At the Ascension Catholic Parish in Denver’s Montbello neighborhood, on a recent Sunday morning, a church band played. Hundreds of people packed the pews. In the front of the room there was a large gold cross, a painting of the Virgin Mary and a bouquet of white flowers.

Every single person was wearing a mask, as a woman with long dark hair stepped up to the pulpit. “Buenos días, mi nombre es Julissa Soto,” she said.

Soto was not there to talk religion or read scripture. She was here to speak about health, specifically COVID-19 immunization. She gave a simple, roughly four-minute message: COVID-19 vaccines are safe, effective, available and can keep you and your family safe and healthy.

In the church parking lot, a state vaccination bus was parked. Volunteers were preparing to give doses as Soto, an independent health equity consultant who works with the state, looked on.

Nearly two years into the pandemic, the new omicron variant is spreading at lightning speed. And whether it’s a product of misinformation, hesitancy, lack of access, or even fear, the number of Latinos in Colorado who are vaccinated lags far behind the share of the white population that is immunized. That could mean trouble both for these residents and for Colorado’s already stressed health care system. But Soto is doing something about those numbers.

“I'm on a mission of getting my community vaccinated and I will not stop until I get the last Latino vaccinated,” Soto said.

By one measure, about 40 percent of Colorado Hispanics five and older have gotten a vaccine dose. That’s 34 percent lower than white Coloradans, according to a recent report from the health research group KFF.

The KFF analysis found Colorado’s vaccination gap between white and Hispanic populations is the second largest in the U.S. and bigger than other western states like New Mexico (-19), Utah (-10), Arizona (-18) and California (-12).

(Note: the government and therefore many research groups use the term Hispanic rather than Latino or Latinx.)

Accounting for unknowns

According to a state analysis, the true number of Hispanic vaccinations is probably better than that, likely closer to 50 percent, but the numbers are skewed because a lot of people, about 10 percent of all Coloradans given one dose, decline to provide that information.

“It poses a challenge as we're trying to make sure that we're equitable across the state and covering every community that we can,” said Will Zigler, the COVID-19 data director with the state health department.

If you look at the state’s COVID-19 vaccine data dashboard, Hispanics make up 20 percent of the state’s population, but just 11 percent of Coloradans who’ve gotten one dose; the figure for those with an additional dose is lower, just 8 percent of all residents who have gotten an added shot.

Officials with the state health department said they realized the nearly 10 percent classified as “unknown” was a problem. So they dove into the data and talked to modelers with the CU School of Public Health. They analyzed U.S. Census data, comparing census tracts of vaccine recipients with known racial and ethnic breakdowns for specific neighborhoods. Based on that, using a geography-based strategy and probability-based surname analysis (called the Bayesian Improved Surname and Geocoding methodology), they could figure out nine out 10 of the shots classified as unknown.

“It really ends up being very precise,” Zigler said.

The state now calculates Hispanics make up about 30 percent of the unknown.

Based on that analysis, the overall percentage of Hispanics with one dose is actually nearly 50 percent, rather than 40 percent, said Zigler.

From the community, in the community

But no one disputes that the Latino population lags behind other groups.

Part of Soto’s strategy is giving shots to Latinos (her preferred term) when it works best. “Most of us organize clinics 8 to 12, Monday to Friday, 9 to 2 p.m. That's a no-no,” she said. “Most immigrants work two, three jobs.”

Soto said her own story connects with this hard-working community.

“I came here 22 years ago, undocumented, uneducated. I crossed the border in the trunk of a car. So I understand the needs of this community,” Soto said. “Now I'm a U.S. citizen. I'm highly educated. I speak two languages.”

That comes in handy because she had lots of questions that Sunday.

