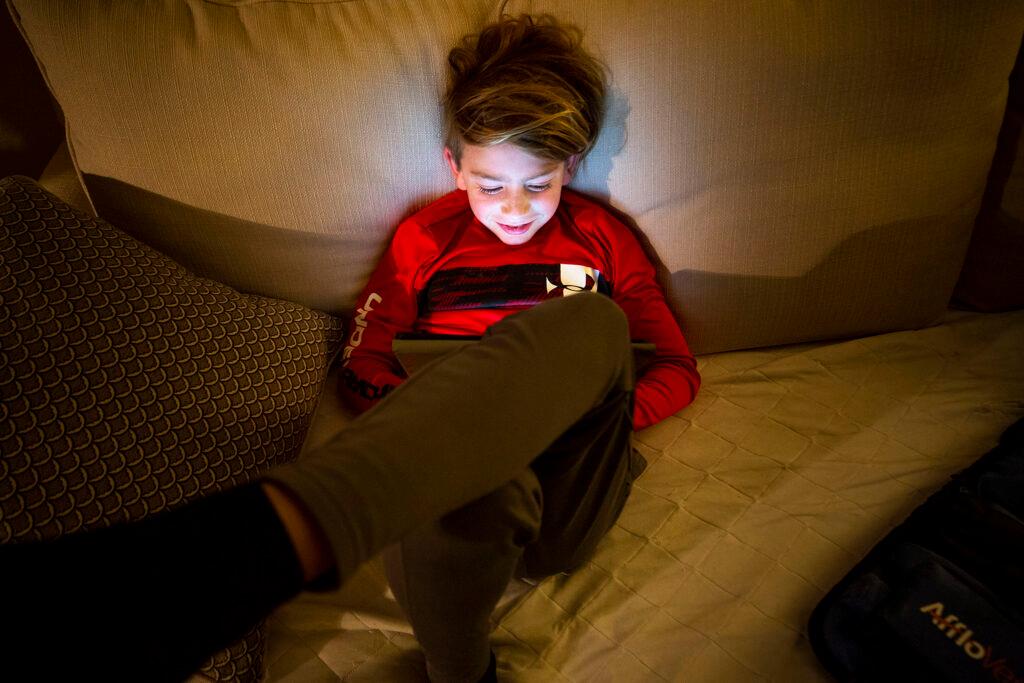

Nine-year-old Jackson Gould is a gymnast, a swimmer, he even does stand-up comedy.

He loves his school in Highlands Ranch.

“I really really like school and learning, mainly the social aspect of it.”

But his mom, Kate Gould, was reluctant to send him back after the winter break because omicron was surging. And masks are not required in Douglas County — Colorado’s third-largest school district. The school board struck the mandate down in early December.

Jackson has cystic fibrosis — thick, sticky mucus builds up and blocks the airways and the ducts in his lungs.

The absence of a mask mandate and confusion over how to handle the highly contagious omicron surges is leaving a lot of parents like Gould with more questions than answers — and more fear about whether to send their children to school. Scant information about how many kids in classrooms have been infected by COVID-19 and not enough staff to track whether infected students are following district protocols has left some parents, particularly those with at-risk children, choosing to keep their children home.

“I feel the way many parents feel now and that is horrified that we have been put into a position where it feels like you have to make a choice between your child’s safety and their education,” Gould said.

Over the winter break, Jackson’s parents asked the school if his classmates could wear masks when they returned from the holiday break. Gould said the district refused twice at first. But it finally relented after a follow-up letter from Jackson’s pulmonologist. Some parents in Jackson’s classroom, upset that their children had to wear masks, threatened to sue.

“It’s shocking,” she said. “It really speaks to how we have lost our moral compass as a society in so many ways.”

Against her “mom gut” Kate Gould sent her son to school. Three days later, Jackson tested positive for COVID-19.

That set off seven days of fever and an underlying pneumonia, she said. He’s also on a powerful antibiotic that keeps bacteria that is colonizing in his lungs from doing permanent damage. He has hours of treatments to clear his airways.

Gould spent the week checking Jackson’s oxygen saturation rates, doing at-home pulmonary function tests, and checking in with the on-call pulmonologist. She moved him into her room, sleeping next to him with a KN95 mask on.

“It’s terrifying,” she said.

The pandemic has brought high emotions and lots of turbulence in Douglas County.

Throughout the pandemic, some county residents have pushed back against masking mandates and other CDC health protocols. In September, the county split from the Tri-County Health Department after 55 years, objecting to health mandates. It formed its own health department. Its first public health order declared that students and staff at the 64,000 student school district didn’t have to wear masks.

