Mauricio Vargas works in electrical construction. He’s helping build a new tower on the Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

The other day he looked at the building and imagined his daughter working there — as a doctor.

“She’s always wanted to be a doctor,” he said.

His daughter, Citlalli, is only 6 years old, but that’s been her dream since she was a toddler. Vargas’ wife, Elizabeth Rivas, wonders whether that can become a reality in the school district that serves Commerce City, where they live.

“I want my children to have all the available opportunities … it’s not right that because we live in Commerce City, because it’s a poor community, it limits them,” she said in Spanish, as she cried. “Because all children deserve all the opportunities, whether it’s in Commerce city, or Cherry Creek, Boulder, it should be the same for all of them.”

Rivas and other Commerce City families are nervously awaiting a decision Thursday that will determine the fate of Adams 14.

The school district has received failing ratings from the state board for more than a decade.

On Thursday the board will hear evidence from the district, the state, and a state review panel that recommended closing Adams City High School and reorganizing the district.

The panel cited a lack of leadership capacity and stability, declining enrollment — 34 percent of Adams 14 students chose to attend school in another district last year — as evidence the district needs “drastic change.”

"Among the gravest concerns are the reported culture of fear and retaliation, the lack of sound financial and human resource practices, and the overall limited improvement in student achievement and growth over many years," the report states.

Among the options the state board is considering? Closing some schools, hiring an outside manager, converting some of the schools into charter or innovation schools or even dissolving the district.

Eighty-five percent of Adams 14 students live in poverty. It has the highest percentage of English language learners in the state. In 2019, the working-class district became the first ordered by the state to be run by an outside manager, MGT Consulting. The partnership turned rocky, and after two years and more than $8 million dollars, there was only slight improvement.

Worries and frustrations

Parent Maria Estrada says it’s been years since she’s seen academic progress in the district. She said her 7-year-old son is a slow learner, and she’s requested help several times at his school Hanson Elementary.

“There hasn’t been extra tutoring or help,” she said in Spanish. “I’ve told them that he needs more support, but no, at the moment there’s no support. But why is there support for gifted children? That worries me.”

She also worries about the turmoil at the high school. The outside review panel’s recommendation to close the district’s only comprehensive high school has thrown parents and students into a state of panic. Still, Estrada is disturbed by what she describes as a chaotic environment at the school. She said there’s too many students and not enough support.

“’Mom,’ my daughter says, ‘why go to school if the teachers tell us the work is on the computer, just do it, finish it, and turn it in.’ I ask her, well, ‘who is teaching you, who explains it to you?’”

Her daughter said the teacher told her she didn’t have time to help her. She said it feels like some teachers have given up, and her daughter isn’t getting the help she needs. Her frustration led her to enroll her daughter in a Denver high school for next year. But she’s not sure closing the high school is the answer.

“It’s going to affect my family and lots of families here in Commerce City,” she said. Many families don’t have a way to drive their children to schools in other districts, and many high schoolers take care of younger brothers and sisters after school.

Her daughter Ahylin, a freshman, said the review panel’s recommendation to close the school hit kids hard emotionally.

“When news got out students were freaking out,” she said. “The teachers were trying to calm them down, (saying) it’s possible that if the school gets shut down they’re going to make sure that every student is in a school, they’re not just going to leave them by themselves with no support.”

Adams City High leaders said they’re hard at work on improving instruction, monitoring performance and introducing more career tracks. Student motivation is a challenge, they said, with many students needing to work to help support their families.

“Our Adams City leaders and other secondary stakeholders will soon start to move our work forward to rethink and redesign what the high school experience looks like in Adams 14,” said Samuel J. Schneider, executive director of secondary education.

How did Adams 14 get to this point

Adams 14 has struggled with low academic performance for many years. Performance is measured by state standardized tests, academic growth over a year, and dropout and graduation rates. It has received the two lowest ratings from the state since 2010.

About eight out of 10 students in Adams 14 are not reading at grade level. Even fewer are performing math at grade level. Four-year graduation rates are approximately 15 percentage points lower than the statewide average. Enrollment has dropped 17 percent over the last five years. Schools or districts that don’t meet performance expectations on the state’s report card are assigned a five-year improvement plan on the state’s accountability clock. If a school or district doesn’t improve, the state board may take additional actions. At hearings in 2017 and 2018, the state board ordered an external manager to oversee the district. After more than two years under MGT Consulting, the district improved only slightly.

The state board directed an independent review panel to visit school sites and meet with district officials. In March, that review panel recommended closing the high school and potentially reorganizing the rest of the district.

On Thursday morning, the state board of education will consider a new improvement plan for the district — and, in the afternoon, separately, a new plan for one of its schools, Central Elementary. They’ll consider evidence from state education officials, the state review panel, the district’s plan and public feedback.

Parents say they feel ignored

Families in Commerce City like Maria Estrada’s have their own ideas about what should happen — but they feel ignored.

“They’re not listening to us … they’re not communicating with us. Many parents have no idea what’s going to happen with the high school or that the district is in revision.”

For Estrada’s two younger kids, she knows she doesn’t want the state to turn schools into charter schools — that’s one the state’s options, but the review panel didn’t recommend that option. Her daughter previously attended one that’s already in the district.

