He didn’t feel safe, so the 14-year-old boy brought a knife to his middle school in Aurora.

And he got caught.

“People don't act right in school. They don't have any morals or respect,” he said. “And then we come across a person like me who has respect and morals for other people. They don't like it. So, they don't like me for no reason. So I'm kind of a target.”

The teen, who CPR News is not identifying, said he likes to fight and has tried to change.

“I feel like I'm slipping now. I'm slowly becoming what they so-call a menace to society.”

He was at Denver’s Carla Madison Recreation on Saturday seeking what he called “guidance.” He was one of 20 other Black youths who came together for a Youth Gun Violence Awareness and Suicide Prevention Wellness weekend.

The youth, especially the young Black men in the organization, said they don’t feel seen, heard or valued and it plays out in what many experience as teenagers — a cycle of poverty, despair and drugs. Saturday’s event was meant to give the group a sense of self-awareness and teach them skills and techniques to cope with unresolved trauma and other feelings like anger, sadness and anxiety that lead to violence and suicide.

“I will let my hope, not my hurt, drive my future,” Halim Ali said at the beginning of the Saturday session.

Ali is founder of the nonprofit From The Heart Enterprises, which hosted the event along with the other members of the King’s Council’s Black Male Health Initiative — The Crowley Foundation and Apprentice of Peace Youth Organization. The session was planned months ago but it comes on the heels of a spike in youth violence in Aurora, where 16 young people were shot in various incidents last month.

Some youth at Saturday’s event have been involved in fighting in schools or other disruptive behavior; others were just interested in attending with their friends — or their parents or schools referred them.

‘They don’t know how to deal with emotion’

Facilitators at the event said many kids really don’t know who they are. “A lot of our youth, they're not in tune with themselves,” said facilitator Dominique Lawrence, 29. “They don't know how to deal with emotion. They don't know how to deal with heartbreak, frustration, anger.”

Lawrence started his own journey two years ago. He was in a dark place, he said, depressed, stressed and always sick. No one at home had taught him how to process emotions so he started studying and exploring himself.

“How do I feel when I get angry? How do I feel when I'm sad? What do I do? What are the things, how do I react? And I'm really just meditating and building and cultivating thoughts and ideas and practice on how to combat and deal with those different emotions.”

Ali focused on that while kicking off the session: Why do men have trouble asking for help. Some of the participants said it makes them feel like less than a man, or they fear judgement, burdening others, or wounding their pride and ego. One 14-year-old said he doesn’t trust most people.

Ali encouraged the attendees to be vulnerable during the breakout sessions, led by facilitators like Lawrence, some of whom in the past had been involved in gangs, drugs and violence.

“I’m still learning how to be a person,” said Andre Coleman, 16, who has found mentorship with From the Heart for the past five or six years. He said he’s learned Tai Chi.

“It just helped me so much. I used to fight all the time. And then after that I learned how to calm down and use my body to let it flow, let my breath flow," Coleman said. “I'm still learning (about) my temper, but I learned how to control it.”

Dealing with anger, pain

An overarching theme of the day was how to release negative or toxic emotions like anger, sadness and frustration, and how to shift how one feels about someone you feel has done you wrong.

“You have trusted people in this room you can count on,” Ali said.

The group unpacked why anger is so omnipresent in young men. Several talked about fathers who weren’t there, men in the family who mentally and physically abused them and the pain and hurt that caused. Ali talked about how easily grief can turn into anger and then a person becomes “a ticking time bomb.”

Ali asked the group why people choose to hang onto anger and not forgive.

