A schizophrenic man had opened fire on a packed movie theater in Aurora, killing 12 and injuring dozens more.

Something had to be done.

The Aurora theater shooter had tried to get mental health treatment before the killings. That provided a possible opening for then-Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper to search for preventive solutions. He turned to his cabinet and asked for a plan to expand crisis mental health services. He got a comprehensive blueprint to spend millions more, but it came with strings attached: To get the money, the system might have to change.

“If you keep putting more money into that system, you're likely to get more of the same result,” said Reggie Bicha, former head of the Colorado Department of Human Services. “And we felt as a leadership team at CDHS, and the governor's team supported this, that we needed some new ideas and new perspectives, and we wanted these new dollars to go out in a competitive array.”

Ultimately, that didn’t happen.

As Colorado embarks on a new attempt to reform the delivery network for mental health care in the state, the events of 2014 offer a look at how difficult it can be to impose change on the politically connected, deeply-entrenched group of community-based providers that have managed the system for decades.

That year, everyone from the governor to the head of the state Department of Human Services and legislative leaders announced their intention to change the system and increase access to psychiatric care for poor Coloradans in crisis.

But after a bid was awarded to a new provider with an innovative plan, the state reversed course, sweeping aside their declared desire for reform and challenging their own bid procedures. Then, when the winning bidder also won in court, the current providers stepped in, settling the case, tightening their hold on mental health treatment in the state and seemingly permanently eliminating the biggest threat to their dominance they had ever faced.

Experts at the state who had long worked for change were crushed.

“That was the most difficult, probably, time in my career I've ever had,” said Chris Habgood, a former staffer at the state Department of Human Services who wrote the plan for change in the 2014 effort. “Because when you know you’re doing something that is the right thing to do, to help people, you're so excited about creating this new system that will help Coloradans.

“And then all of a sudden it comes to a crashing halt because the service delivery system didn't like what the outcome was … there's winners and losers, and the losers didn't like losing and they were gonna make sure that they were not the losers.”

In partnership with COLab and news organizations across the state, CPR News has spent months examining how Colorado’s system for treating people who are both poor and mentally ill came to be, and how it has survived challenges to its structure.

Previous stories from the consortium have shown how some of the state’s 17 community-based mental health providers have failed to provide treatment to the toughest and most expensive cases while avoiding competition.

And while the companies point out that thousands of people are helped through the system each year, studies have shown that Colorado has the highest rate of adult mental illness in the nation and one of the lowest rates of access to care.

George DelGrosso, who in 2014 oversaw the Colorado Behavioral Health Council, the lobbying group that represents the existing providers, did not return multiple messages seeking comment. Doyle Forrestal, who took over from DelGrosso as head of the CBHC in 2015, said she believes the terms of the 2014 settlement preclude her from commenting on it. She declined an interview, and claimed it was unlawful to discuss details of the centers’ secret agreement to stifle the competitor.

The current head of the Jefferson Center for Mental Health, which was among the centers that drove the settlement, noted that it happened under previous leadership, and questioned why CPR News and COLab were continuing to examine the performance and history of the current providers.

“It seems there exists an intent to harm the integrity and reputation of community mental health centers, at a time when it is critical that we remain available to thousands of people in our community who need and trust the care we provide,” wrote Kiara Kuenzler, president and CEO of the Jefferson Center for Mental Health, in an email to CPR News. “Jefferson Center serves more than 25,000 people each year, and CMHCs serve more than 200,000 people across Colorado each year.”

“We have a duty…”

On Dec. 18. 2012, five months after the Aurora theater shooting and on the eve of the state legislative session, Hickenlooper stood in front of the media and announced the plan to revamp mental health treatment in the state.

“We have a duty to look at how we help each other,” said Hickenlooper. “I believe these policies will reduce the probability of bad things happening to good people.”

The news caught the attention of David Covington, an executive at a behavioral health company in Phoenix, AZ.

“This was a national story,” Covington told a Denver District Court judge in 2014, according to court recordings obtained by CPR News. Covington testified that Hickenlooper and his team “really wanted cutting edge. They were seeking innovation. They wanted community collaboration in a way that they hadn't seen before. I think that was what really attracted us to this opportunity.”

Covington had spent a career in mental health services, starting as a licensed counselor, working his way up to an executive role with Magellan Health Services, which had the contract to serve Maricopa County, covering Phoenix. At one point they served 100,000 active clients in the county.

But Covington, after hearing news of what Hickenlooper wanted to do, decided Colorado would be his new home.

“We thought this is where the country’s going,” said Covington. “This is what people will be looking at. So we wanted to bring the A-team to that.”

That would first require some gymnastics on Covington’s part. Habgood said that in response to the lobbying by the existing providers as the new legislation worked its way through the General Assembly in 2013, the state would be restricted to selecting only a Colorado-based company to provide the crisis services called for and funded in the new bill.

So Covington testified he tapped the best in mental health crisis services across the country and together formed a Colorado company called Crisis Access of Colorado. He tendered his resignation from the Arizona company, so his resume could be added to the proposal to Colorado.

His gamble paid off.

