A few years back, Colorado State University held a holiday spectacular concert.

And it was spectacular, complete with Santa Claus, a full audience and a packed stage, with an orchestra and choir, and hundreds of people all in close proximity.

Fast forward to March 2020, when COVID-19 derailed concerts, and everything else.

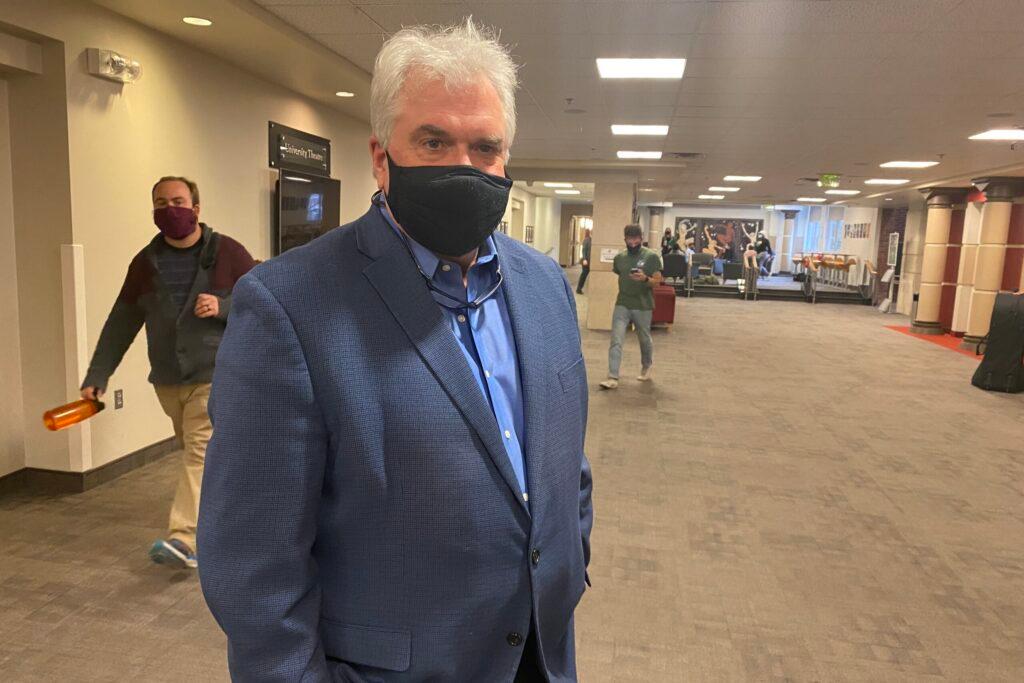

“It deeply affected the performing arts because there was already evidence that the virus was airborne,” said Dan Goble, Director of CSU's School of Music, Theatre and Dance.

Early in the pandemic dozens of members of a church choir rehearsing in Skagit County, Washington caught the virus. Sixty-one people, including one symptomatic member, attended the two and half hour practice. That led to 32 confirmed and 20 probable cases; three were hospitalized and two died. Goble says that rattled the music world.

“Very concerned,” he said. “Not only myself, not only my colleagues here at CSU, but the chat rooms around the country lit up, not just of performing arts at colleges and universities. This is performing arts nationwide.”

Studying aerosols helps us understand how coronavirus spreads.

To figure out how to respond, Goble teamed up with a professor from another part of the university: John Volckens, a mechanical engineer. He studies aerosols, a crucial path of coronavirus transmission.

“Most of the particles we exhale out of our bodies don't disappear, right?” Volckens said. “They stay in the air and they can stay in the air for minutes to hours, depending on the ventilation system.”

