Brad Wham was surrounded by flames as he evacuated his Louisville home during the Marshall fire on Dec. 30. The next day, he hopped on his bike and rode through the wreckage left by the fire, which spared his house but destroyed others hundreds of yards away.

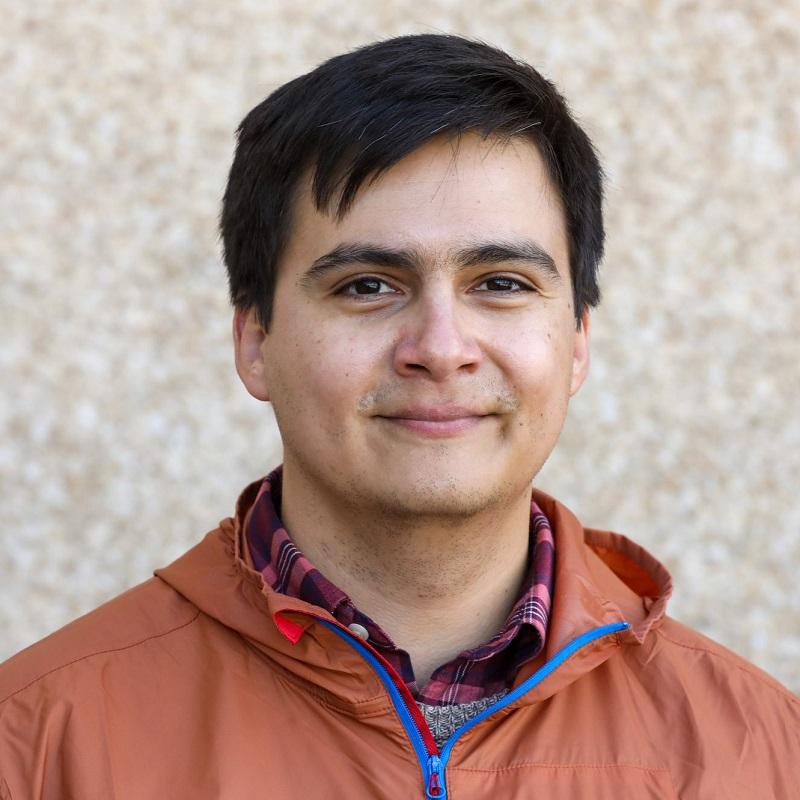

That bike ride began the structural engineer’s study of the most destructive wildfire in Colorado’s recorded history. Wham, an assistant research professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, has since been joined by researchers from across the country to gather information about the fire that will be used by academics and local governments preparing to rebuild.

Wham and his colleagues were among the first researchers on the ground in the area burned by the Marshall fire. His team, which includes university students, has focused on collecting data and images to create detailed maps of the fire scar.

“There is a huge area that burned here — some 6,000 acres — and to gather the level of detail in this entire area takes many weeks,” Wham said last week from the burn scar in unincorporated Boulder County. “So we’re honing in on some of the areas that we think are most important, where there’s most to learn from immediately.”

The Marshall fire spread rapidly through grassy open areas baked by drought and unseasonably warm temperatures, conditions scientists say are more likely due to climate change. The grass fire quickly became a suburban inferno, capturing the attention of Boulder’s own renowned scientific community and researchers around the world, who are proposing studies on everything from the economic impact of the fire to how many pets were lost or killed during the evacuation. The researchers can be well-intentioned but disruptive; in a virtual meeting earlier in January, one state emergency official said residents have asked that they stop showing up at their homes.

Wham and his research partner Erica Fischer, an assistant professor at Oregon State University, are trying to gather data in a respectful way that ultimately benefits the communities affected by the fire. They coordinated with other groups looking for similar data, including Purdue University and Geotechnical Extreme Events Reconnaissance, a volunteer organization sponsored by the National Science Foundation.

“Every disaster — aside from the devastation that it causes — is an opportunity for learning,” said GEER co-chair Shideh Dashti. “It’s like a giant laboratory that, before the data is erased, we want to learn from so that we can prevent the damage next time.”

