in Park County before he could afford to build a home. So, he dug a hole there instead and lives in it.

- Older women experiencing homelessness in Grand Junction find a place of peace and progress

- For people sleeping in their cars, parking lots serve as a safe place to get back on their feet