In October, the district, along with several parents of children with disabilities, sued the health department in federal court. A judge ruled the mask opt-out violated the Americans With Disabilities Act and masks were reinstated. But the issue didn’t end there.

All last year, families packed school board meetings to protest mask-wearing. They said masks restricted their children’s freedom and hampered social interactions with peers and teachers. Come election time, those families helped install a new school board majority. One of the board majority’s first moves was to drop the mask mandate.

The district directed parents of children with medical conditions to ask their individual principals for accommodations in order to meet federal law. The district said at a January work session two district classrooms are requiring universal masking.

The classroom of Jen Alexander’s daughter wasn’t one of them. So, the 9-year-old missed the first three weeks of school this semester.

It was hard to miss school. Alexander’s daughter loves the singing, dancing, music, art, and tumbling at the Parker Performing Arts School. Her daughter has epilepsy, ADHD, a language disorder and a heart condition. When she gets sick, she’s more likely to have seizures. All that can mean a more serious case of COVID-19.

Despite a letter from her daughter’s pediatric neurologist, it took more than a month for the school to grant accommodations this week.

“This school is where she’s meant to be and she has a right to be there, and she has a right to be there in person, Alexander said.”

Alexander was excited but also terrified to send her daughter with epilepsy back to school this week. She likened it “to sending her to the Hunger Games arena. It's like, may the odds be forever in your favor. And, hopefully, this isn't the day that I send you to school to possibly end up in the hospital or the ICU, or even worse.”

Last week, Alexander filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights.

“It's impacting a lot of people and it's being shoved under the rug. All I'm trying to do is to give a voice to my child, to fight for her rights. And quite honestly to fight for the rights of these other kids as well, because somebody has to fight for them. They need a voice,” she said.

Kelly Mayr pulled several of her children out of school last week. Her daughter in high school has significant disabilities and when Mayr dropped her off at school, she saw very few masks.

She said many of the education assistants who help with children with disabilities are getting sick.

“These are scary times. It is very surreal around where I live in Douglas County. It just seems like people are pretending that there is no pandemic and life is just going on, which is terrifying and frustrating at the same time.”

How many kids are getting infected with the omicron variant?

Douglas County School District Superintendent Corey Wise said despite the elimination of mandatory masking, the district’s COVID-19 infection rates are similar to other districts so far.

“We're doing well. It's not great. It's not perfect. We could be better … we're maintaining, we're sustaining and learning is happening,” he said at a recent board work session.

But many parents suspect the infection rates are much higher than what’s reported on district COVID-19 trackers because many families aren’t reporting cases. An open records request shows student attendance in the district, though rising now, was about 88 percent on Jan. 14. It’s typically around 93 percent.

“Prepare for the worst and hope for the best,” wrote one high school administrator to his staff at the beginning of the semester.

Omicron brought the worst and was met with what parents say is a very confusing protocol.

Parents are confused about when to send their children to school if they’ve been exposed to COVID

Students who test positive for COVID do have to isolate for five days. Last week the district stopped sending exposure notifications to other parents, who were receiving dozens a week. The district said parents found them confusing and they were often sent well after the exposure because COVID-19 testing lags.

“Telling you that you’re exposed is like telling you that you woke up this morning,” said board president Mike Peterson in a January work meeting. “Assume your child has been exposed, whether that is in the school, whether that is shopping, whether that is in a playgroup, whatever, just assume all being exposed to some form of omicron on a daily basis for the next few weeks.”