On Oct. 16, 2013, Colorado informed Covington that Crisis Access had won the bid.

In an internal letter at the Colorado Department of Human Services, Habgood wrote to the head of procurement, “the Committee found Crisis Access of Colorado’s proposals to be the most innovative, integrated and recovery-focused proposals for transforming Colorado crisis delivery across the state.”

A secrecy provision binds the parties from the 2014 suit, and Covington said he could not comment. But he told the court that he wasted little time.

“Immediately we were on the ground here,” Covington testified. “I was looking at houses to move here, looking at schools, beginning to craft out how we would engage employees in the hiring of 150 to 200 plus staff here in Colorado.”

Two weeks later the euphoria of the notice of award of contract would come crashing down. Covington was told first that the request for proposals process was under investigation by the state, and within weeks he was informed he would not get the contract, that the program would go out to bid again.

He was also informed that his competitors - the state’s existing centers - got a copy of his full proposal, but he couldn’t get a copy of theirs.

“It was very frustrating,” testified Covington. “We had carefully thought out what we hoped would be a winning strategy, and put together companies, took their unique product lines and melded them into something that had never been done before.

“And that competitive advantage was now available to entities that had finished second to us in those four regions. So it felt like our competitive advantage was completely eliminated by what seemed like a very unfair process.”

So Covington sued the Colorado Department of Human Services to stop another bid process. What resulted, according to testimony reviewed by CPR News, was a bizarre alignment of shifting interests in which the same state agency that wanted competitive bidding argued that its own process was flawed. At the same time, the state’s existing centers that lost the bid functioned as shadow defendants unnamed in the suit, but supporting the state’s legal strategy. Ultimately they settled the case themselves in the secret agreement.

“Getting so much pressure from the Governor's office”

Almost from the moment the legislature voted to require the new program to be competitively bid, there was concern at the state about the reaction of the existing centers, represented by the Colorado Behavioral Health Council, CBHC, and its powerful leader, George DelGrosso.

Shortly after the state announced Covington’s company won the bid, an email came into Habgood’s inbox from his boss Patrick Fox, who wrote, “Who is going to talk to George?”

The losing bidders made up DelGrosso’s board, representing centers from every corner of the state: AspenPoint (now Diversus Health), Community Crisis Connection (a group comprised of the metro area centers), Northeast Behavioral, and an affiliate of Mind Springs.

Harriet Hall, who ran the Jefferson Center for Mental Health at the time and was part of the Community Crisis Connection group that bid on the crisis program sent an email to supporters, saying “We are exploring all legal options for review of the awards process…”

At stake was a crisis program that at the time was projected to add about $45 million in new money for services, just for the first two years. But beyond that, the entry of Covington's new company into a market that had been controlled by the community-based centers for decades promised to disrupt the delivery of mental health care in Colorado in new and unpredictable ways.

Emails entered as evidence along with testimony in Covington's suit indicate that the groups used their web of political connections to put pressure on the Department of Human Services and the governor’s office to kill Covington’s innovative proposal, according to Covington’s attorneys.

The leader of Human Services at the time, Bicha, quickly ordered a review of the RFP process by a separate state agency, the Department of Personnel and Administration. The agency produced a short, one page summary of its findings, which CDHS relied upon to cancel the bid award, according to evidence presented in court.

The Denver District Court judge found the summary to be “trumped up” by the state in a deliberate effort to overturn the bid. The full DPA investigation wasn’t delivered to Bicha until after the RFP was invalidated.

Covington’s lawyer, Todd Miller, relying on email evidence, provided his theory to a Denver judge of why the department did that.

Leadership at CDHS were “getting so much pressure from the Governor's office, that all they wanted was some cosmetic cover, which they thought they had in that one page summary to cancel.”

People who had been a part of scoring the bids were surprised when there were suddenly concerns.

Chris Olson, then the executive director of the County Sheriffs of Colorado was on the RFP committee. Law enforcement officials tracked the process closely because, until that point, deputies and police officers had often been responsible for dealing with and transporting people undergoing mental health crises. He remembers an interview he did with state investigators from DPA.

“Gave them pretty much what I'm telling you right now,” said Olson in an interview. “That I thought it was a fair process and that we were not motivated politically on this. And, yeah, the out-of-state firm got it. I mean, there's nothing wrong with that. That's just, they won the bid.”

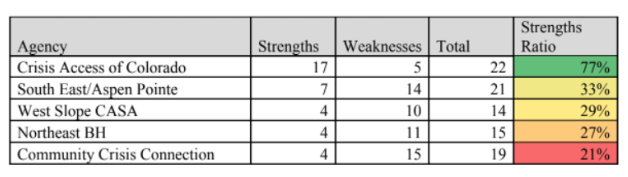

Despite the lopsided scores in favor of Crisis Access of Colorado, David Covington’s company, and despite the participants in the RFP committee at the state feeling that it was clearly a fair process, leadership at CDHS canceled the RFP and announced they were putting it out for bid again.