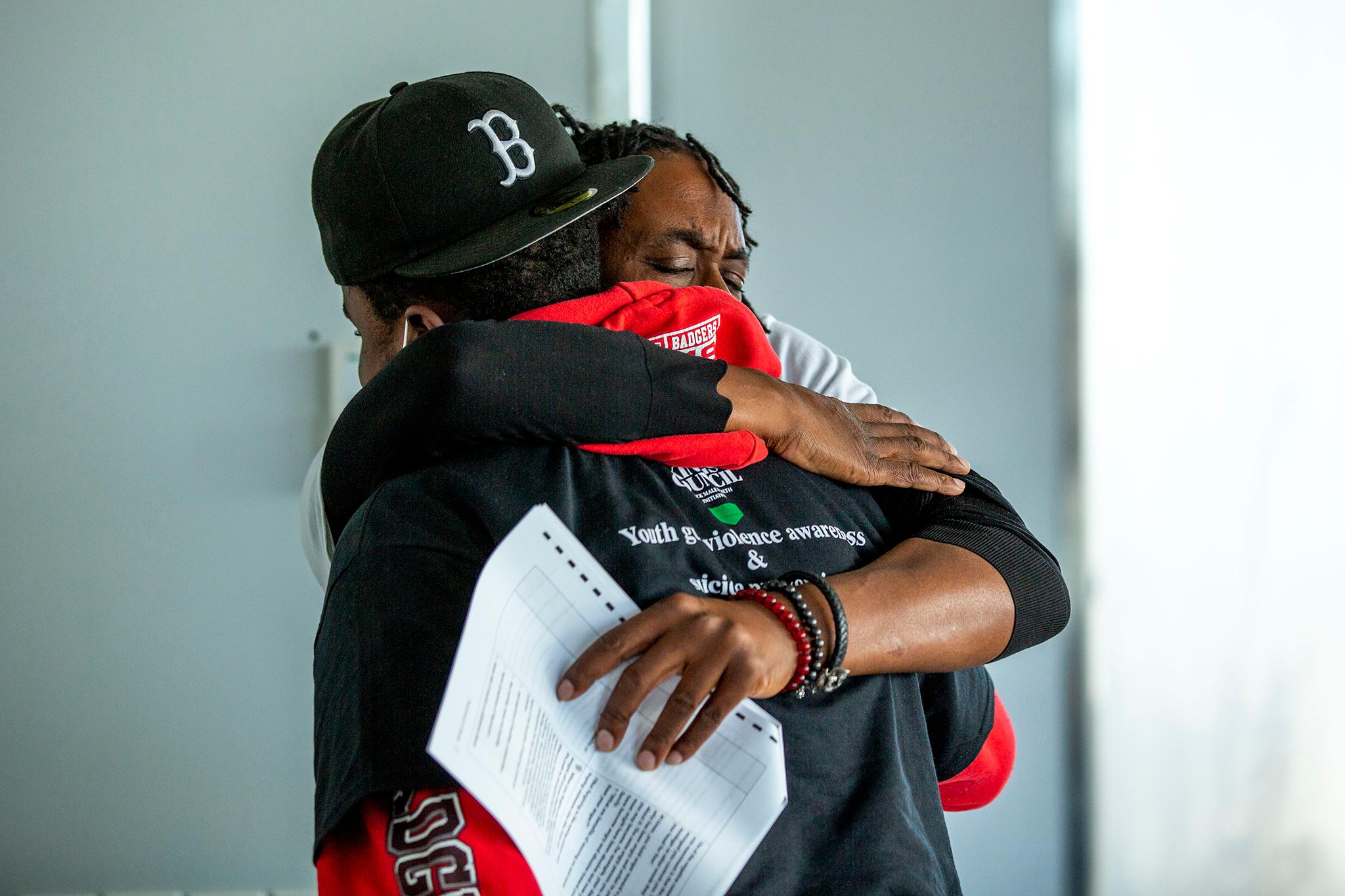

“(I’m) still grieving,” said one teen. Ali walked over to the boy and gave him a bear hug.

The consequences of holding onto anger and resentment can be devastating, Ali said.

“The person who has wronged you controls you,” he said. “They rent space in your head for free! You become that angry person, that abusive person. Not forgiving is like eating poison and hoping someone else dies,” Ali said.

Breakout sessions dig into stressors

Youth attended several breakout sessions like how to build self-esteem, triggers, stressors and early warning signs, building a wellness toolbox — things youth can do physically, mentally, personally, spiritually, emotionally and professionally — to feel better, and having a post-crisis action plan.

Some teens talked about the stress of “code-switching,” having to talk and act different ways in different environments, and being judged in public for how they look.

“And I think that's stressful because it just puts a lot of pressure on you to say the right things and do the right things, in certain times,” said Brandis Cunningham, 14.

Parents, school, tests, and other kids are stressors, the youth said.

“There are actions that can prevent these emotions from overwhelming you,” facilitator Ellis Hudson told a group of boys. The teens created action plans for when stress overwhelms them such as taking a warm shower, listening to music, meditating or walking away.

In another group, facilitators encouraged the boys to contemplate how they express love for themselves.

“I’m still living,” said one boy.

The group discussed ways they will care for themselves mentally, physically and spiritually.

“It’s easier to build a strong child than to repair a broken man,” Elijah Renee, one of the day’s facilitators tells a group of boys.

Changing negative thoughts

Renee, 28, knows that from experience, after being raised by “gang members, pimps and murderers.” He said the more he educated himself and learned, the more he was able to discern right from wrong. He said he sees youth today plagued by the same things that plagued his generation — constant imagery in music and videos that glorifies violence and demeans women.

The group talked about how to change negative thoughts into positive ones by being disciplined and accountable. Renee suggests they label the negative thought and insert it with a positive one.

One boy who said, “I’m never doing anything right” suggests that it could be “I’m doing all the things.”

Renee told the group that they are at a crossroads.

“Now is the time we take back the mind,” Renee said. “Guard your heart, guard your mind, feed it with positivity, feed it with love.”

In another session, a group of boys is asked to name their most important needs and desires and whether their current life fulfills those.

One boy said he doesn’t feel successful at anything and a third said he wants peace in his life but, “I’m not feeling that right now.”

Alex Carter, 17, relies on sports like football, his friends and girlfriend, and when he’s “going through something,” God is a source of strength. Although Carter has excellent family support, a roof over his head, a meal every night and plays lots of sports, he attended Saturday’s session to keep learning.

He’s noticed since the pandemic, more kids at school seem antisocial, more aggressive or don’t want to talk, and Carter is bothered by that.

“(Sometimes) they just ignore me or they just don't know how to use their words, you know, they'd rather text or call me or something, than talk to me in person, you know? And I feel like you learn more and you learn better when you're face to face with somebody.”

The sessions reinforced in him the things he needs to do to uplift himself, like walking in nature.

“In my opinion, that makes you happy, when you put your feet in the grass, it makes you feel good. It makes you feel healthy, makes you feel like you're one with earth.”

Opening up and being real

But regardless of where the young people are on their journeys, they took the first step by showing up to Saturday’s meeting. They walked away armed with lists of things they like to do to feel better and who they can turn to for support.

Near the end of the day, the 14-year-old who got caught with a knife at school was asked what it feels like to see other Black men who open up and be real with him. He answered immediately.

“It feels good. Nowadays, you can't do that. I mean, I can't, I still can't do it. I'm basically telling you the basics. I can go deeper, but this is the basics. So, it feels good to have other people talk to you.”