If anybody could work the system and get access to wildly popular open space this summer, you’d think Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commissioner Taishya Adams would have a good shot.

But there she is, just like everyone else, penciling early March on her planner as the day she can first swing sharp elbows online to get summer group backpacking reservations at Rocky Mountain National Park, not far from her home in Boulder.

“I’ve had it marked in my calendar for six months,” Adams recently told her fellow commissioners. She endorsed a new timed entry proposal for Eldorado Canyon State Park, where overflowing parking lots on weekends back up onto lawns in the little town of Eldorado Springs.

But she added a warning message: Intergenerational families love the big picnic areas at Eldorado and other state parks. They come in more than one car. Managing crowds by managing cars should not shut out diverse uses of state open space.

“I would hate to see that become a barrier,” Adams said.

Everyone agrees Colorado’s open spaces are growing alarmingly crowded on popular days. The numbers are startling.

Visitation at close-in Front Range state parks has doubled or nearly tripled. Sprawling Lake Pueblo had to turn away cars for the first time in 2020, the year it passed 3 million visitors. Jefferson County Open Space does not have gated entry for counting, but believes visitation to its 28 foothills gems passed 7 million last year.

Staunton State Park near Conifer rocketed from 89,000 in 2015 to 277,000 in 2020. Barr Lake in Brighton, a hit with birders and flatland bikers, went from 119,000 in 2015 to 258,000 in 2020, before settling back a bit with indoor pandemic restrictions easing in 2021. Open space officials expect use to keep climbing rapidly, if not quite as steeply as in the first year of the pandemic.

A Center for Western Priorities study of reservable camping spaces at federal and local public lands showed more than 95% of sites were taken at peak periods, with an overall 39% increase in summer camping at public spaces.

And the state parks commission may have just opened the gates on a new flood — the annual Keep Colorado Wild state parks pass will be only $29 in 2023, tacked on to annual car registration with an option to decline it, less than half the current $80 fee for one car.

Open space managers across the West are scrambling to accommodate the growth without provoking a public backlash against new rules. Mandatory shuttles from remote lots, parking fee add-ons, timed entry, seasonal trail closures for wildlife protection, and extra fees for non-residents are all under consideration in every parks-related office.

“You do have to be ready to say OK, first come, first served doesn’t work if you have an entrance line that’s a half mile long every day,” said Aaron Weiss, deputy director of the nonprofit Center for Western Priorities, which advocates for expanded public lands and more parks funding. “We have to find a better solution.”

The answer can’t just be forcing everyone to online reservation systems or discouragingly high fees, Weiss and others say. The fix has to include more open land, they argue, including the Biden administration’s executive order seeking to protect 30% of U.S. land and water by 2030.

“Increased use of state and federal lands is a good thing, and the solution isn’t to curtail access, but rather increase it by conserving more land and removing barriers to entry from those who feel excluded or unable to access the outdoors,” said Jackie Ostfeld, director of Sierra Club’s Outdoors for All campaign.

“The threat of overuse poses in these small spots, and it is a legitimate threat, is miniscule compared to the threat posed by development,” Weiss said.

Anecdotal evidence and polling data show the online ticket jockeying and the turned-away cars, from Pueblo to Roxborough, are altering the way Coloradans use — or try to use — the great outdoors.

About 58% of Coloradans said crowding in the last two to three years has changed where and how they recreate, according to this year’s annual State of the Rockies Project poll of Western states by Colorado College and New Bridge Strategy. The average across all eight Western states polled was 48% changing their time and location of outdoor recreation.