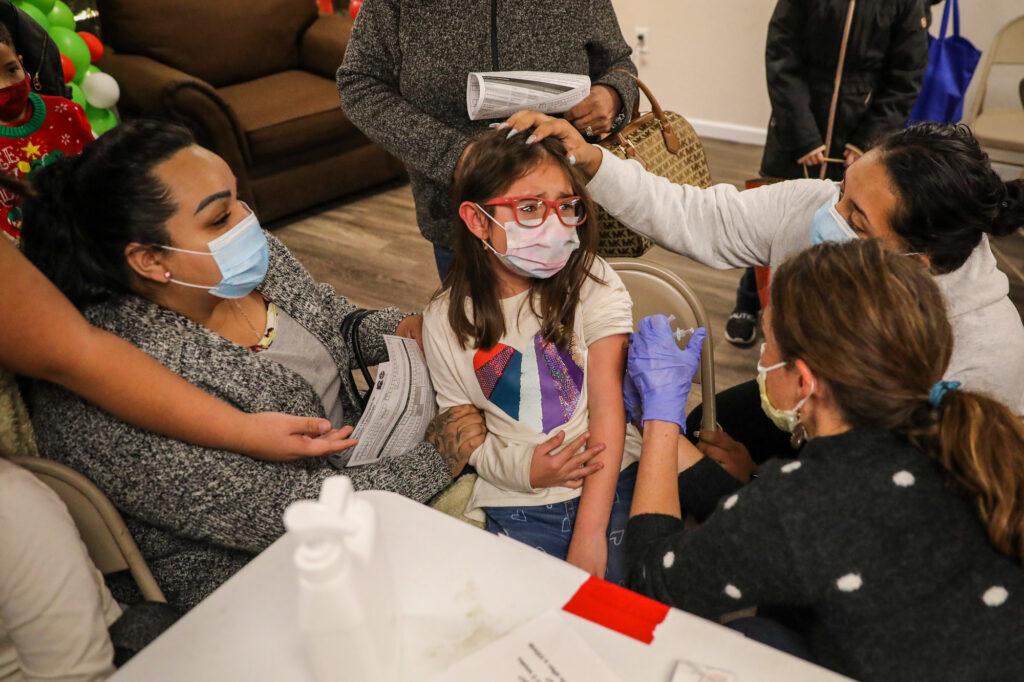

Outside the church, near a table where volunteers were giving vaccine doses, Soto patiently talked to person after person, mostly in Spanish. One woman wanted to know more about boosters. “So she's asking for the booster. She’s saying, ‘Is it true?’ She was asking me, ‘Is it true there is a third vaccine?’” Soto explained.

Soto said her vaccine knowledge is trusted because she’s from the community, and is constantly out in the community, addressing many fears.

“One of the biggest fears is that the government planned this to see who's documented or undocumented. So they can find out who will be kicked out of the country,” she said. “I say no!”

It’s no coincidence this vaccine clinic is happening here. The Catholic Church is an essential community institution. Father Adrian Hernandez, wearing purple garments and a black mask, said the parish is happy Soto is raising awareness.

“It's a beautiful blessing for us,” he said. “I don't know why it's been quite difficult to give the vaccination just going on around the Hispanic community. There is a lot of misinformation out there.”

Hernandez said the parish wants to give this vulnerable population good information so they can choose for themselves.

“So the Catholic Church actually says that either receiving or not receiving the vaccines is not a sin. What could be a sin, could be a sin, is not to receive the proper information,” he said.

For Hernandez, the issue is personal. “Last year around November, I got COVID and it was no fun at all.” He was hospitalized. “It was for four days,” Hernandez said. “Sadly COVID got me before I got my vaccination.”

Many others here have their own COVID-19 experiences, like 33-year-old Maria Chavez. She said she’d heard stories “that it was bad for you and you were going to turn into zombies and all that.”

She and her relatives hesitated to get vaccinated at first. “We didn't even believe in COVID-19 to make it clear. We didn't believe it until it happened in our family,” Chavez said.

When the big COVID-19 wave hit a year ago her dad, Jose, a father of four, got sick. He worked for a landscaping company and was unvaccinated at a time when vaccines were not yet available. And he was careful and always wore a mask.

Still, he got a positive test. But Chavez said he couldn’t get into a hospital.

“No, they didn't have space for him. They were full,” Chavez said. “So they had to wait until someone passed away in order for him to get in.”

Chavez says her father died at home Jan. 9. He was 57.

“That's when you believe in COVID-19,” she said.

After that, Maria Chavez said, her entire family got vaccinated. And she started volunteering, sharing her time and her story at community clinics like the one at this church, where a long line for the vaccine snakes around the outside of the building.

One man here is Rene Brizuela. He works for a cement contractor. He came for a booster and is on board with the pro-vaccine message Soto delivered to the congregation. “That's helped me. Yeah. A lot. Because, some people, from us, we need that information,” Brizuela said. “Sometimes we don't have enough information, you know? So now we know.”