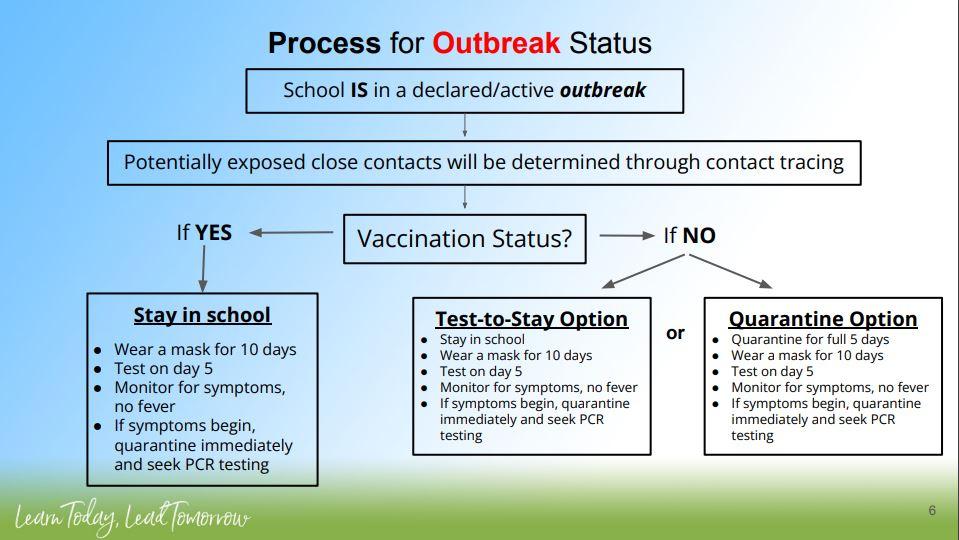

In situations where there is an outbreak — five COVID-19 cases connected to one person – the district changed its policy about notifying the whole school. Instead, it will only notify close contacts of the positive case. It’s so confusing, the district has a flow chart to help parents.

School board member Elizabeth Hansen questioned what she said is a complex system that has different options depending on whether a student is vaccinated or unvaccinated.

“Our staff are at the edge of what they can maintain,” she said. “That’s an extra burden that we're putting on our staff and we don't have the data to actually follow the process that's in place. It's just fluff. It's giving our community a false sense of a mitigation structure that’s actually not in place in terms of monitoring the data when it comes to who's wearing masks, who's not wearing masks, should they be wearing masks? Were they exposed? Who's been vaccinated? Who hasn't been vaccinated?”

Hansen said it’s difficult to ensure safety when so much is reliant on whether parents are following the protocol.

“I think the message our community has heard is parent choice, parent choice, parent choice, parent choice,” she said.

Members of the board’s majority disagreed. Board president Peterson said along with parent choice, they’ve tried to emphasize individual responsibility. “But we also have strong recommendations – if you believe you are sick, certainly we're recommending you to stay home.”

Superintendent Wise acknowledged the district can’t track everything, that there is a bit of an honor system.

But some parents believe the system is denying them choice — a safe and healthy choice.

“The refrains of 'parent choice' are also frustrating because I do not have the choice to send my child to school where CDC recommendations for masking are being followed, and I don't have the choice to do the online version of school because it's full,” said Leigh Picchetti, mother of a fifth-grader and seventh-grader.

Charmaine Quinn agrees. She has an unvaccinated 2-year-old at home and when omicron hit, she didn’t want her older child bringing home COVID-19. Quinn is also the sole caregiver for her grandmother.

“Masking, it gives everybody a choice. If you’re expecting me to send my daughter to school in a situation I clearly think is dangerous, the only thing I would ask is that there are masks on all of the faces, because it gives me the choice,” she said.

Teachers will provide homework packets for children at home sick with COVID-19, but district policy doesn’t allow that for keeping a child home whose parents don’t feel safe. Quinn’s 9-year-old daughter has dyslexia and needs the specialized support she was getting in school.

“I am already seeing her beginning to struggle all over again.”

Parents are also confused about whether absences will be excused if their child is at home not sick. Some say they’ve been told they’re not. The district says that’s being handled on a case-by-case basis between parents and principals.

Nine-year-old Jackson Gould puts on his vest to clear his lungs of mucus.

For all of his 9 years, his mom Kate Gould said they’ve tried to keep him as healthy as possible so he could have as normal a childhood as possible.

That’s meant an hour or more of airway clearance treatments a day. On a recent night, the family’s Pichon dog, Preston, jumps up on the couch to be next to Jackson, wearing a thick blue, electric vest that vibrates his chest, which vibrates his lungs, which loosens the mucus in his lungs. He’s taking 35 pills a day.

“Walking that rope between wanting to wrap him in bubble wrap and wanting him to have a completely normal life,” Gould said. “It's devastating as a parent, it's devastating to my son who doesn't understand why his school doesn't want to protect his health. He's just this amazing kid. And he takes it all in stride and he works hard to stay healthy. And the school system, the place that I send him to every day, believing that he will be protected there and cared for, they've taken that away from us.”

But Jackson is an upbeat kid who tries to take things in stride. He’s someone who sharpens his stand-up skills in his downtime — “It’s just a regular pandemic, am I right?” — does gymnastics, plays piano and, tonight, starts planning his diorama for a school project on the Mexican American war.

Gould has set up a GoFundMe campaign to hire a special education attorney to fight for an injunction to bring back universal masking.

In her quest to raise funds for a legal fight, she’s buoyed by a recent Pennsylvania court ruling that ordered a Pittsburgh area school to keep its mask mandate to protect medically fragile students. And Colorado’s own court ruling last year to restore masks.

Long term, however, as is the case with several other families contacted by CPR, the Gould family is looking to move out of the county for the next school year. Some didn't want to be named in this story, fearing retribution.

“I’ve gotten enough threats from other parents that we don’t feel safe,” Gould said.