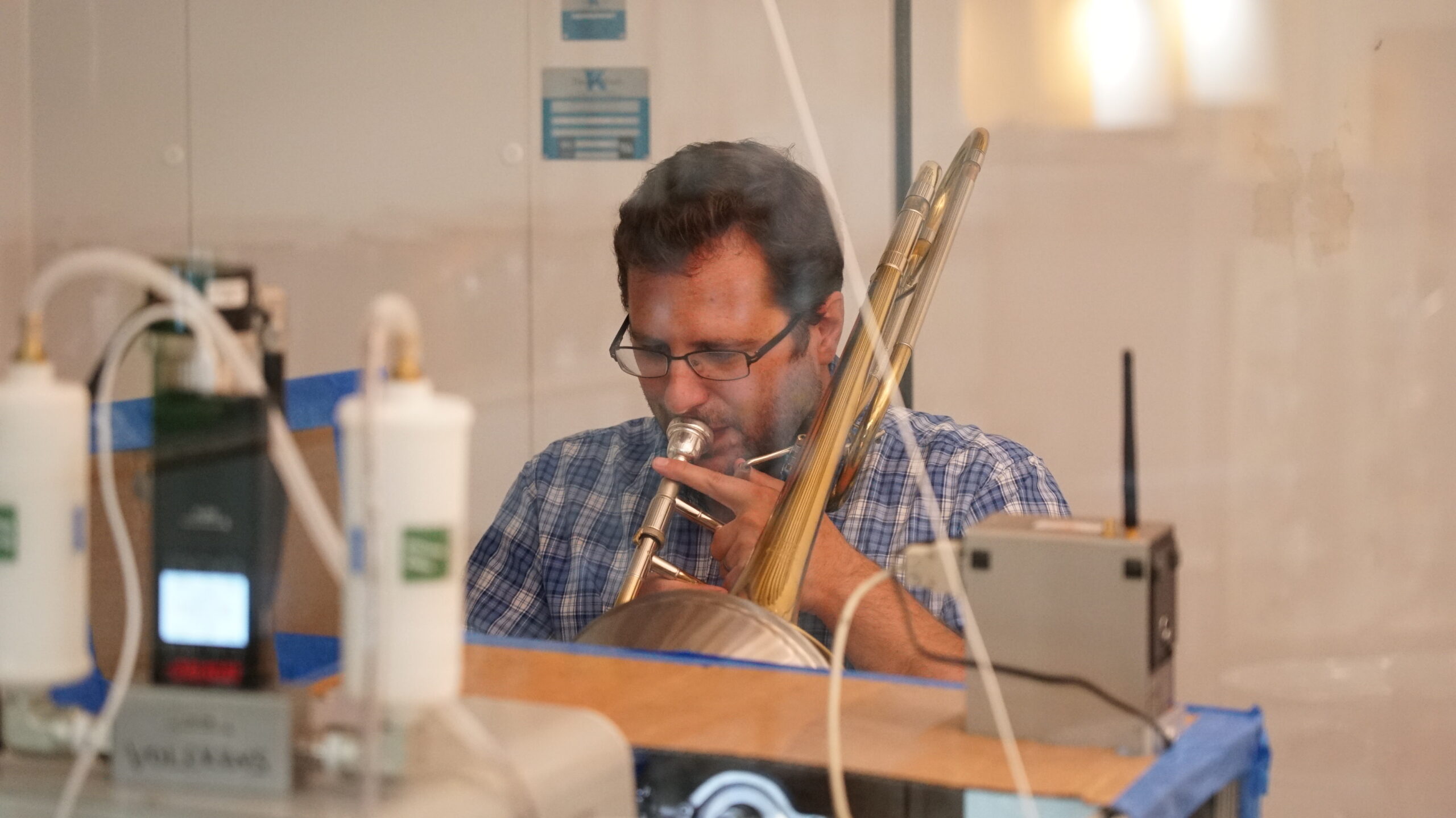

Volckens said there are a lot of questions about how particles spread. But he has the gear to learn more, including a clean room that looks like an aluminum refrigerator with a big sturdy door. Inside is an optical particle counter, which uses a powerful laser.

“Those instruments can count and size hundreds to thousands of particles per minute,” he said.

Volckens and Goble enlisted dozens of musicians to measure emissions. Fourth-year bio-medical engineering student Amy Keisling played her saxophone. When she told friends about the research they were fascinated.

“They were just like, ‘Oh, I didn't realize that that was something that instruments could do, or even something that people could do is spread these aerosols.’”

