On a brisk Friday morning last month, Colorado Springs resident Kathy Zilverberg joined a few of her friends for a walk through the Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument. The women call themselves the SLOTHs, or Slow Ladies On The Hike, and for their weekly strolls they search for scenic trails with gentle grades. The monument certainly fits that bill.

Also, Zilverberg suspected there would be plenty of parking — and she was right. The monument’s lot was nearly empty, save for the cars the SLOTHs themselves drove.

That’s nothing terribly unusual for visitors to find at the fossil beds, located about an hour west of Colorado Springs. And even during the height of the pandemic, just as many of the state’s public lands were swarming with residents looking to escape COVID-19 lockdowns and canceled indoor events, the monument remained relatively quiet.

“Certainly we’re being loved, but I wouldn’t say we’re being loved to death,” said Florissant’s lead interpretive ranger, Jeff Wolin.

Wolin said he received emails during the pandemic from visitors saying they relished the monument’s 15 miles of trails as a place they could go to escape the crowds they were seeing elsewhere in the state.

Colorado Wonders

Despite being a fourth-generation Coloradan, 75-year-old Karen Michalak of Elizabeth, Colorado, still wasn’t sure exactly what the fossil beds were when she recently wrote in for our series Colorado Wonders.

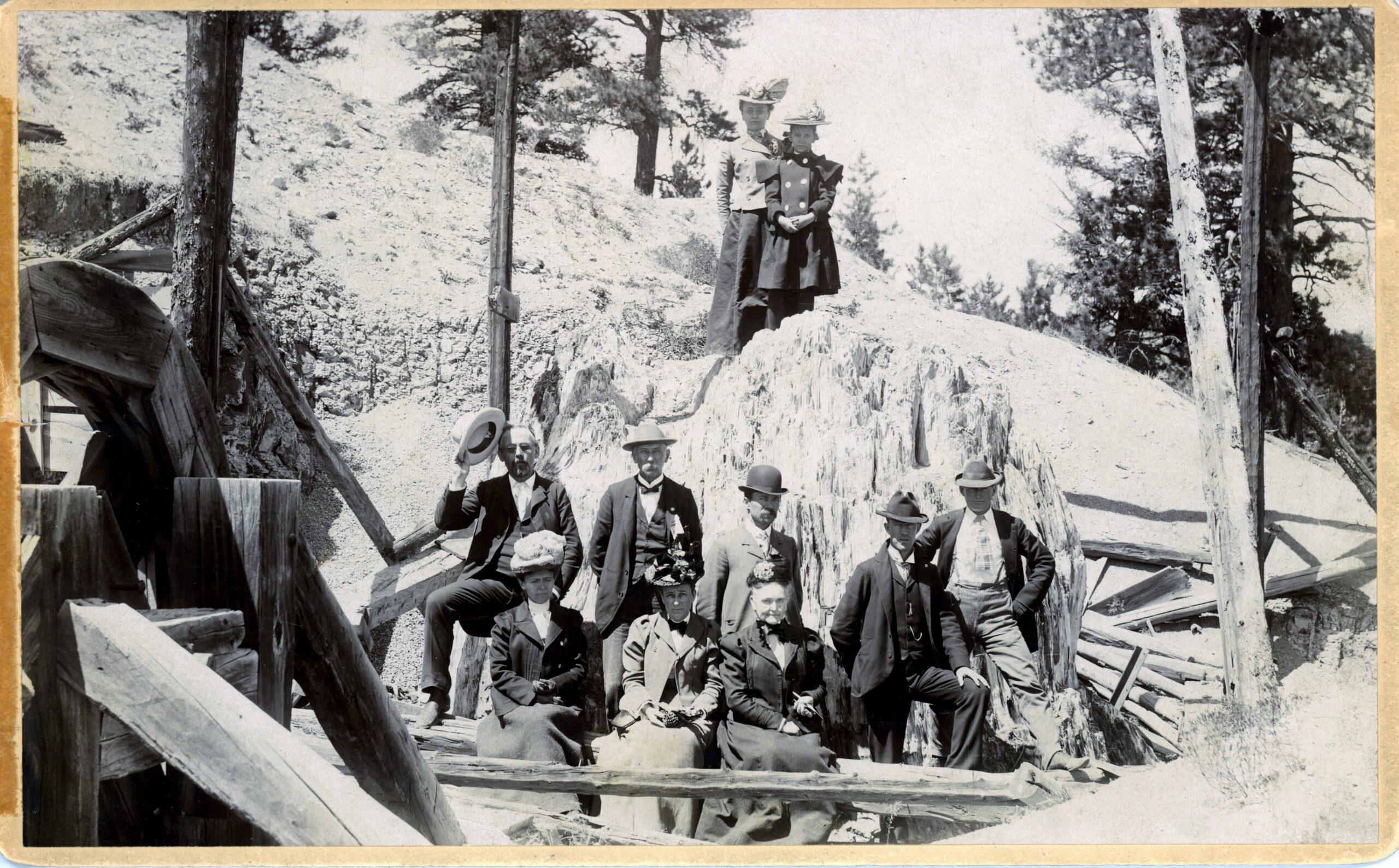

“I’ve seen a couple of interesting photographs from back in the early 1900s that my family handed down about this place called Florissant, and I’ve never been there and I’m just very curious about what is there and what it’s all about,” Michalak said.

In particular, Michalak said she was curious about the enormous petrified tree stumps she saw in her family photos. How were they formed, and when?

Wolin said it does often seem odd to people when they see the stumps of huge redwood trees in Colorado; it’s a species that today is mostly isolated to California and Oregon. But 34 million years ago, redwoods — some up to 14 feet across in Florissant — were common across much of the Northern Hemisphere, due to the generally warmer and more temperate climate found here at the time.

This time period, known as the late Eocene, also saw a much more volcanically active Colorado than modern times.

So just how did Florissant’s trees become petrified? Successive nearby eruptions buried the land containing the monument in layers of ash-laden mud, creating ideal conditions for what is now one of the richest and most diverse fossil deposits in the world. The mud buried the trees and over time petrified them up to a certain point up their trunks. Over time, the mud and its chemical make up basically turned the stumps into stone. Scientists at the monument say about 30 stumps have been discovered so far, and it’s possible more may lay beneath the surface.

Under the radar

When asked about being a ranger at one of the National Park Services’ quieter locations, Wolin was bullish in his pride.

“I’ve been here for 20 years, if that says something. I love this place,” Wolin said. “There’s always something new.”

Indeed, Wolin said researchers using new technologies are still finding rich new fossil discoveries on the monument grounds.

He said the paved walking path around the visitors center and the main collection of petrified stumps does tend to feel crowded in summer months, but that even then solace can be found on the monument’s trails farther afield.

Last year, Wolin said just 71,000 people visited Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument. To compare, 2021 visitation to Rocky Mountain National Park was 4.4 million.