May 6, 2021, turned out to be a fateful day for Colorado.

On that date, a coronavirus variant first identified in India was discovered in Colorado for the first time. Five cases of the B1617.2 strain were identified in Mesa County. None of those people had a recent travel history.

It was the delta variant.

Now it makes up 100 percent of all COVID-19 cases in Colorado as the pandemic rages on, with transmission, cases, hospitalizations and deaths steadily marching upward.

The latest projections show Colorado’s situation has grown so dire, hospital capacity could be breached in the coming weeks.

Why now? What’s driving it?

The short answer is that no one knows. But there are a lot of guesses.

Colorado has shown that a 62 percent vaccination rate is not enough.

Lots of states have vaccination rates lower than Colorado, and for now, at least, seem to have transmission under better control.

Lots of states have populations who are even less likely to wear masks or practice social distancing than Coloradans, yet they also currently have lower case rates than the Centennial state.

But Colorado, along with several other states in the Rocky Mountain West enduring outbreaks, has both, experts note. Though Gov. Jared Polis and state public health officials have touted Colorado’s vaccination rate (in the top 20 among states, according to the New York Times tracker), with 62 percent of residents 12 and older fully immunized, it’s still just not enough.

Millions are not immunized, either through choice or ineligibility. And there are enough pockets of extreme indifference to COVID-19 to create a lethal stew that experts theorize has allowed the virus to spread and persist when it was forced to, at least for now, retreat in some other places.

“To me, all of this points towards the sort of tragic collapse of the non-pharmaceutical interventions that we know work to control (the coronavirus),” said Samuel Scarpino, a complex systems scientist and the Managing Director of Pathogen Surveillance at The Rockefeller Foundation.

That coincided, “with the return of cooler weather, which makes ventilation harder.”

Some other states have colder weather, and it’s been a mild fall in Colorado.

Whatever the reason, the state’s situation is perilous, with “a rising number of cases before the holidays,” said Dr. John Swartzberg, a clinical professor emeritus and expert in infectious diseases at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health. “Because the holidays aren't going to make it better.”

Polis ended many emergency health orders this summer. Months later, the situation is dire.

Another date stands out in Colorado’s pandemic story this year: July 8. That’s when Gov. Jared Polis ended the remaining health emergency executive orders that guided the state since the early days of the pandemic.

The state had reached 70 percent of the eligible population vaccinated with at least one dose when Polis rescinded all remaining executive orders related to COVID-19. He signed a new “Recovery Executive Order” focused on returning the state to normal. Though he retained some authority through executive actions, it was a signal the state was ready to move on from COVID-19.

It was a gamble.

At the time, the pandemic seemed manageable, but the virus was not gone. Colorado had 284 patients hospitalized with confirmed cases, a rate of positive tests below three percent and a case rate of about eight per 100,000 people.

Now it has five times as many hospitalized COVID-19 patients, the positivity rate has more than tripled, and the case rate is seven times greater.

As the pandemic has exploded among the unvaccinated in Colorado, the governor and top leaders have consistently pushed residents to get vaccinated, most recently for the 5-11 age group.

On Thursday, the governor signed an executive order opening up booster shots for anyone older than 18, beyond what federal agencies have authorized so far.

