Rising crime | The politics | What the data says

New statewide data on Colorado’s crime rates puts hard numbers to what many in law enforcement have been saying for the past 14 months: Crime in almost all categories started going up before the pandemic and continues to rapidly rise.

Violent crime, which counts homicides, aggravated assaults, sex assaults and robberies, is up 17 percent between 2019 and 2021. Murder is up 47 percent in those two years.

Property crime is up 20 percent and auto theft is up 86 percent between 2019 and 2021, according to the Colorado Bureau of Investigation.

A one-year analysis done by the FBI between 2019-2020 found Colorado had the fourth-highest increase in all crimes in the country — just below Pennsylvania, South Dakota and Utah.

More statistics, according to a Colorado Bureau of Investigation comparison between the years 2019 and 2021 include:

- Juvenile aggravated assault with a firearm is up from 29 percent of all aggravated assaults in 2016 to 44 percent of all aggravated assaults in 2021.

- Burglary rates fell between 2016 and 2019 but climbed back up in 2020 and have flattened since.

- Identity theft rates have more than doubled from 121 crimes per 100,000 people in 2019 to 396 crimes per 100,000 people.

Searching for an explanation

Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen, who has been making presentations all over the metro area about the state’s crime rates and solutions he hopes are tackled at the state legislature, said he thinks there are multiple “layers” of problems happening at the same time.

“Colorado, historically, has been a remarkably safe state, well below the national averages … we can’t say that anymore,” Pazen said. “I study this crime data on a daily basis and we have significant challenges. Until we come together and are even willing to admit we have a problem, I’m not sure how we’ll be able to get this fixed.”

Pazen doesn’t believe the current spike in crime has anything to do with the pandemic.

“Please tell me how a virus makes people commit more crimes, makes people steal more cars, increases the number of shootings we have?” he said. “The state of Colorado has emerged from many of the mandates earlier than other states, yet the last four months have been remarkably high for homicides.”

Pazen thinks lawmakers and other state leaders need to evaluate laws passed in recent years — policies that lessened penalties for certain crimes like auto theft and drug possession — to see whether they contributed to a more dangerous Colorado than in years past.

One anomaly in the numbers

Over the past two years, prosecutors across the state say they have tried to hold as many people accountable as possible for that 17 percent increase in violent crime.

And yet, the total number of district court criminal filings was down last year.

That’s because district attorneys aren’t tackling as many drug cases.

State prosecutors filed about 7,500 fewer drug charges in 2021 compared to the previous year. In fact, there were 51,378 felonies filed in 2020 and 43,834 felonies filed in 2021, according to the Colorado Judicial Branch.

A 2019 possession law that reduced penalties for carrying up to 4 grams of almost all drugs to a misdemeanor, which means the cases are instead sent to county courts for prosecution.

Indeed, county court drug charges climbed in a single year from 4,150 filings to 7,270, according to the state judicial branch.