“Yes, it had a high academic level but what we didn’t like was they wouldn’t let the kids talk Spanish, even informally. They always had lots of homework … it was stressful and left her very frustrated,” she said. “There never was time to rest.”

‘Fight for the common good, for the good of our children’

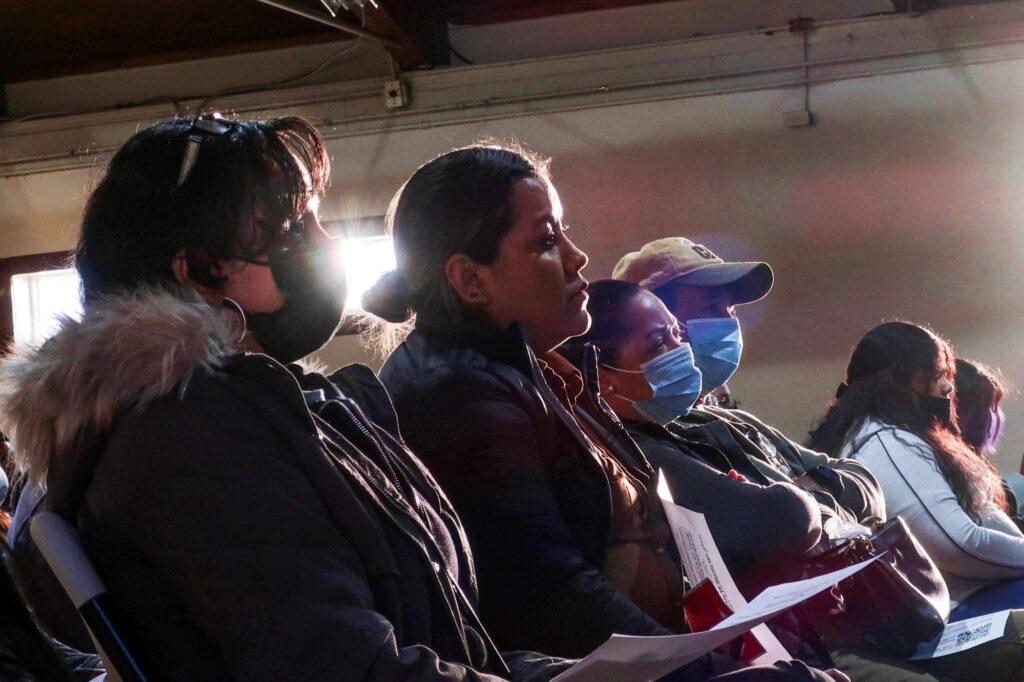

At a packed meeting at Our Lady Mother of the Church last week, mothers held babies and families bowed their heads as the local priest asked for strength to “fight for the common good, for the good of our children, for our future as a community.”

Hosted by the community group Together Colorado, the meeting was a chance for families to ask for what they want: that the locally elected school board and the new superintendent Karla Loria, who they say has experience turning around schools, be given a chance to do so.

Parent Ana Cabrera said she knows that the district has many challenges and problems to solve. But she has full confidence the district has the skills to craft a locally controlled solution to benefit all families and students.

“I have the confidence that the people elected by our community have the capacity to manage and build a district for our children that provides them with a quality education in a united environment,” she said to cheers and applause.

“A community without schools isn’t a community,” added parent Reyna Soria. Parents acknowledge there is some division in the community but they have faith in the new superintendent that things will get better.

District wants to steer improvement plan

District leadership and the local Adams 14 school board has indicated it doesn’t want to be managed by an outside partner.

“We hope the board realizes the experiment (MGT Consulting) done in the community didn’t work,” said district spokesperson Robert Lundin. “An outright manager, the research shows, doesn’t transform outcomes, and in our case $8.5 million dollar later, we didn’t see it making a positive impact.”

Instead, the district proposes a “partner manager” that emphasizes “partner, ” with Superintendent Karla Loria and the local board maintaining authority over the district. One applicant is TNTP, a nonprofit focused on improving K-12 education, which has worked in many districts with demographics similar to Adams 14. The district has conducted several community meetings with TNTP officials. More details on the district’s proposal were submitted to the state board of education for Thursday’s hearing.

Parents support the district’s proposal to turn the district’s Central Elementary school — also on the state’s watch list — into a community school. That’s a school that has a lot of social services families can access in addition to academics. Parent Elizabeth Rivas said that the board needs to understand that there are many social and family issues that can be barriers to learning.

“This is a poor community and community schools focus on families, what they and students need beyond academics … for example, mental health is something that if students get that help, they’ll be able to focus on their studies.”

Central’s plan also includes more learning time on core subjects and after-school programming. Rivas worries the state isn’t looking hard enough for a solution that reflects the unique needs of students and families in Commerce City. State officials' threats to close schools or dissolve the district can be traumatizing.

“Instead of helping, it is harming,” Rivas said. “Their duty is to help the community. The schools are public. They’re made for the community so they have to listen to the community. They can’t make a decision just because they believe it’s the best without taking into account what parents and students want.”

Many parents are also skeptical that standardized test scores are an accurate reflection of what a child knows. They point to the fact that many children may be taking the test in their second language.

“Our children are brilliant children,” Rivas said. “All children are different. And the state needs to see that. And to try to understand us and help our students and schools and bring the necessary programs to our children. The tests don’t reflect everything our children know.”