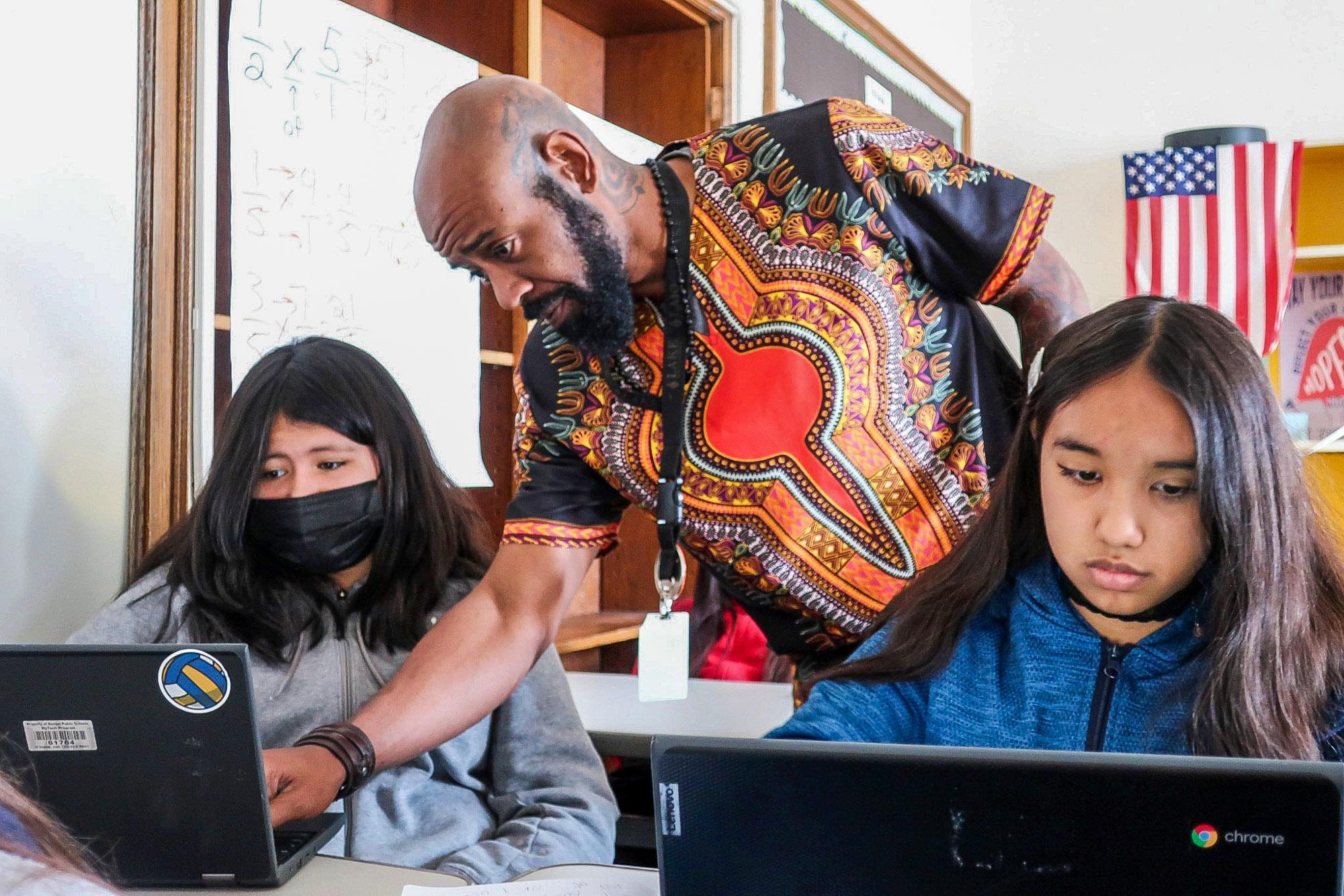

Patrick Jiner moves from student to student in his seventh-grade math class at Lake Middle School as the students roll dice to learn about probability. He’s always on his feet. Jazz plays lightly in the background.

“What is the probability of not rolling a six?” he asks as he leans in to help a student.

Back-to-back classes and lots of assignments to grade and lessons to plan await him. So, before an interview, a reporter asked if he wanted to get a drink of water.

“Oh no, this is teacher life!” he laughed. “We don't go to the bathroom. We don't get drinks. We eat and run. It's just how we roll.”

Jiner may make a joke, but it speaks to the sheer volume of things teachers have on their plates. Half of Denver Public Schools staff surveyed by the district recently felt their workload was unsustainable.

“Every teacher leaves the school with homework to take home, work that they didn’t have enough time to take home during their workday and it does affect your next day job if that work isn’t done,” he said.

Two surveys of Denver teachers found widespread feelings of burnout and distress, and educators on the verge of quitting.

Teachers describe massive workloads, without the time or support to do their jobs: teaching children. They also describe inadequate mental health support for students with challenging behavior. Another theme is an extreme divide between school staff and the district’s central administration.

