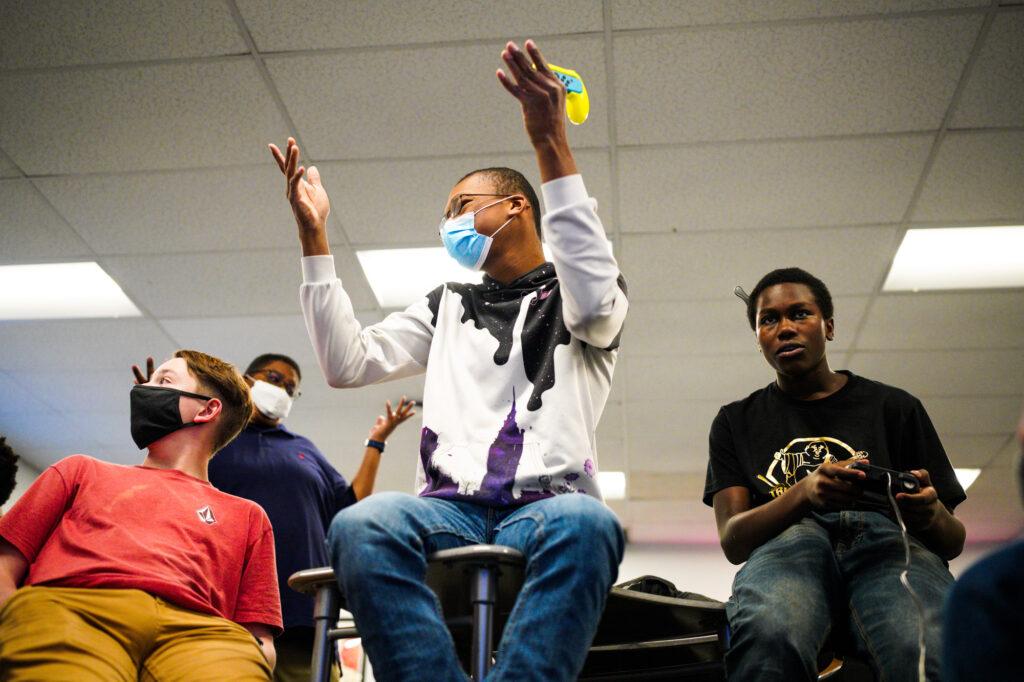

Mariana Marquez is a typical high school athlete. She practices with her team, meets with coaches and shows up for game day to compete against other high schoolers.

But unlike a varsity football player, her game isn’t on the turf. It’s in front of a screen.

Marquez is an esports player for Harrison High School in Colorado Springs.