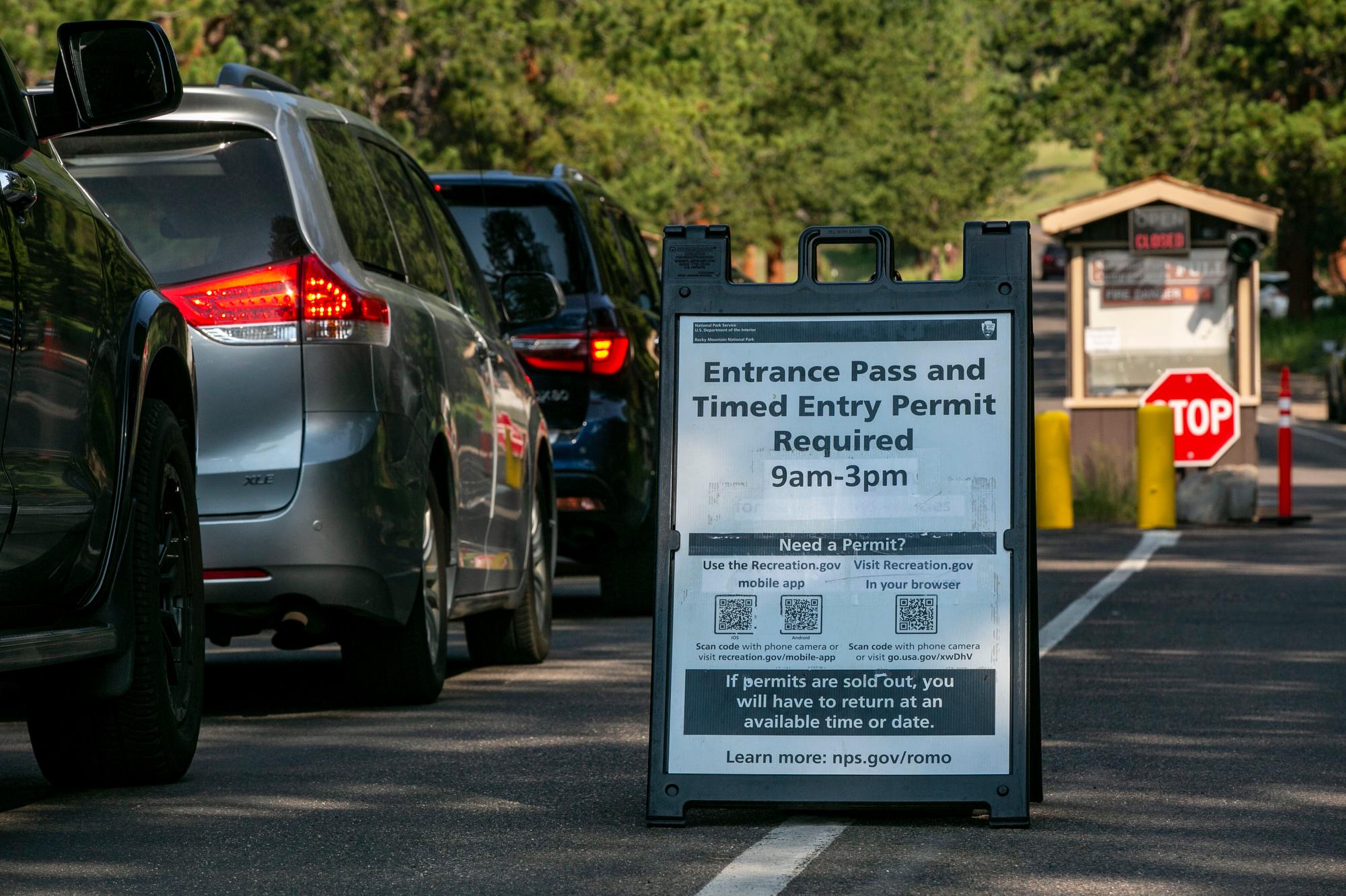

Larimer County hiker Suzy Paquette said she understands the need for control experiments like timed entry, but added that the online regimen started at Rocky Mountain National Park last year did change how she and her husband get outdoors.

Even on weekdays in the summer, the national park passes are “gone like lickety split,” she said. “So that’s one of the problems, you can’t just say ‘Oh, let’s go to the park today.’”

It’s not just the human visitors and residents whose behavior and attitudes are impacted by the outdoors rush, said Dana Bove, a volunteer who helps keep track of eagles and hawks at places like Barr Lake, St. Vrain, Boyd Lake and county parks. He feels he’s lost his own “solace” in the crowded parking lots and packed trails, but worries more about the birds.

“These days, most of my walks on the trails where we live are at dusk or in the evening,” Bove said. He can choose to walk later, but he said, “wildlife is not so fortunate, as they have already moved away or been displaced from the ever increasing human traffic.”

Pueblo is proud that people come from all over to boat on Lake Pueblo, swim at Rock Canyon, or mountain bike on dozens of miles of trails, said Jamie Valdez, who has led mountain bike classes at the state park. Pueblo gets less snow, and the warm winter sunshine attracts recreation from multiple states, he said.

Valdez has his eye now on the city’s Pueblo Mountain Park, with its own hiking trails in the foothills southwest of town sitting as a hidden gem. “It’s a beautiful, beautiful park, and it seems to be almost forgotten,” he said.

The nonprofit Boulder Climbing Community weighed in early on the proposed changes to how Eldorado Canyon is managed, knowing many of its members go dozens of times a year and count on driving, rolling or striding in just a few minutes after class or work.

To their credit, Boulder County and the state have consulted closely with climbers on improving the shuttle to the park and making sure timed car passes aren’t hoarded or sold, said Boulder Climbing Community executive director Kate Beezley. The shuttles have spaces for climbers’ crash pads and other gear.

More controlled-entry rules for open space are inevitable, Beezley said, so parks managers need to make sure they consider all the user groups and keep things fair.

“Who is the primary user group? Who are your frequent flyers? And how can you help them maintain those patterns of their health and well-being?” she said.

Parks managers flinch when they think of the potential overuse coming to stunningly picturesque, newly minted state parks like Sweetwater Lake in Garfield County, and Fishers Peak near Trinidad. Weiss, of the Center for Western Priorities, uses the word “harden” to describe how open space planners must anticipate the places a frenzied public will park, hike, build fires or camp, and create protections for those natural areas.

Marketing experts also must join in to help spread people out by showcasing alternatives to the closest, most Instagrammed locations, experts say.

