It’s a Wednesday and Dr. Shen Nagel, a pediatrician, is at work.

“How’s he doing?” he asks with a bright smile, as he leans in to talk to a mom at Nagel’s clinic in Wheat Ridge, Pediatrics West.

“Good. He's a really happy baby,” says Lea Green as she cradles 4-month-old Knox. He’s here for a check up. “I mean, he sleeps really good.”

Green said her family did catch COVID-19, twice, but she’s hoping the virus is winding down.

“We're fine,” she said, “otherwise just glad to rarely wear masks anymore.”

Like all Colorado medical facilities, this one pediatric clinic weathered hit after hit from the pandemic: battling the virus, economic troubles, staffing shortages. The troubles and the innovation at the clinic have been repeated at health facilities across the nation as the pandemic wears on, and perhaps they’ve helped prepare them for future surges that may come.

For Nagel, enduring the last two years may have made his practice stronger.

“While a lot of people are feeling sort of frayed, we probably are, as a staff here and providers here, a bit more resilient,” he said.

But it meant changes, which are apparent as Nagel tours his clinic, including a cut-out, where families could take a picture to capture a pure pandemic moment.

“On the back wall is a photo op we made for patients getting their COVID vaccines,” he said.

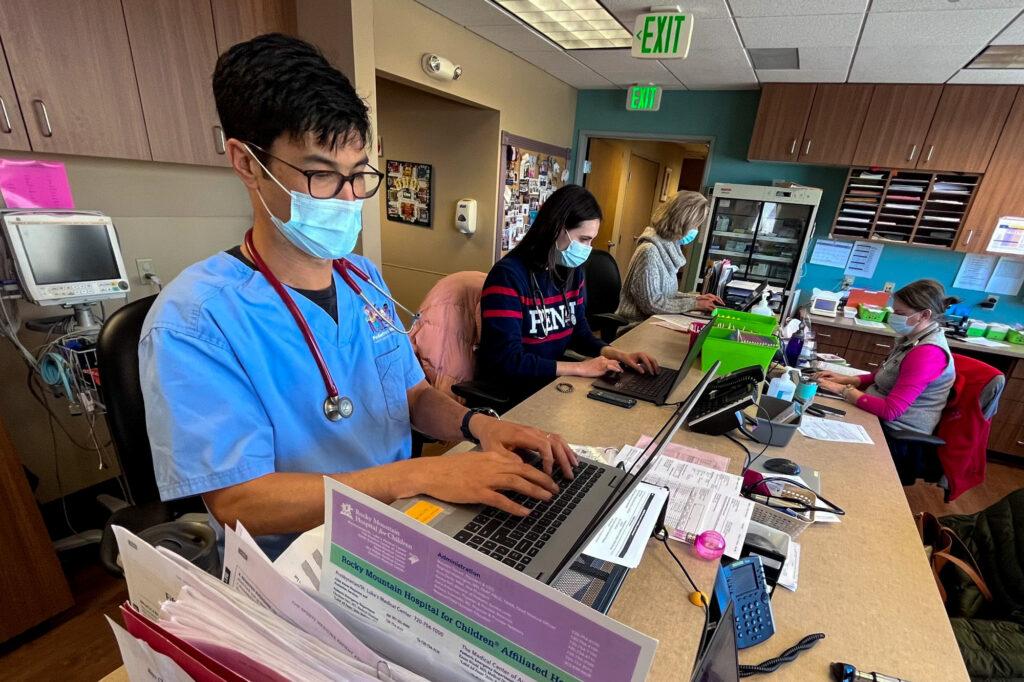

The practice serves 12,500 people, so things get busy.

With a highly contagious disease running around, they aimed to limit groups of sick people congregating by de-densifying our waiting room, Nagel said.

Sick patients and families are to wait, distanced, in the hall and call the front desk. Clinical supervisor Christy Parker showed one way the clinic manages the flow of sick patients, through a waitlist and queue management app called Waitwhile.

“They just get a direct text message that will tell them the instructions,” said Parker. “And then when we're ready for them, they will get another text message telling them to come up stairs.”

“It is definitely a new pandemic thing for us,” she said.