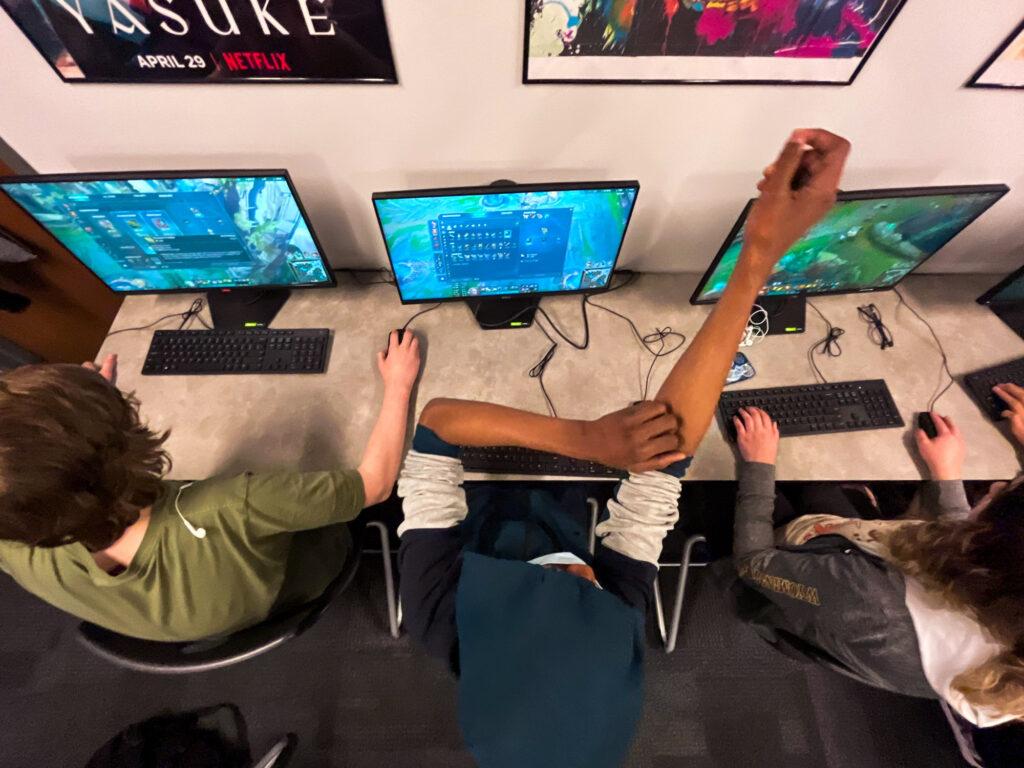

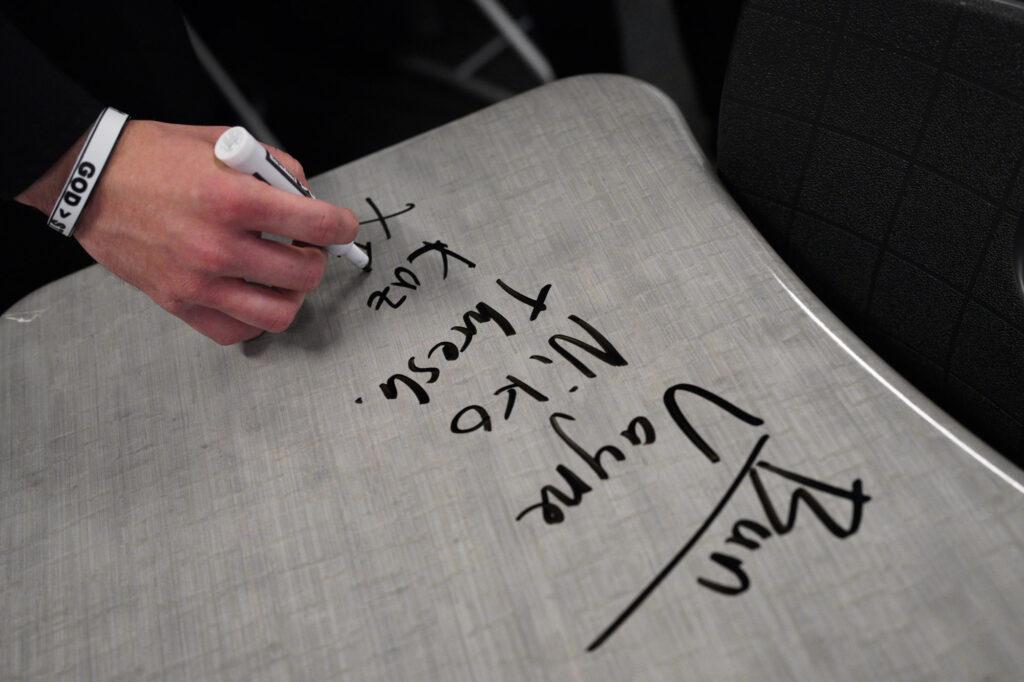

“I play League of Legends,” she said. “It's five versus five, and everyone has different roles. You can either win by [completing an] objective or they can forfeit. It's tower defense.”

The growing popularity of esports gaming has fueled dozens of professional leagues across the globe. Revenue-wise, the industry is exceeding expectations, with figures crossing the ten-figure threshold in 2020, according to some reports. And it may soon be legitimized on the world’s biggest sporting stage, with the International Olympic Committee hiring someone to lead its foray into virtual sports.

The state’s high school athletics authority has ambitious plans to expand esports into half of Colorado high schools. Rashaan Davis, who oversees esports for the Colorado High School Activities Association, said this year’s season is the busiest yet.

“There are over 100 teams playing multiple titles across our state,” Davis said. “We offer League of Legends, Rocket League, Madden and [Super Smash Bros. Ultimate].”

