Pressure is mounting among Democrats in the legislature to consider increasing the penalties for possession of fentanyl, and it could result in lawmakers walking back part of a 2019 drug law.

Last month, a bipartisan group of lawmakers — including the Democratic Speaker of the House — introduced a fentanyl “accountability and prevention” bill that was meant to respond to rising use and overdose deaths from the drug.

The bill focuses its punitive efforts mainly on tougher consequences for dealers, saying they didn’t want to excessively punish addicts. But some law-enforcement leaders, including Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen, argue that doesn’t go far enough, and more people should face felony charges for simply possessing fentanyl.

Now some Democratic lawmakers have joined the push for that approach.

“I think we need to be giving law enforcement whatever tools are necessary to get people to those programs so that they might survive. What we're doing right now is just going to lead to more and more death,” said state Rep. Alex Valdez, a Democrat and potential candidate for Denver mayor who supports harsher penalties for possession.

Valdez is not closely involved in negotiations over the bill, but that message is gaining traction among some House Democrats ahead of its first committee hearing next Tuesday, and House Speaker Alec Garnett is reportedly weighing arguments for harsher penalties. That could include an amendment to be presented before the House Judiciary Committee next week.

State Rep. Kerry Tipper, vice-chair of the committee, said she wasn’t sure what would be presented. “Between now and then, it’s an eternity in legislative time,” she said.