In the district survey, only a third of staff responded. Usually, two-thirds do. It asked staff how engaged they are — whether they enjoy their work, feel it has a positive impact and feel valued. During the height of the pandemic, engagement was around 75 percent. This spring it had dropped to 57 percent.

Teachers had the lowest satisfaction, at 51 percent of teachers. Principals, school counselors, and psychologists were not far behind at 56 percent. Staff who provide special services like nurses, audiologists and physical therapists were at 60 percent.

Anthony Smith, DPS’ chief of equity and engagement, said the district received more than 3,000 written suggestions on what teachers need to feel valued.

“It goes from more planning time, some teachers said, “I just need not to have to sub anymore. I need mental health supports. I need behavior supports. I need curriculum supports.’ And we're taking that and we're going back and saying, how do we make this doable? How do we help them achieve success for kids? We have to have happy teachers to have successful kids and the district is committed to that.”

He said in conversations with teachers and administrators, they’re struggling to understand whether the lack of engagement stems from the pandemic and the challenges it presents or whether it’s a consistent feeling.

“But I also see a need to feel valued by your district, to want to know that ‘we matter,’ to want to know that our district cares about us, that our schools care about us,” Smith said.

'We struck a nerve,' said Karen Mortimer, chair of a district advisory committee, which also surveyed teachers.

The District Accountability Committee survey distributed the anonymous survey to better understand challenges faced by school-based staff.

The 601 responses were tabulated in December. This survey was conducted at the height of the severe staffing shortage in the fall, which could have been a factor in the overwhelming stress staff were experiencing. Teachers also place a lot of stress on themselves, particularly when students are so far behind academically because of the pandemic.

“We take it personally when our test scores come back, and kids aren't where they need to be. If you're a good teacher, it’s going to affect you,” said Jiner.

But according to the surveys, in general, despite being the people closest to students day in and day out, teachers do not feel district leadership listens to them about what students need.

“This should have been a year for us to work on changing the face of education, instead it is more of the same, with less time and resources to do things,” wrote one DPS teacher in the survey.

Many teachers painted a picture of a district in crisis, with high numbers of teachers overwhelmed and considering leaving at the end of the year.

The atmosphere and work conditions are very dependent on a school’s leadership.

Some school staff said their school leadership is excellent, and their schools are united and collaborating.

“Although mentally, physically, and emotionally exhausted themselves, suffering vicarious trauma, they continue to move forward, taking one step at a time, to support and guide our students and staff daily. They listen to our staff and their needs and do everything that is within their control to help us,” said one DPS teacher in the survey.

Jiner feels at Lake Middle School, teachers and students have buy-in on school decisions and teachers are encouraged to express opinions. He’s been in other schools with toxic environments.

“They're really hard to work with, right? This is one of the most beautiful jobs you can have. You work with young people all day long and to come in and feel that kind of energy amongst the staff, you know it's trickling down to the students,” Jiner said.

Others in the surveys do not feel supported by their school leadership, which is driving many teachers and staff from the profession. “Toxic” was a term frequently used when describing school environments.

The No. 1 thing teachers in the DPS survey want is flexibility and autonomy.

Some teachers say scripted curricula hamstrings their ability to engage students. Preschool teacher Amy DeFusco moved to a school this year that has a more flexible curriculum. But even so, the documentation it requires is hefty.

“I have to take pictures of each student to document, and I have over 20 objectives, and I have 27 students right now. I have to have at least three pictures for every objective for every student,” she said. “And that I'm supposed to just be doing during the day, collecting this documentation, uploading it.”

That is just one task. Other teachers point to myriad requirements on top of teaching, such as the district’s LEAP teacher evaluation system, Capstone projects, SLOs (student learning objectives), READ Act requirements, the Equity Experience (an equity learning module), data meetings, professional development meetings, state department of education reading modules and standardized testing as initiatives and requirements that could use streamlining.

Every year teachers make similar complaints about the bureaucratic requirements but nothing changes, they said.

“Things just keep getting put onto our plate. But nothing ever seems to get taken off of our plate,” DeFusco said.

Excessive workload is the biggest staff concern that they said prevents teachers from having the time to meet academic, mental, social and emotional needs of students.

Math teacher Jiner would like to see more “tangible, financially feasible” solutions to building efficiencies around lesson planning and data inputting.

“To waste time inputting 99 or a hundred standards or scores on a spreadsheet. It literally is a daunting task that I have little patience for,” he said.

The district’s Anthony Smith says DPS is committed to trying to lessen the load.

“What I don't want to do is over respond to the event (the pandemic.) And then the next survey we see is that teachers don't feel like they're getting the feedback they need to get better… So then how do we collaborate with teachers to understand how best to make the workload manageable and still meet the needs of our kids?”

He wants teachers at the table as the district continues building its strategic plan.

Jiner is collaborating with district leaders and board members to bring teacher suggestions into DPS’s plan. He’s hopeful but “to steal a phrase from politics, trust but verify, right?”