A much-needed support system for students

Gamers have traditionally been labeled as socially awkward geeks. Harrison High coaches Tom McCartney and Sean Hart want to break that stigma. When they were in high school, they found comfort in video games, but schools didn’t tolerate gaming on school grounds, much less encourage it.

As teachers, and now coaches, they want to foster a safe environment for those awkward geeks to develop and build their talents.

“Those are the people who ended up being the entrepreneurs, the vanguards for new ideas and opportunities and waves,” McCartney, an English and Drama teacher said. “Let's build their confidence now, so they don't have to wait until 33 or 34 when they find themselves and accept themselves to finally get started with building a new world.”

For many students at Bear Creek High School in Lakewood, the esports team is their only extracurricular activity. It’s an outlet that would not exist without the support of their school.

Seth Milota, a senior at Bear Creek who plays Super Smash Bros., said he was inspired to create the team because of the good memories he had of playing with his old classmates in Illinois. He said he approached his assistant principal with a pitch.

“He's like, ‘I really want you to make one. I've been wanting one for a while and no one's really stepped up,’’ Milota said. “So I pretty much got to work.”

Daniel Pham plays League of Legends for Bear Creek but isn’t competing this year because they couldn’t put together a full five-player team. Despite that, he’s still active in the team’s Discord, a communication app popular in gaming communities, for the social aspect.

“Without eSports, I wouldn't have friends that already graduated and went to college,” Pham said. “There's other seniors and juniors and different types of people that I'd never met in my school.”

Esports can help lead students to future careers

While the main goal of expanding esports in the state is to offer students opportunities to thrive, there is an added benefit: resume material.

For professional esports players competing in the Overwatch League, one of the more competitive and well-established leagues in the world, players earned an average base salary of $106,000.

However, that level of play is unattainable for a vast majority of amateur players. A more realistic goal for high schoolers is playing at the collegiate level. Some universities recruit and offer partial scholarships to players. Notably, Harrisburg University in Pennsylvania offered full rides to its entire esports roster in 2018.

“I wanna go into a college that has several different opportunities, if I'm able to play something I really enjoy and get an education at the same time,” Marquez said.

Even if players don’t go to a university with a team, the skills they learned through esports — like building computers, communication, and even gaming itself — can help students build future careers.

“One of the possible careers I'm going to is game design,” Milota said, who wants to develop a fighting game. “When you understand a game down to its core mechanics, its frame data, its little tiny integrations, you can get such a feeling for how the developers made it and you can take little stylistic choices and integrate them yourself.”

Accessibility is a concern

A major issue for schools is providing equipment for students to play. With hardware ranging anywhere from a couple hundred dollars to over $1,000 for a solid gaming computer, students and schools in lower-income communities have an inherent disadvantage to other esports teams. In some schools, the only students able to compete are those whose parents can afford to buy them what they need.

Harrison High’s coaches said they were only able to get the team off the ground by donating their own equipment to players.

“It was an uphill battle trying to justify, ‘Hey, why do we need game computers? Can't they use their little Chromebooks that they have?’ It's like, no, the technology needs to be these specific specifications,” Hart said. “The harsh reality of it is if we hadn't provided those things from our own homes, we wouldn't be able to compete in some of these games.”

There are limited solutions outside asking school districts to fund esports. PlayVersus, the platform CHSAA uses to organize esports, have consoles available for schools with an economic need, but inventory is tight.

Another issue coaches and teams struggle with is fostering an environment where girls are welcome. Marquez, the only female on Harrison’s League of Legends team, said even though she feels supported on the team, she thinks girls still feel a stigma around playing video games.

“I grew up in this household where my brothers were allowed to play video games and I wasn't because I'm a woman,” Marquez said.

Some teams’ rosters are completely made up of boys. Jessica Salazar, the esports coach at Bear Creek High School, said part of the struggle is helping teenagers navigate the perilous world of hormones.

“Last year we had [a girl] on the Rocket League team and there was some drama with all the boys liking her,” Salazar said. “And so she didn't come back.”

There are other hurdles state officials, coaches and students will have to face as the sport grows. But these aren’t impassable — Colorado is all in on esports, so CHSAA officials hope they’re just growing pains.