Parker said that’s just one example of the clinic innovating, out of necessity. “It has been crazy. It's been a whirlwind of chaos,” she said.

The chaos started in spring of 2020. And it wasn’t just a health crisis. With a stay-at-home order and social distancing, families avoided primary care clinics.

Revenue dropped off a cliff, Nagel said. “That was a lot of sleepless nights,” he said..”

One in five people in Colorado skipped some type of care in 2021 due to cost — deciding not to see a primary care doctor or specialist or leaving a prescription unfilled, according to the Colorado Health Access Survey. That report is produced annually by the Colorado Health Institute.

The survey found the impacts of COVID-19 went beyond infection: Many reported having reduced hours or income (29 percent or 1.3 million people); struggling to pay for basic necessities (17 percent or 738,000 people); struggling to pay rent or a mortgage (17 percent or 723,000 people); or losing a job (17 percent or 510,000 people).

Nagel said the clinic did use telemedicine visits early in the pandemic, mirroring trends statewide in the survey. But that tailed off as families became more comfortable with in-person visits and as reimbursements from payers grew less consistent.

“We still do some, primarily for behavioral health follow-ups, but very rarely for sick visits or well checks anymore,” he said.

The clinic employs more than 50 people. When the crisis first hit, Nagel worried about layoffs and pay cuts. Federal relief money helped them avoid the worst, providing $700,000 to the clinic through the Payroll Protection Program. “If we hadn't had that, we would've been in a very different place in terms of probably having to furlough people, lay people off, take pay cuts and things like that,” he said.

As the crisis wore on, there was burnout and turnover: employees making life changes, dealing with day care and retirements.

“We've been for two years, almost in a constant cycle of hiring new people and trying to train them up, so that takes a lot of our staff time, energy and bandwidth,” he said.

Physicians nationwide reported anxiety, burnout, and depression negatively impacted many primary care practices, according to a report in 2021 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Another source of stress: hostility from some families over hot button issues like masks, which are required in the clinic.

“There was a contingent, a small contingent, but nonetheless it was there that was much more confrontational and less appreciative of things. And that really wore down our staff and providers as well,” he said.

In many ways, the practice is a microcosm of what happened all over. But in recent weeks, COVID-19 transmission, cases and hospitalizations in Colorado have all dropped. Nagel says the lull, powered by both vaccination and infection, comes as a relief.

“At least for the next few months we hope there's pretty widespread protection and we might be in a pretty good place,” he said.

In an exam room, Megan Licher, a mother of three, visited the clinic with her youngest, a wide-eyed 5-month-old.

“This is Harrison. He's a bit of a butterball,” she said.

The little guy has tape on his temples, to hold tubes for the oxygen that’s pumping into his nose. He needs it because of a non-COVID, cold-like respiratory virus his brothers brought home.

“For him, it went into his chest and he's been on oxygen for the past three days. It's kinda scary for a mom,” she said. “We got some good news today that he hopefully will be able to come off of it. So that’s good.”

But, just as that’s hopefully resolving, another issue is popping up. Her first-grader, John, goes to a school now easing its health safety rules. Licher has mixed feelings.

“And they just took the masks off and he said, ‘Mom, it feels safe to have it on, can I leave it on?’” she said.

These sorts of questions are the kinds many pediatricians face.

Nagel says young patients are just starting to crawl out from under the cloud of coronavirus. He hopes they’re building skills for coping and resilience “that will serve them well going forward. But I am worried about this COVID generation.”

Last year, Children's Hospital Colorado, declared a "State of Emergency" in youth mental health.

The Colorado Health Access Survey 2021 underscored the same trend. It found adolescents (11 to 18) saw their rate of poor mental health double since 2017, from nearly 9 percent to 18.5 percent in 2021. But more of them spoke about their care with primary care providers or mental health professionals in 2021 (32 percent) than in 2017 (23 percent).

Looking at the pandemic, mom Licher borrowed a phrase from Mr. Rogers, saying it’s good to identify the helpers.

“It's easy to get really sad about what’s happening but you know look at all the people who are helping and standing up to help their neighbors,” she said.

And for Licher, that surely includes her family’s primary care providers.

Correction: A caption in an earlier version of this article misspelled Ty Blach's name.