The DAC committee also is meeting with the district to strategize on how to address teachers’ concerns. Mortimer would like to see a solid inventory of every single thing on educator’s plates to determine if the district has control over it.

“If they have control over it, can they remove it from the teacher's plates? Can they lessen the burden that is on the teachers because of whatever the district is requiring of them?” Mortimer said.

Secondly, identify who is advocating for changes at the state level to lessen teachers' burden, “so that aspects of their job that are truly honestly just exercises in paperwork, they're not helping the children, how can they be rid of them because teachers cannot survive another year of what they experienced this past year.”

Students' emotional and mental health challenges ramped up this year

Between the burnout, the workload and the stress of the pandemic, teachers also pointed to another major challenge that materialized this year: students who don’t know how to be in school.

“The district's current policies on banning suspension and punitive behavior management practices are inappropriate and are making school an unsafe place for teachers and students,” said a teacher in the DAC survey.

Many teachers reported an escalation of student behaviors, especially among students who never exhibited problems before the pandemic. They said accountability for student behavior is inconsistent across the district and consequences for inappropriate behavior are lacking.

“We have had a student make multiple threats to staff and students, and the student has not had any consequences,” wrote one staff member.

Schools also don’t have enough mental health support or support for students with disabilities, teachers said.

“The whole system was not prepared for the challenges that the kids were going to face being back in person,” said the DAC’s Mortimer.

The district’s Smith said teachers and administrators are trying to discern whether students’ lack of practice at being at school is leading to worse behavior problems and teachers' lack of practice at handling behavior issues is partly what’s made the year so hard.

The district is trying to reduce disproportionately high rates of suspending students of color and can’t “demonize or over criminalize our kids for being kids after they've been cooped up,” Smith said.

He agrees that teachers need the tools to deal with tense situations without ignoring the rest of the class — something teachers hadn’t practiced in more than a year and a half. He said that came through clearly in the surveys.

“Not like, ‘Oh my God, I'm so frustrated, but I need help. I forgot what it's like to deescalate a kid,” Smith said. “And I'm really seeing that they're struggling because they're frustrated because a fourth-grader who was in elementary school is now in seventh-grade and they really haven't had school. So, they're not used to this. And how do I reacclimate to what it means to be a student?’”

While some teachers surveyed complain about a lack of funding — state lawmakers and Colorado voters share the blame for that.

State lawmakers have used a mechanism for more than a decade that has resulted in withholding more than $10 billion from public schools. That’s so they can balance the state budget each year. Colorado voters have also turned down several ballot measures to fund education. Consequently, the state spends $3,000 less per student than the national average. This year the average per-pupil spending was about $$9,015.

That’s led to huge class sizes in many Denver schools, which also takes a toll on teachers.

“If I had all my students today, I would have almost 30 kids in the classroom,” said seventh-grade math teacher Jiner, looking around his classroom. He said other teachers have 35 or 36 students.

“That becomes overwhelming when you're looking at trying to grade 36 papers every day. It's overwhelming for teachers. And it creates a lot of burnout.”

Many teachers say their schools also lack adequate support staff — like classroom aides and other mental health supports. Preschool teacher Amy DeFusco said her school is well-staffed compared to others. She said her teacher friends, particularly those in northeast Denver, are being hit harder by the staffing crisis.

“There are extra needs already in those communities and a community that's already lacking, definitely needs more supports,” she said.

In the meantime — DeFusco sees teachers new and old looking to get out of the profession. For herself?

“I very much love my job. I'm very invested in it. My grandma was a kindergarten teacher. My other grandma was a kitchen manager. So, we've always just had this love for education in my family. I don't see myself going anywhere anytime soon, but I'd like to make it better while I'm here.”

Some of District Accountability Committee’s recommendations for improving teacher and staff engagement include:

- Lighten educator workload (that includes recommendations to let teachers teach, analyze district initiatives that are not critical to student learning or legal requirements, minimize meetings.)

- Addressing staffing crisis (enact district-wide tutoring to support student learning, encourage community volunteerism)

- Focus on mental health and behavioral supports

- Increase staff support to enable effective teaching (adjust curriculum expectations so teachers can engage students, increase access to lesson plans for teachers, focus on getting students to grade level.)

- Adjust school scheduling to carve out more staff time (adjust schedules to allow breaks to recharge and plan b. Consider hybrid schedules or remote days to provide staff planning time, rethink school days to help educators work with students with greatest needs.)

- Respond to reports of unhealthy school environments (Hold school leaders accountable, listen and respond when staff call attention to problems at a particular school, interview teachers and staff without administration present to truly understand challenges.)

- Develop meaningful ways to show staff appreciation (Provide bonuses and increased compensation for staff, especially for substitute teachers and paraprofessionals; encourage communities to resume intentional staff appreciation activities.)

- Advocate for change at the state level a (Support state efforts to pause school accountability systems for 2022 school year. Advocate revision of SB 191, the teacher evaluation bill.)

- Heal the “Central vs. Schools” divide