Director Steven Spielberg’s glittering remake of the musical West Side Story is up for seven Academy Awards Sunday.

It’s not the first iteration of the story to win critical acclaim. A 1957 Broadway version was edged out for the Tony Award for best play. The 1961 film won 10 Oscars. Along with the honors, though, both of those versions were full of racist stereotypes: Song lyrics painted Puerto Rico as a haven of poverty and gun violence. The casts were overwhelmingly white, wearing makeup and chattering in fake accents to portray Puerto Rican characters. The film's lone Puerto Rican, breakout star Rita Moreno, was forced to wear brownface right along with them.

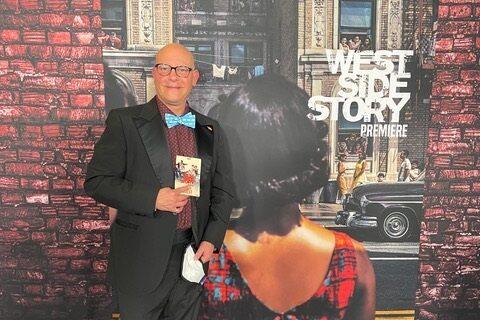

Spielberg set out to fix those flaws with his remake. Among other things, he recruited an advisory board to offer guidance on racial and cultural issues. The panel included Ernesto Acevedo-Muñoz, chair of cinema studies at the University of Colorado Boulder. He spoke recently with Colorado Matters Host Ryan Warner.

Ryan Warner: Tell me about your own interest in this musical. How far back does it go?

Ernesto Acevedo-Muñoz: As a Puerto Rican, West Side Story has always been part of my life. Some scholar once wrote, "West Side Story was a Puerto Rican 'Birth of a Nation.'" It's the movie by which we are introduced and made present in American popular culture. And with all its imperfections and its difficulties, it's been a cultural filter through which many Puerto Rican people in the United States come to be associated.

My father was a drama teacher most of his life. We went to theater, we went to movies. We had a few albums from Broadway shows and a lot of albums from movie music, and West Side Story was always part of the soundtrack of our lives. Particularly the 1961, the movie album, not the Broadway album. It was part of the soundscape of our home.

Warner: The 1961 movie did bring Puerto Rican identity to the screen. The Sharks were a Puerto Rican gang up against the Jets, who were white. But many critics view it as fatally flawed because of its representation of Puerto Ricans and Latinos in general. And of that original film there was only one Puerto Rican actor – Rita Moreno. A massive underrepresentation, would it be fair to say, in the original film?

Acevedo-Muñoz: Yes. An important underrepresentation that yet would not have been rare within the context of Hollywood film-making. The producers had hired an agency in Los Angeles that typically represented Latino actors, but most of them would not have been of Puerto Rican descent. The only Puerto Rican born in the island was Rita Moreno, and then she was surrounded by other assorted Latinos that were really in the background of the background, and by white actors in brown face which, however alarming, would have been the common practice for Hollywood at the time.

Warner: Do you remember the first time you saw the movie thinking those are actors in brown face?

Acevedo-Muñoz: Probably. I must have been a teenager. I would've remembered, but I was more impressed by the fact that I heard the words Puerto Rico spoken in a movie than I was by seeing actors in brown face, because that would have been normal.

Warner: And actors with fake accents too.

Acevedo-Muñoz: With fake accents and brown face, and not only brown face, but they all had to wear a certain makeup that made them all look the same shade of brown. It wasn't only brown face but it was the same brown face for everybody, including Rita Moreno, who is a fairly light- skinned Puerto Rican. We come in all colors, as you know.

Warner: What do you feel when you see the original movie today? Is there still a part of you that appreciates it?

Acevedo-Muñoz: Yes. Largely, and I'll tell you my 2013 book “West Side Story As Cinema,” is in part an assessment of the movie in large part in its quality as cinema, not as a sociological document or a sociological documentary. If I'm going to be interested in a movie, I have to be interested in a movie visually. And the 1961, the original, version of West Side Story is visually a stunning movie. This movie is just interesting to look at, and it also has all these other problems.

There's a section of my book with the subheading, Must We Burn West Side Story, because of the injustices that it does in the representation of not just of Latinos, but also of queer Americans. We have the character of Anybodys, who is a caricature and is one of the white kids in the show. That aside, the visual quality of the movie does not go away.

Warner: The original film version was nominated for cinematography.