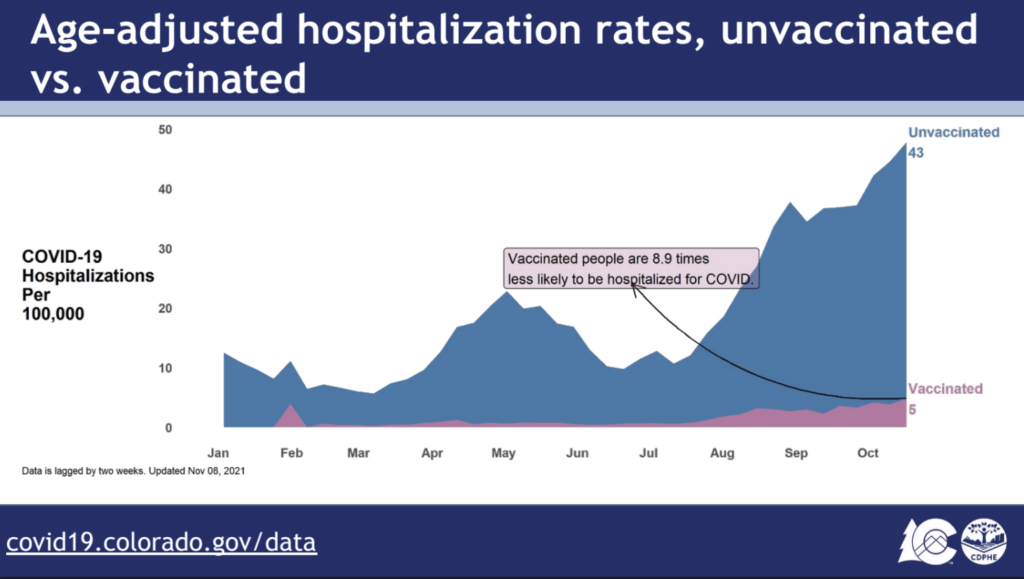

Though 62 percent of Coloradans are fully vaccinated, and another 637,000 now have gotten a third dose, that still leaves some two million unvaccinated. They make up 80 percent of those hospitalized and account for far more deaths than vaccinated Coloradans.

And what Polis and his team have resisted are many of the non-vaccine measures seen earlier in the pandemic. There’s been no return to statewide measures Colorado adopted earlier in the crisis, like a mask mandate or restrictions on indoor gatherings. Many local public health leaders have followed that lead.

“You can just draw a straight line in Colorado in terms of the slope has been going up pretty consistently since July,” said Swartzberg.

Nuggets and Avs games: A case study in crowds at Ball Arena

A look at how big crowds have been handled is instructive.

Fans returned to Ball Arena, home to the Denver Nuggets and Colorado Avalanche last month, at full capacity of more than 18,000. At first, proof of vaccination or a negative test was not required. Masks were strongly encouraged, but few were seen in the crowd.

In the winter and spring, the teams played before reduced capacity crowds of fewer than 5,000, while the state health department worked to limit spread as vaccines were being given to a growing share of the population. Mask requirements were enforced, with Ball Arena ushers serving as mask proctors to be sure exceptions for eating and drinking were the only ones made.

In May, capacity was expanded to 7,750, a cautious move to gradually let more people cheer through the playoffs while still enforcing masks and social distancing. At the time, the state was recording about 5,437 COVID-19 cases a week.

In mid-October, as fans streamed into the arena with no capacity restrictions, the state recorded 13,714 cases.

With no statewide rule in effect, the city left it up to the individual businesses.

By the end of last month, with Colorado’s coronavirus curve still shooting upwards, Ball Arena reversed course, after consulting with local, state and federal authorities. Its owner announced those attending games at the venue (or concerts at either that facility or Denver’s Paramount Theatre) would need to provide proof of COVID-19 vaccination or of a negative test taken within three days of their event. That rule went into effect Wednesday.

But, for now, there’s no capacity limit.

On Wednesday, Polis told his advisors on the state’s emergency epidemic response committee he was looking to private venues and local communities to tighten restrictions on indoor gatherings. “We need to make indoor events safer. We can't afford super spreader events,” Polis told the group, though he did not call for statewide measures.

For months, Polis has talked about hospital capacity steering his decision-making.

The governor was asked by reporters in August if a statewide mask mandate was in the cards, with the return to school happening.

“We are not at capacity,” he said “We don't wait till we're overwhelming our hospitals. We watch the trend and we act before we overwhelm our hospitals.”

Young people make up the majority of COVID cases, but older Coloradans are more likely to be hospitalized and to die.

The fuel for the fire is still coming in large part from younger Coloradans. The bulk of the cases throughout the pandemic have been in those under 40, while the worst impacts of the virus, in hospitalizations and deaths, have been in older Coloradans.

“The Delta strain spreads through children, through schools and into families. And we are seeing that. Families are being affected now from children bringing it home,” said Dr. Eric Simoes, an infectious disease expert at Children’s Hospital Colorado, at a press conference this week.

That’s one reason why the state is pushing so hard to vaccinate kids. While younger people make up the majority of cases, most hospitalized COVID-19 patients are over 60.

State epidemiologist Dr. Rachel Herlihy said that’s in part because of signs the original vaccines are wearing off, especially in older adults. And she said that highlights the value of boosters in “really bringing those immunity levels back up and protecting our most vulnerable individuals.”

Still, despite the state aiming to get more vaccination, and now booster shots in arms, the numbers of unvaccinated are still too high to bring Colorado’s pandemic curve under control.

“It's gotta be these pockets of unvaccinated individuals interacting and allowing the virus to still spread. That would be my best guess,” said Jude Bayham, an assistant professor at Colorado State University with the state’s COVID-19 modeling team.

His work spotlights that people are socializing more. It's showing up in the data.

“Since about early September, we've essentially been back to pre-pandemic levels of mobility,” he said.

The vaccination rate is different county-to-county.