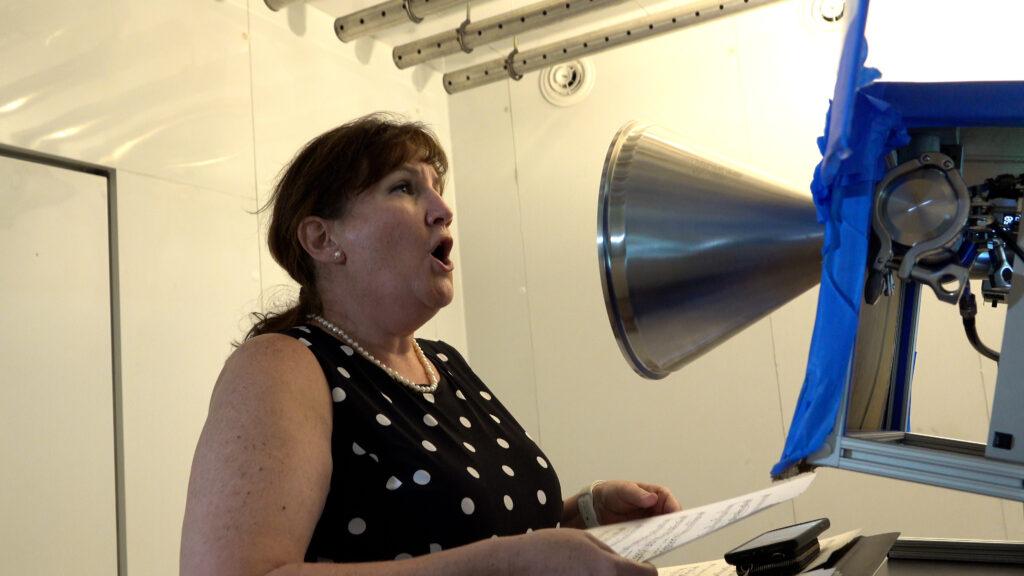

They also measured aerosols from singers, even one from the New York Metropolitan Opera. They’d compare that with the singing of “Happy Birthday” and compare that with ordinary talking. Volckens said they discovered “that when you sing, you emit more particles than when you talk and when you sing or talk louder, you especially emit more particles.”

The study found singing produced 77 percent more aerosols than talking; adults produced 62 percent more aerosols than minors; and men produced 34 percent more aerosols than women.

That data is so interesting, late-night hosts caught wind of it and they had a field day.

“The virus is also more likely to be transmitted by loud talkers, but that singing is worse than talking. Finally, scientific proof that office karaoke night is killing you,” The Late Show’s Stephen Colbert cracked, as his studio audience laughed.

“The jokes were actually pretty funny,” Volckens said, while calling it, “bittersweet for a scientist like me to see my work in the mainstream media, but tweaked a little bit and extrapolated.”

The research did not show that singers, adults and men can spread COVID-19 more, just aerosol particles, but he says that is a reasonable assumption. Still, he says the public health implications are clear.

“A crowded library is probably not as high a risk for a super spreading event as a crowded bar with loud music in the background where everyone's shouting at each other,” he said.

Think of aerosol emissions spreading in a room like cigarette smoke.

Another Colorado aerosol researcher, CU’s Jose-Luis Jimenez, agreed. And he said with the super-transmissible omicron variant here, including in several Colorado locations like Denver, “I'm personally very worried about omicron, as are many scientists because it has spread extremely quickly.”

He said to think of aerosol emissions like the way cigarette smoke can hover and build up. That’s why you should be very careful indoors, “keep groups small, wear masks at all times, except when you are eating, and work on ventilation.”

And that sums up what CSU’s music department did.

"Having the information allowed us to create what we call layered risk mitigation protocols,” said Goble.

The department did hold in-person concerts this fall, pre-omicron. But new rules included extra time between classes for performance rooms to air out and restrictions on occupancy sizes for venues. That's on top of a campus vaccination requirement, with more than 90 percent of students now vaccinated, and a mask requirement, including for singers.

“It was really nice to be able to perform for an audience,” Keisling said. “When we were rehearsing, we would only rehearse for about 45 minutes and then take a 15-minute air exchange break.”

One professor even measured air exchange rates in rehearsal rooms to “make sure that it was safe for us to come back and play.”

The team’s first peer-reviewed paper was published last month in Environmental Science and Technology Letters via open access.

That paper includes results just from the study’s singing and talking experiments; results from instrument playing have not yet been officially released.

But Volckens said those findings are enlightening too.

“Brass instruments tend to emit a lot more particles than woodwinds, which is actually not a terrible finding because brass instruments, most of the brass, you can put a bell cover on,” Volckens said. “So you can knock down the particle concentrations. It's almost like putting a mask on your body.”