Acevedo-Muñoz: It won for cinematography for sure, and production design, and costume design. All the visual elements, film editing, all the visual elements.

Warner: I so appreciate you making a distinction between the sociological aspects of a movie, documentary aspects of a movie, and the movieness, the cinematic qualities of it. In the remake of West Side Story, the neighborhood becomes a character.

Certainly the scenes of the original West Side Story were very important, but I don't recall feeling that the neighborhood was quite as much a character in the original as in this new one. Do you want to speak to that a bit?

Acevedo-Muñoz: You're right on target Ryan, because one of the commitments of the producers of the new movie was to render authenticity to the look of the neighborhood, to the sounds of the neighborhood, to the atmosphere. And in fact, some of the historical consultants that worked on the new film were specifically pointing down to things like even graffiti on the walls, wouldn't have been appropriate in the Puerto Rican barrio in 1957, to see that painting on the wall or to see that graffiti.

Warner: Well, and of course you have to think about what is happening to this neighborhood, to the neighbors, the displacement at this point, right?

Acevedo-Muñoz: Right. Which is also another matter that the original movie brushes aside. Not coincidentally what little of the 1961 movie was filmed in New York City was filmed in that stretch between West 63rd and West 68th or so, where Lincoln Center stands now, but gentrification itself is not addressed in the 1961 movie.

The new movie, the 2021 movie purposely makes gentrification part of the conflict. It gives the Jets a reason to be so angry that they are literally being displaced. It's not just that more Puerto Ricans are moving to the neighborhood, is that the neighborhood itself is disappearing.

Warner: Early on, one of the opening shots of the new film, you see that homes, tenements are about to be razed and what's going to replace it is this sparkling new performance space called Lincoln Center. So the new movie's director, Stephen Spielberg went in saying that the stereotypes needed to go, that he wanted this film to be more sensitive. And you were on this advisory committee that he created to help with that. Where does the movie still fall short?

Acevedo-Muñoz: Well, I can tell you that there will always be naysayers for some critics of West Side Story, from the perspective of sociological perspectives, also the cultural studies perspective, there will always be naysayers saying, ‘Well, look, here we go. Now, Steven Spielberg is making the Puerto Ricans dress-up and dance.’

But regardless of the naysayers, the reality is that the new production went out of its way to put together this community advisory board, as we called it, composed of historians, intellectuals, academics, artists, musicians, people from the neighborhood who were there. If we're going to do this, the mantra was, then let's do it right.

Is it going to make everybody happy? No, because some people think that West Side Story shouldn't exist to begin with. There's always going to be controversy. But if West Side Story wasn't controversial, we wouldn't be talking about it. It does have a resonance.

West Side Story has never gone away because it strikes a nerve and it strikes the nerve in part because it helps us to start a discussion about things that are still very resonant in America – social relations, race, ethnicity, gentrification, tolerance. It’s not by chance that suddenly West Side Story is relevant again.

Warner: One of the songs that has come under the most criticism is America. The lyrics to the 1957 Broadway play were viewed as especially racist. That changed some in 1961 and then again, in this iteration. Give us an example of one of the more recent changes.

Acevedo-Muñoz: The 1957 version had essentially no redeeming qualities. It was just, ‘life in Puerto Rico is terrible and we're moving to the United States to have a life of conspicuous consumption.’ All the girls talk about is going shopping and having a washing machine and things of the sort.

In 1961 that was adapted to make it much softer. So some of the most damaging lyrics, for example, about gun violence in Puerto Rico, about hunger in Puerto Rico, were substituted by somewhat softer lyrics. For example, the 1961 revised lyrics still start with Rita Moreno, as Anita, singing the lines, “Puerto Rico, my heart's devotion let it sink back in the ocean.” And that was softer than ‘57.

That's not very soft, but then the 1961 lyrics are a real argument. The girls have a position. ‘We love it here and we want to go shopping.’ And the boys have the opposite position. That was new to ‘61. The boys are, ‘terrible time in America, organized crime in America, everywhere grime in America.’ The girls say something like, ‘Here you're free to choose.’ And the boys say ‘Yes, free to wait tables and shine shoes.’ It has political bite, but it was still offensive.

The new movie gets rid completely of the specific line, ‘Puerto Rico, my heart's devotion, let it sink back in the ocean’ and it picks up much softer lyrics, ‘Puerto Rico, you lovely island …’

It's kinder to Puerto Rico. It's still an argument between the characters, but it doesn't open with burying the whole island under a pile of rubble.