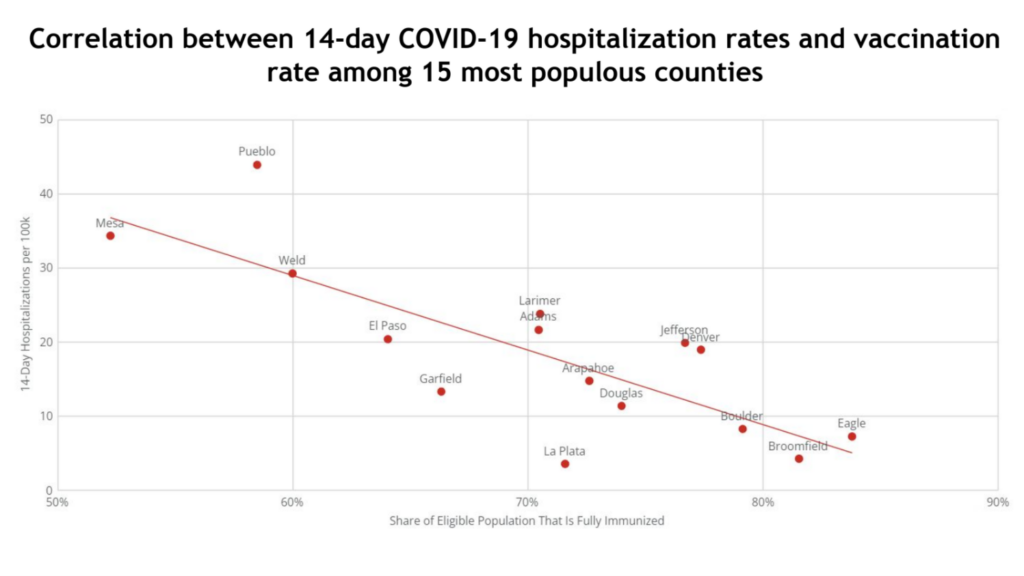

The surge has hit counties with lower vaccination rates hard, causing more hospitalizations per capita than those with higher rates.

Polis said counties, like Eagle, Boulder and Broomfield, with vaccination rates into 80 percent and above, are faring better.

“You get around 80, it really shows there’s an inception point. When you get to about 80 percent per protected, there is a significant herd immunity impact, and your hospitalizations go down several times,” he said.

But those on the other end of a chart the governor and health officials often share are counties like Weld, El Paso, and Mesa. There, relatively low vaccination is powering high levels of coronavirus hospitalizations.

For months, health research groups like KKF have noted a sharp and growing red-blue divide in vaccination rates. Counties that voted for Trump in the 2020 Presidential election are less vaccinated compared to those that voted for Biden.

In Colorado, vaccinated people are 8.9 times less likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19 than those who are unvaccinated, according to the health department.

In Pueblo County, one of Colorado’s most purple counties, hospitals are jammed with COVID-19 patients. About two-thirds of the county’s eligible population has been vaccinated with one dose. And public health officials say residents have eased up on other measures.

“We as a community, became a little lax in terms of our physical distancing, maybe our hand-washing and respiratory etiquette, as well as wearing masks,” said Dr. Chris Urbina, medical director for Pueblo’s health department.

How can Colorado improve its COVID situation?

So how does Colorado change course — and start to bring the spread of the virus back down?

The Rockefeller Foundation's Samuel Scarpino said to rein in the current ominous spike it will take vaccines, yes, but also a return to the COVID containment playbook.

“We know how to control (the virus). It's masking, testing, and then case investigation, tracing, isolation, quarantine. Now we have vaccines,” he said.

But he says it’s important to alert the public that things are now bad. And it’s a hard thing to do when mixing in crowded indoor places is fully permitted as if the pandemic hadn’t happened and isn’t still here.

“The ‘sending the signal to the public’ thing is really important,” he said.

That’s why he applauds vaccine requirement measures like Ball Arena is now requiring. It helps in “really communicating to the public that things are risky,” and vaccination is a way to protect yourself.

- Nov. 10: Colorado could exceed hospital capacity in December as Polis pushes boosters, but no mask mandate in sight

- Nov. 8: With Colorado hospitals full and short-staffed, some health care providers may need to work in roles they aren’t certified for

- Nov. 3: With Colorado hospitals overwhelmed, patients can now be transferred anywhere in the state

- Nov. 1: New Colorado health order allows hospitals to refuse patients as COVID cases and hospitalizations rise

- Oct. 25: Colorado COVID-19 hospitalizations keep rising, with unvaccinated patients filling ICUs and acute care wards

- Oct. 22: ‘No place for the patient to go ’ — As a new COVID wave hits, hospitals struggle to find open beds

- Oct. 12: Hospitalizations and deaths climb as Colorado’s fifth COVID wave keeps rising