2019 law at heart of possession debate

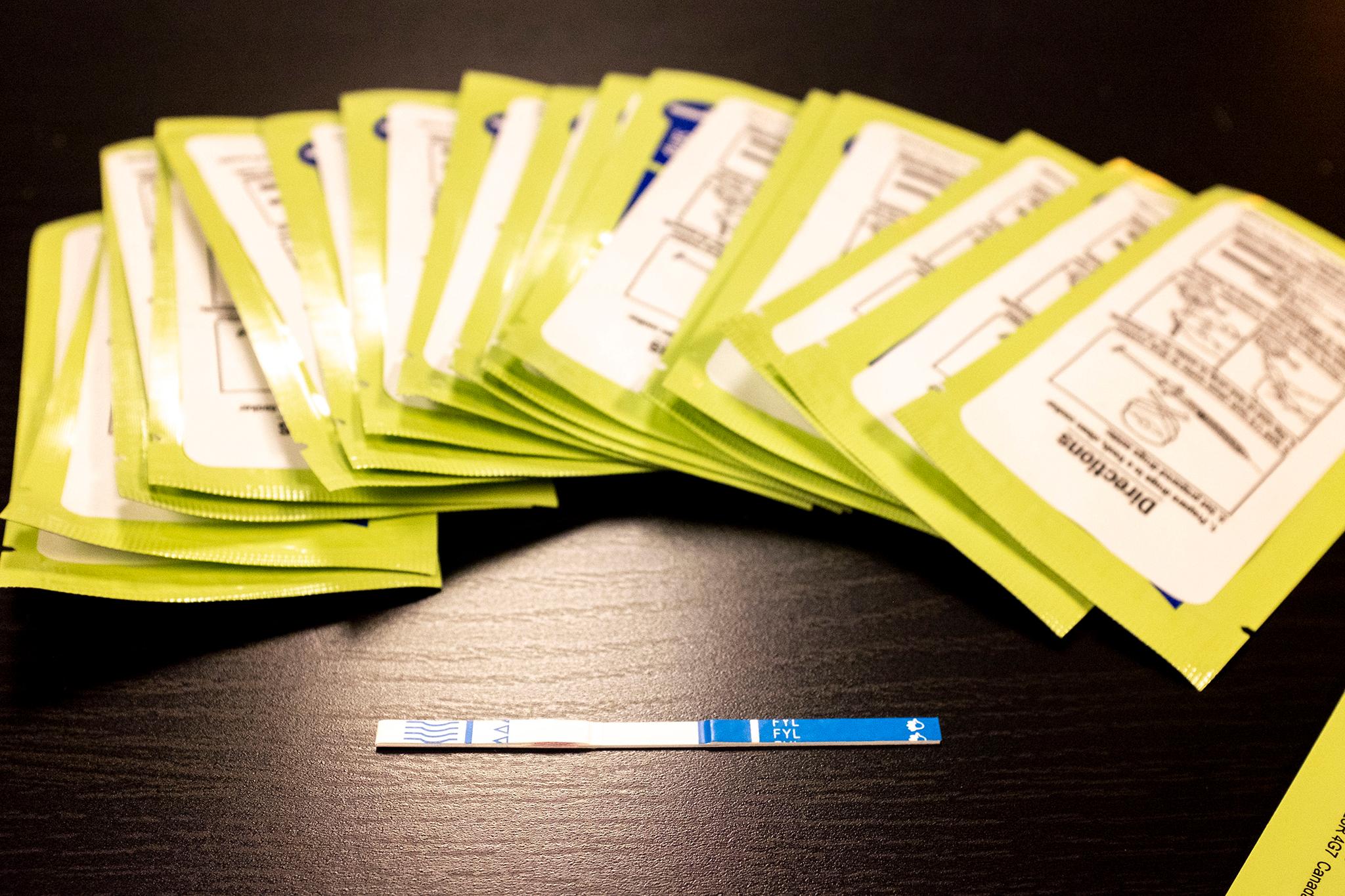

Until 2019, possession of any amount of opiate drugs like fentanyl was a felony. Then, a new bipartisan law reduced penalties for drug possession in general: People with less than 4 grams of most drugs, from MDMA and mushrooms to pills laced with fentanyl, would face a misdemeanor instead of a felony, unless there was evidence they were dealing the drug.

Denver chief Pazen said that some dealers are taking advantage of the new law, carrying just less than four grams of fentanyl-laced pills to avoid felony possession charges. They still could be charged with a felony for intent to distribute for lower amounts of fentanyl, though that may be harder to prove for police and prosecutors.

Law enforcement officials have also argued that prosecutors can use the threat of a felony to push people into treatment instead of prison — leverage they say they lost with the 2019 law.

A drug misdemeanor — the current penalty for possession under 4 grams — can result in jail, probation or fines. If a judge chooses jail, the maximum sentence is 18 months, but the result is most often probation, said criminal defense attorney H. Michael Steinberg.

In contrast, a low-level drug felony can result in a sentence of probation, community corrections, or incarceration. These charges often result in prison time — an average of about 5 months served, plus 10 months probation — and bring with them the other serious consequences that result from a felony.

“A felony conviction in our society is considered much more serious than a misdemeanor,” Steinberg said. Felonies can be particularly problematic in a job search, for example. “It’s a very, very different world in the felony world.”

Competing amendments under debate

Sources said two different amendments are being discussed behind the scenes. One would lower the felony threshold from four grams to two. Another other option would make possession of any amount of fentanyl a felony.

Drug weight limits apply to “compound mixtures,” meaning that someone could cross the limit if they have several grams worth of pills that contain only trace amounts of fentanyl.

The potential turn toward harsher penalties has some Democrats concerned about a return to the war on drugs.

“I am personally not inclined to repeat what we did 30 years ago,” said state Rep. Jennifer Bacon, a Democrat and criminal justice reformer. “We spent 30 years trying to undo the tangle that was crack and cocaine. We spent 30 years trying to say we're spending way too much incarcerating people and not educating kids.”

She suggested that if the goal is to get more people into treatment, the state needs to make treatment more widely available and get rid of waitlists.

House Speaker Garnett, who is shepherding the bill, did not respond to a request for comment. He’s engaged in fast-moving negotiations about whether to amend the bill, statehouse sources said. Most have been unwilling to go on the record for fear of drawing leadership’s ire.

State Rep. Kyle Mullica, the Democratic co-whip, said that the party needed to listen to law enforcement concerns about possession penalties.

“I appreciate the leadership that the Speaker’s shown on this, to really address this issue, but I also think that we need to really get that buy-in from our law enforcement and our district attorneys making sure that we're truly addressing this problem, giving them the tools to address it and making sure that we have an avenue for individuals to get the help that they need as well,” Mullica said.

The House Judiciary Committee is scheduled to hear the bill on April 12.

CPR’s Allison Sherry contributed to this report.