Otherwise, Weiss said, the great outdoors becomes “this massive Disneyland problem that you end up with at Zion National Park, or at Chautauqua for that matter. There’s a lot to be said for making sure folks are aware, hey, there are equally great if not better experiences, because it’s less crowded.”

Angel’s Landing at Zion is one of Weiss’ favorite spots. But it’s no fun, he said, “If it looks like the line to ‘Pirates of the Caribbean.’”

So what else can be done? Scott Roush, who oversees some of the busiest Colorado state parks close to the Denver metro area, said park users should expect more experiments with timed entry like the one moving forward for Eldorado Canyon this summer.

Highline Lake State Park is a place managers worry about, he said. Parking lots fill fast on weekends at the rare body of water in the high desert near Grand Junction. Without more parking controls, people leave their cars wherever they feel like it, just as at Eldorado Canyon, Roush said.

Jeffco Open Space is adding new parking spaces at Alderfer/Three Sisters Park outside Evergreen, community connections director Matt Robbins said. That may head off “volunteer” parking. Jefferson County also puts stock in educating park users on simple, highly effective tips like staying on the trail even in mud season. Hikers sidestepping mud create “braiding” that turns single track into 4-foot-wide throughways, Robbins said.

Charging for parking or timed ticketing are tougher, Robbins said, because Jeffco does not have controlled entry at its 28 parks in the way national or state parks do. The county did try an experiment last year partnering with Lyft for $2.50 off rides to and from open space parks. It was a bust, Robbins said.

Federal, state and county cooperation is key to pulling off more successful management techniques, said Dan Gibbs, executive director of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources. Gibbs lives in Breckenridge, where one of the busiest 14,000-foot peaks in the state, Quandary, beckons from the south.

County officials worked with the U.S. Forest Service to implement a reservation system for county-owned lots at Quandary’s base, and a shuttle system for remote parking areas.

“In these high-usage areas, I think that’s going to be the future, whether it’s on state lands or federal lands,” Gibbs said.

Roush said some state parks planners are interested in trying technology aids like Lot Spot, a smartphone app that Jeffco uses to provide real time updates on park crowding and can recommend a nearby alternative. State parks are much more spread out, though, than county open space, and alternate choices may not be practical.

The public appears to be adapting to shuttle use as a way to control car overcrowding, and park planners have noticed. Eldorado’s shuttle system will run again in 2022. Shuttles to Rocky Mountain National Park’s Bear Lake are now an essential part of park operations. Buses now operate to control entry to Maroon Bells and Hanging Lake. Expect more.

“Do we have an actual number-of-people problem, or do we have a number-of-cars problem? Because there are different solutions there,” Weiss said. “And shuttles are of course part of that.”

Another part could be other public transportation, added Weiss, who lives in Jefferson County. “Here, there are no RTD routes that get you to open spaces. That’s a problem.”

Open space managers at all levels of government are doing a better job consulting with each other and with private businesses expert in usage information and technology aids, said Tate Watkins, a research fellow at Montana’s free market oriented Property and Environment Research Center.

Reservation systems at Arches and Rocky Mountain national parks are closely watched by state and county parks managers, Watkins said. Technology companies can offer ideas on counting parking space use, “frequent flyer” perks, and integrating real-time crowding information on apps that can spread out park visitors.

Backcountry users of Great Smoky Mountains National Park — which saw 14.1 million visitors in 2021 — initially balked years ago at implementing a $4 reservation fee for remote camping spots, Watkins noted. Now they think it’s a bargain, and are relieved to know there’s a spot open for them at the end of their day.

“There’s just an infinite amount of creativity and opportunity for experiment,” he said.

Open space fans and park managers worry that new layers of control and costs will widen the already large gap between tourists and outdoors enthusiasts with time and income, and those on tight budgets and less access to technology.

Fees are adding up at every level, Eldorado Canyon hiker Jeff Paquette said.

“So now you have the annual pass for your state, the annual pass for your county, and before you know it, it’s going to be for all open space,” he said.

The Sierra Club is among those fighting for more open space and recreation opportunities closer to cities, Ostfeld said. By Sierra Club’s definition of “nearby,” 100 million Americans lack easy access to open space.

“We must be very careful to ensure that the actions of public land managers don’t perpetuate the status quo, with many communities already feeling unwelcome or unsafe in some of our national and more remote parks and public lands,” Ostfeld said.

Being mindful of everyone’s time and resources is key to designing open space access, Weiss said.

“One thing we’ve learned from all of this is that any sort of time system where a clock turns over and everyone is mashing a button to try to get in, that is not fair and equitable,” he said. Some space needs to be reserved for lottery or last-minute access for those whose lives can’t revolve around one reservation window.

Colorado leaders say they are aware of all these pitfalls, and will keep working to avoid them. The new $29 state parks pass linked to motor vehicle registration will bring in money to add new parks, experiment with reservations, expand shuttle systems and more, DNR’s Gibbs said.

He said he still prefers to look at access as a good problem to have.

“In the long run,” Gibbs said, “we want people to get outdoors. I mean, this is Colorado.”