Nolvia Maldonado rolled up her sleeve for her first shot. She’d heard some unsettling things before, she said.

“She's saying ‘When people get vaccinated, you will die right away,’” said Soto, translating.

But a talk from the parish priest persuaded Maldonado. Again, Soto translated. “And the priest was saying that ‘We don't need to be afraid. We need to get vaccinated.’ That this is OK.”

Tara Trujillo, deputy executive director of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, credits community partners, like Soto, with using their contacts and neighborhood roots to reach out “and in places where you could just see people walking across the street, come into the community center to get their vaccine and to get their Walmart gift card,” one of the state-provided incentives.

Not so much hesitance as a lack of access

Some leaders reject the idea that this community hesitates to get vaccinated.

“We're not hesitant. We are not hesitant,” said Nita Gonzales, a regional outreach and engagement coordinator with the state health department. “We have to battle the fact that we don't have what normally other folks have: a health home. We don't have a primary care doctor. We oftentimes don't have insurance.”

Absent those things, she said, many don’t have a convenient, reliable place to take care of routine health needs. “We don’t have that,” Gonzales said. “So we came up against that.”

One community health center, Tepeyac Community Health Center in north Denver, started a more direct route to get the word out: a campaign to go door to door in the Globeville-Elyria-Swansea neighborhood.

“It's been a great opportunity to just connect with people,” and bring them more information about the value of vaccines, said Jim Garcia, the clinic’s CEO. Many folks they talk to have already gotten shots; close to a thousand people who hadn’t yet were directed to a vaccine site.

“We’ve seen from our perspective, from a neighborhood perspective, that we are seeing that level of receptivity, I think, from individuals that are open to getting vaccinated,” he said.

He said he’s not hearing much political opposition in the neighborhood to getting vaccinated, unlike other parts of the state and country. But a handful of residents were adamant about not getting a vaccine shot.

“Within the Spanish-speaking community, I think that the level of misinformation is just as prevalent, if not more so,” than elsewhere, Garcia said. “There's still a lot of work that needs to be done in terms of correcting the information.”

Other community leaders, like Dr. Lily Cervantes, say overcoming misinformation is hard.

“I spoke to a new mom who said she didn't have the time to leave her apartment to get the vaccine and had no one available to help her care for her newborn,” said Cervantes, an associate professor in the department of medicine, at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

The woman worried that her newborn could be infected with COVID if she left her home with her baby to get vaccinated, said Cervantes, a member of the Colorado Vaccine Equity Taskforce. On top of all of this, she said, the mother is undocumented and worried that if her friend was right about the COVID-19 vaccine (that it was created by the government to deport or eliminate them) then she would be separated from her baby.

One can imagine the obstacles and challenges faced by this community if they place themselves in the shoes of a primarily Spanish-speaking Latino or Latina who is an essential worker, supporting a family of four, Cervantes said. They are balancing competing social challenges that are priorities, like putting food on the table, childcare, and working, and have no safeguards.

“For this community, family comes first and self-care comes second and if there are concerns, such as religious, side-effects, or simply due to competing social challenges, they may not get the vaccine,” said Cervantes, who recently wrote about the importance of investing in social services to attain equitable vaccine distribution, in JAMA Network Open .

'We’re coming to them'

A recent study, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, underscores the importance of community engagement, trust building and proactive communication as key to getting more people vaccinated. That is exactly what Soto is doing. She constantly distributes texts and flyers for events at late night concerts, community centers, holiday parties with toys and food, and churches.

An ambitious, multi-faceted approach, with support from community leaders is critical, she said.

“It's the priest, the leaders of our church, leaders like myself, and a place, where it's their neighborhood,” said Soto. “We're coming to them. So they don't have to drive. They don't have to spend money on gas.”

Soto continued. “How is that equity when we have to drive all the way to downtown? Some of us don't even have a driver license. We don't speak English. Where’s the language justice? Is that equity for you? So you tell me.”

The pandemic has hit her community hard, Soto said, and that likely won’t change until more members get vaccinated. That, she said, will take a concerted, long-term push.

“We are about equity and this is what equity looks like.”

Soto is now looking to redouble her efforts. She worries about the super-transmissible omicron variant, with hundreds of thousands of Spanish-speaking Coloradans still not vaccinated with a first dose, let alone a booster.