Warner: The Sharks also sing in the new movie. The original version of an important Puerto Rican Anthem, right?

Acevedo-Muñoz: That is new. And it's not only the Puerto Rican anthem, it is the specific lyrics of the Puerto Rican anthem that are pro Puerto Rican independence. Most of those lyrics were written for a failed revolutionary attempt in the 19th century against Spain. That lyric would've been by law prohibited in Puerto Rico and probably in the United States, but they do sing what we refer to as the revolutionary lyrics.

Warner: By the way, is it historically accurate? I'm just curious.

Acevedo-Muñoz: The lyrics are accurate. I grew up within the independence movement, so I knew those lyrics when I was a child. Is it accurate to the 1950s context in New York? More than you would imagine.

We're looking at the mid 1950s. A large portion of the Puerto Rican independence movement had been based in New York at the time. Some of our listeners will surely remember the 1954 Puerto Rican nationalist shooting in the U.S. Congress where four Puerto Ricans went into the Congress chamber and fired shots and yelled, ‘Long live a free Puerto Rico.’ That group was based in New York. So a lot of the roots of the Puerto Rican independence movement, the president of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, had been based in New York. Considering the specific context, it would not have been out of place at all.

Warner: In the new film, 20 actors who are Puerto Rican or of Puerto Rican descent appear including Ariana DeBose, who's nominated this year for best supporting actress, and Rita Moreno who won that award for the 1961 film. Moreno is back as an entirely new character and she serves as an executive producer (of the film). Moreno has called this new film the jewel in the crown of all of the versions.

And yet, at 90, she's still angry about what happened after the first film. She says she just wasn't offered any more major roles, telling Buzzfeed, ‘Nobody gave a (bleep). It broke my heart, absolutely broke my heart.’ How do you understand what happened to her after West Side Story, the original film?

Acevedo-Muñoz: Hollywood relies on formulas. And one of the most interesting things about the character of Anita, which most of us know through Rita Moreno's performance, is that she is both a rebel and a stereotype. Anita falls in a way within what we would call the Latin spitfire. She dances, she wears flashy clothes. She talks back. She argues with her boyfriend. She's sexually active, we are led to understand in all versions of West Side Story. It takes a very versatile, a very brave, actor to take on the role of Anita and then run away with it. And Rita Moreno is a magnificent example.

Warner: But that comes with risks.

Acevedo-Muñoz: It comes with risks. And because Anita is also something of a stereotype Rita Moreno continued to be offered the Latin spitfire types, and she did not want to do that. And for the better part of the next eight years or so she had very, very few parts in movies. She just wouldn't accept the pigeonholing that comes with a part that is so iconic. And of course she was heartbroken and of course she was disappointed. Here's the best part she's ever played and if she wants to not be stereotyped, it's also an obstacle.

Warner: The new role is Valentina. She is a maternal figure, she is in many ways the conscience of the movie. Do you want to speak a little bit to the new role and whether you like the invention of it?

Acevedo-Muñoz: It's one of the things that also seems part of the effort to maximize the diversification of this cast. There's no reason why a woman like Valentina would not be running the little candy store in this rundown neighborhood anyway. The movie makes the connection that she is widow to the white man who originally owned Doc's candy and drugstore.

Warner: She's part of a mixed family, a mixed marriage.

Acevedo-Muñoz: Exactly. A mixed marriage in 1950s New York would've been rare but not impossible, and Valentina being an entrepreneur is part of the shifting cultural and social landscape of the neighborhood. But it also makes her a character that is ambiguous in some ways. She is a maternal figure mostly to the Jets, not the Sharks. Ariana DeBose, as Anita, comes in to confront Valentina. ‘You give shelter to these pigs.’ She says it in Spanish, accusing Valentina of being a traitor.

But it goes to the complexity of these characters that even a new character as Valentina, has to have a position and that position can be controversial. It can be difficult. She refers to Anita in that scene as ‘mi hija,’ which is to say ‘my daughter’ and Anita responds ‘yo no soy tu hija,’ ‘I am not your daughter.’

I'm using the lines of dialogue in Spanish because this was an important decision by the producers of this movie, that the Spanish dialogue between the Puerto Rican characters, when they were in their own element, would not be subtitled in English, which would have been in a way a further othering of these characters, making them even more others. If English speaking audiences don't get it, that's their problem. With a little bit of effort we can be a little more inclusive, culturally.

The Academy Awards will air at 6 p.m. Sunday on ABC