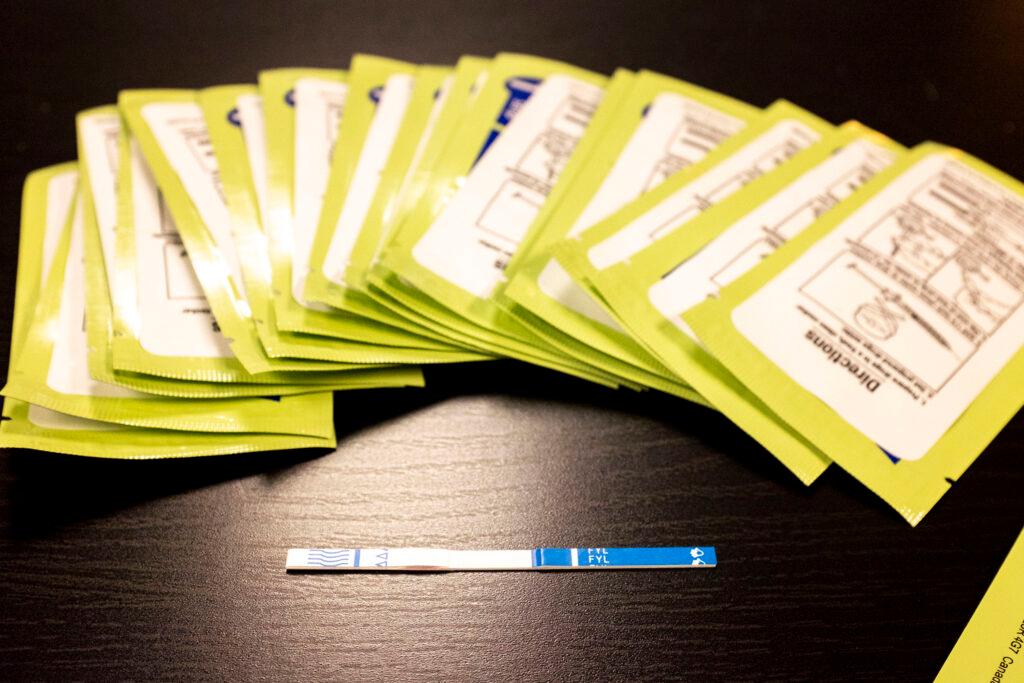

This comes at a time when fentanyl and methamphetamine seizures went up by four-fold in a single year by the Colorado State Patrol and fentanyl overdose deaths went up more in Colorado than any other state in the country — except Alaska — between 2015 and 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

“There’s nothing compassionate about leaving a heroin user or a fentanyl user or a meth user on the street or arresting them and turning them back out,” said Tom Raynes, head of the Colorado District Attorney’s Council. “You’re just enabling the addiction and that doesn’t help anybody.”

Christie Donner disagrees.

She is the head of the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition and has worked on reducing mass incarceration in Colorado for decades.

Donner worries the current debate about how to tackle the increase in overdose deaths will mean an overcorrection in strengthening drug laws that will disproportionately hurt poor people and men of color. She compared it to the crackdown 30 years ago during the crack epidemic.

“It’s always challenging when you have these kind of knee-jerk reactions to things. It can take 20 years to unravel the harm that’s been done,” Donner said. “It’s like, ‘been there, done that.’ I need to get a perm because we’re back in the 1980s. And I laugh, but it’s not funny because this will have substantial impacts on people’s lives.”

The fentanyl problem

Lawmakers are amid a closed-door debate about what to do about fentanyl — considerations include repealing the misdemeanor law from 2019 and strengthening penalties for dealers.

Already, state and federal prosecutors are working in this space — both have increased the number of murder charges against distributors.

Just last week, the Colorado U.S. Attorney’s office announced a 175-month sentence for a 45-year-old Fort Collins man who distributed fentanyl that resulted in death.

“The one thing we can deal with on our side of the equation is the supply piece,” said Cole Finegan, Colorado’s U.S. Attorney.

James Karbach at the state public defender’s office said he feels a regression back to policies 20 to 30 years ago that didn’t reduce drug overdose deaths or make communities safer.

He noted a number of criminal justice reform measures passed in recent years — including pre-trial reform rights and lessening penalties for certain non-violent crimes — helped his clients by making the justice system more fair for economically underprivileged people.

“It’s politically expedient to claim it’s criminal justice reform,” Karbach said. “But we also know that Colorado has some of the lowest funding for mental health treatment in the nation and so some of these gaps can contribute to things like substance abuse and problems in the community.”

Karbach believes pandemic behavior fallout had deep effects on everything from an increase in homelessness to unemployment, kids being out of school and untreated mental illness.

All, he said, contributes to a higher crime rate.

“Attributing what caused the rise in crime when the economy was struggling and the pandemic was raging … it’s multi-faceted,” he said. “It’s a complex problem with complex causes and solutions.”