More than 10,000 Coloradans have died from COVID-19, and Nate McWilliams was almost one of them. The Denver resident went into the hospital in June and didn’t leave until December, and spent three months on a machine that kept him alive. Now, McWilliams is home.

“The fact that he is here, I mean, it's a miracle,” said his wife, Brenda Bailey. “I don't wish this upon anybody.”

It’s Bailey who can tell most of the story of her husband’s illness; he remembers virtually nothing of the months he spent at Swedish Medical Center at death’s door.

“I didn't even know I was in the hospital,” said McWilliams. “It was so bad.”

When he regained consciousness in October, the hospital staff asked him what month it was. “He said June,” recalled Bailey.

McWilliams caught COVID in June. He drove himself to the hospital, spent the night and was released the next day.

But it soon became clear to Bailey that something wasn’t right. Her husband wasn’t coughing, but he was lethargic and having trouble putting together a sentence.

“I said, ‘we've got to go back to the hospital,’” said Bailey. When McWilliams resisted, Bailey said she told him, “you're not gonna lay here on my couch and die.”

It was the beginning of a precipitous decline. The day after he was readmitted to Swedish Medical Center, he was moved to the ICU. Days later, he was intubated. Then Bailey, who wasn’t allowed to be with her husband due to COVID restrictions, got a phone call.

At 7:30 one morning, Bailey got a phone call from a cardiac surgeon. The doctor said that McWilliams needed to be put on an ECMO machine in order to survive.

ECMO, short for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, circulates a patient’s blood outside of the body, which allows the heart and lungs to rest and recover. However, using the machine is considered a last-ditch effort. On average, COVID patients who need the ECMO stay on it for 14 days, with a survival rate of less than 50 percent.

McWilliams stayed on the ECMO for three months.

When Bailey was finally allowed in her husband’s room in July, she sobbed. From then on, she went to the hospital every day. McWilliams says he “kind of felt her” around, and Bailey believes he knew she was there.

“Every time I’d try and leave, his heart rate would go crazy or his blood pressure would go whack,” she said. “And he knew I wasn't leaving until he settled back down. So he always got an extra hour or so out of me.”

There were many times Bailey thought her husband would die. But her determination kept her going, and the medical staff at Swedish supported her. “They were basically my rock when I needed to vent because no one else understood what I was going through,” she said.

Finally, McWilliams started to improve.

He was taken off the ECMO in October and moved to inpatient rehabilitation in November, where he began physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy. After months incapacited by the effects of COVID, he had to rebuild strength just to walk.

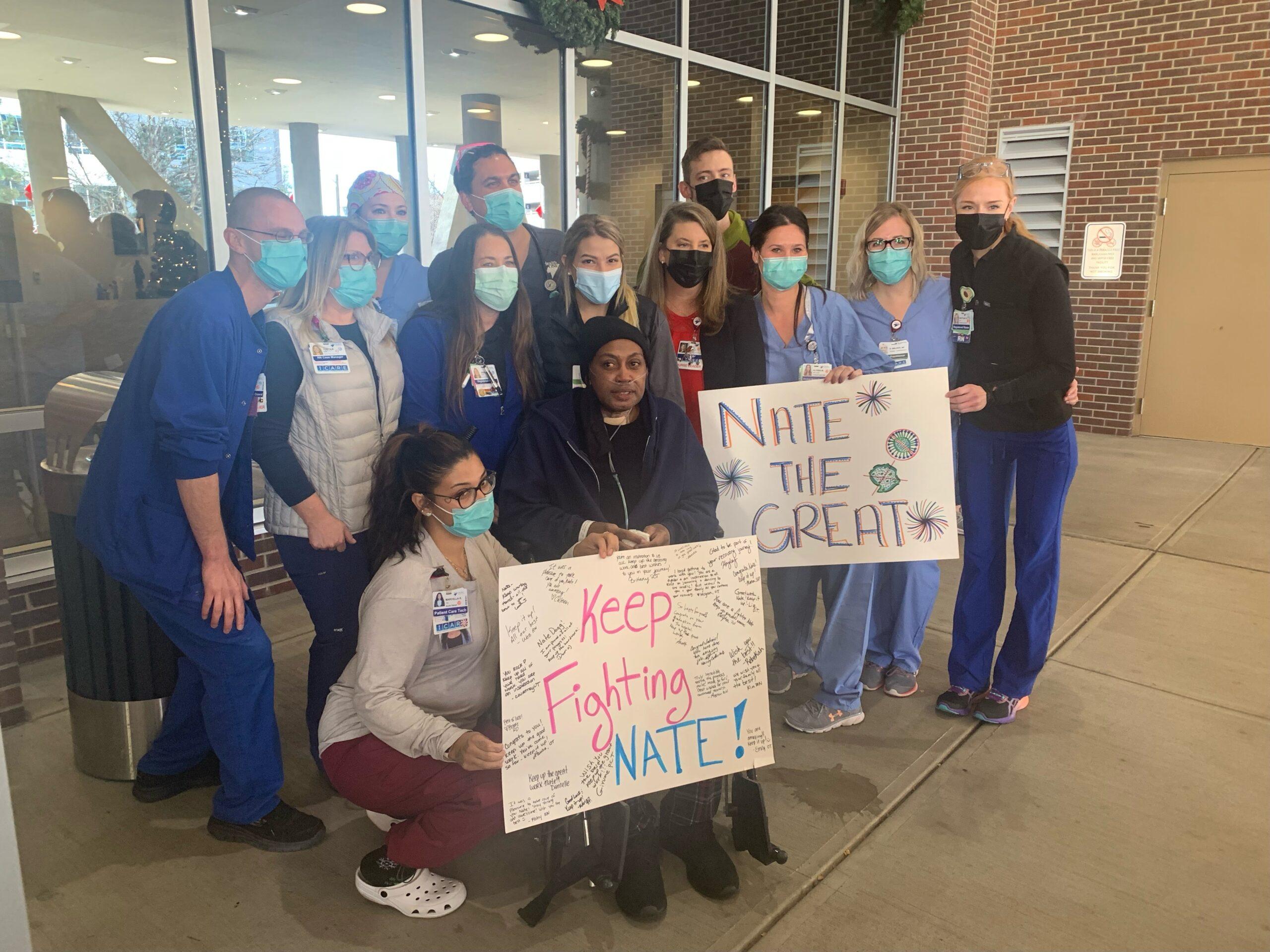

After 158 days in the hospital, he finally went home on Dec. 2, and the staff at Swedish threw a send-off parade.

At home, he still needs supplemental oxygen and is working on rehab therapies.

McWilliams and Bailey were unvaccinated. Bailey says it wasn’t due to any opposition to the vaccine, they just hadn’t found the time. They have since been vaccinated and strongly advocate for others to do the same.

“You don't want to get this. This is serious,” said Bailey. “Not everybody gets as sick as Nate, but you don't want to take that chance.”

Related stories

- ‘This isn’t just a number to me’: UCHealth chaplain reflects on the loss of more than 10,000 lives to COVID-19

- Interview: Gov. Polis leaves mask mandates to local officials, says the state shouldn’t ‘tell people what to wear’

- Colorado patients and providers alike are frustrated, angry and worried as COVID cases pack hospitals across the state

- Last year, Coloradans turned out in record numbers to get their flu shot. This year, not so much

- Omicron in Boulder wastewater indicates community spread of newest COVID variant