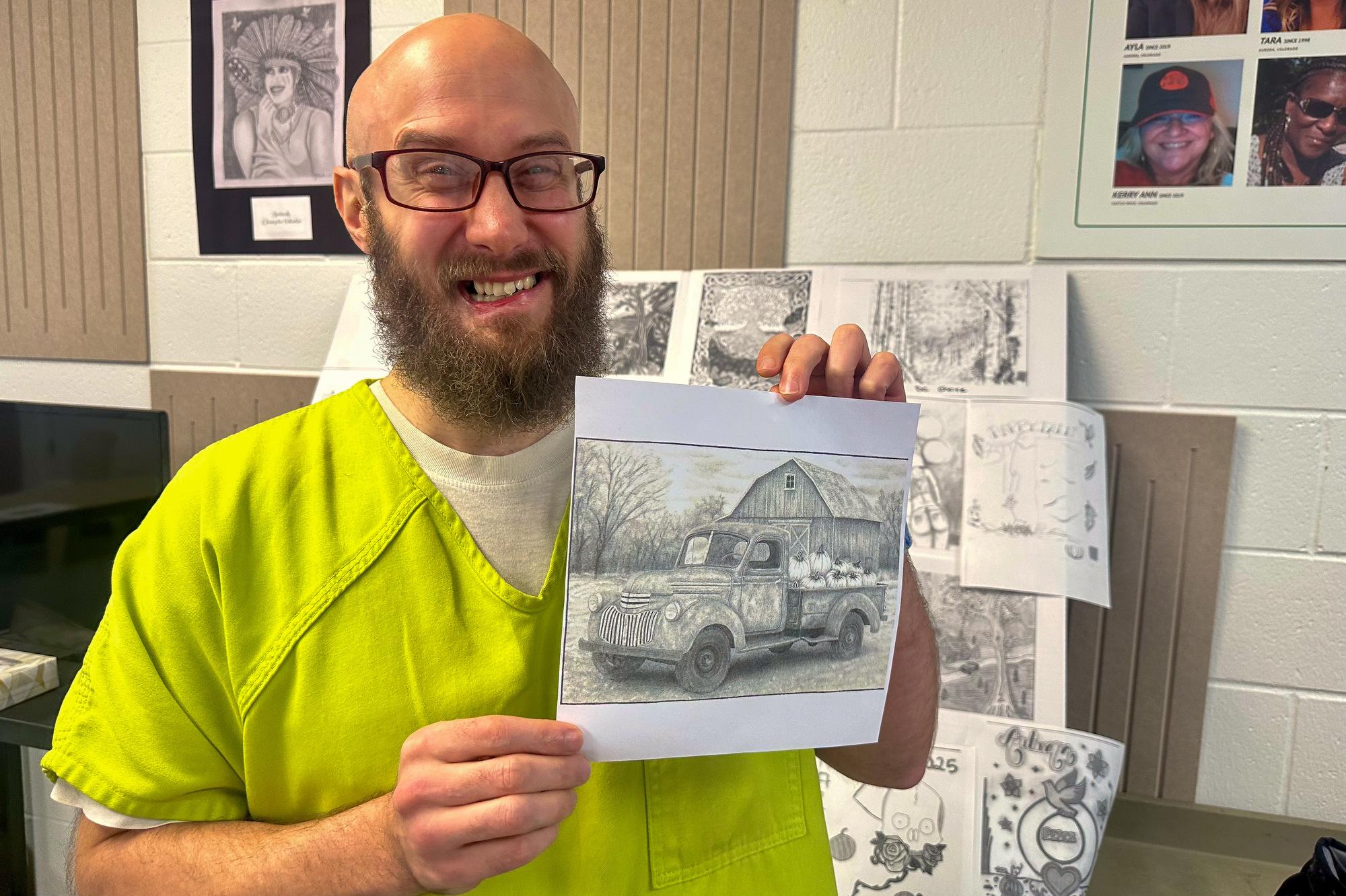

The research team has taken aerial images of different sections of Louisville and Superior that burned in the fire. On Friday, the team flew a drone with four rotors above a cul-de-sac on the northeast section of the burn scar.

Fischer, who also studied the 2018 Camp fire in California that killed more than 80 people, said communities burned in the Marshall Fire were unprepared for the spread of wildfire. She hopes the images and data captured by the drone are used to learn why some homes avoided the fire while others nearby burned. She said governments could also use the data across the West to improve building codes and mitigation efforts.

“This isn’t an incredibly rural community. This isn’t a 200-person town. This isn’t a community that’s struggling to provide basic resources to their residents,” Fischer said. “When you take away that lens, what you’re able to look at is how they’re going to recover … when you have people who can recover.”

The GEER team is expected to have an initial report from the drone flights within a month, Wham said. Fischer and Wham are also studying whether the fire degraded the local water distribution system and potentially contaminated its water supply.