The existing centers declared victory, sending out an email thanking supporters for putting on the pressure. Harriet Hall, at the Jefferson Center for Mental Health, wrote: “I know that many of you expressed your concern to CDHS and/or the Governor’s office, and I want to thank you for this. I believe that the concerns expressed by many of you and the strong community support were vital to this solution.”

Though the additional funding and creation of a new system for delivering crisis mental health services was a signature initiative for Hickenlooper, those who ran his office said they couldn’t recall much, if anything, about how the 2014 effort unraveled.

In an interview, Roxane White, Gov. Hickenlooper’s chief of staff at the time couldn’t recall anything about the episode.

She suggested reaching out to Hickenlooper’s then-chief strategy officer, Alan Salazar, who is now chief of staff to the Denver mayor. Salazar also couldn’t recall anything about the crisis services controversy. He suggested Katherine Blair Mulready, who was a health care specialist in Hickenlooper’s office.

“I remember that the original bid was given to an out-of-state entity without an existing footprint in Colorado,” said Mulready, in an email. “And that when that was announced, the community mental health centers were very upset. While I don’t remember any specific conversations on this topic, I spoke with leadership of CBHC – the trade association for the CMHCs/BHOs – frequently during my tenure in the Gov’s Office (2011-2014), and the issue may have come up in discussions with them.”

Pressure was intense from the state legislature too. Then-state senator Irene Aguilar who sponsored the law that directed money to the program sent emails that made their way to the Department of Human Services that were described in testimony as pointed. It’s unknown exactly what she said, but it was revealed in court that it helped prompt specific inquiries in the internal review. Aguilar did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Her emails were introduced as exhibits but are no longer in the court file.

In court, Covington’s lawyers focused on the impact of Aguilar’s concerns, which were forwarded down the chain of command at CDHS to Clint Woodruff, lead of the Division of Financial Services, who officially initiated the DPA review and ultimately invalidated the bid.

“Particularly Senator Aguilar's email,” said Todd Miller, Covington’s lawyer in closing arguments on the preliminary injunction. “That very day, all of a sudden, we get a notice that the DPA is going to be asked to review this thing, and an email that says ‘Clint, be sure when the DPA looks at this, they take care of Senator Aguilar's concerns.’”

In an interview, Woodruff denied there were any political motivations behind invalidating the bid. “I was asked to do a review just because it was a lot of money,” said Woodruff. “It was a very significant bill, right?”

Woodruff said that the request to review the bid came from his boss at the time Susan Beckman, and he maintains that there were fatal flaws in the process and the bid deserved to be invalidated.

Multiple messages left at phones listed as belonging to Beckman were not returned.

Emails also came from Dean Toda, who handled media for the State House Democrats at the time, checking on the status of the bid.

CPR attempted to obtain copies of the emails, but the exhibits could not be located by the court.

“a manufactured reason”

After listening to testimony over four days in early 2014, the judge agreed with Covington’s attorneys and issued a preliminary injunction to stop the second RFP from going forward.

The judge said from the bench that the state’s cancellation of the first RFP, “just defies reason … and it does suggest a manufactured reason to cancel, a trumped up reason, whatever you want to call it.”

The judge also called out the state for giving copies of Covington’s winning bid to the losing bidders, allowing the existing centers to potentially incorporate his already state-endorsed ideas into their proposal.

Bicha, in an interview with CPR News, disputed that there was any outside pressure, from the existing centers or the governor’s office to overturn the bid results.

“No, there wasn't pressure to do it from outside. The pressure was internally and mine,” said Bicha. “I had concerns about their approaches and methodologies. And so I asked DPA, ‘would you independently review the work that my team had done, because I didn't have confidence in what I was seeing.’ So that was the nature of the request of DPA. There was no political pressure.”

Whatever the motivation, crisis mental health services were now on hold after the preliminary injunction. The state and the existing centers appealed all the way to the state supreme court, but the appeals were all denied.

The state and the centers entered into mediation with Covington and his company Crisis Access to seek a settlement.

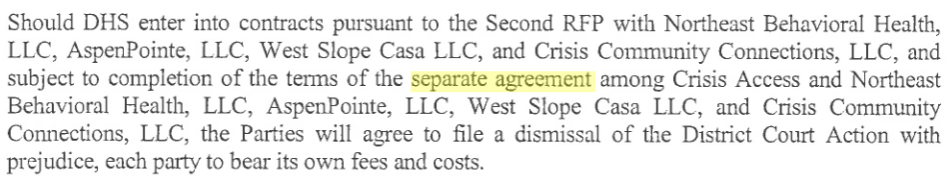

Eventually, he agreed to drop his lawsuit as long as a “separate agreement” was reached between the existing centers and his company, Crisis Access. The separate agreement is not a state record, and not subject to open records laws. It’s unknown how much, or even if, the centers paid Crisis Access to drop the claim against the state.

Also unknown: Where any funds that might have been paid to Crisis Access would have originated. The centers and CBHC refused to say, citing the non-disclosure agreement. The publicly available tax returns for the non-profit centers involved, which derive their revenue from a mix of state, federal and private funds, reflect no payments to settle claims. The centers refused to disclose the terms to CPR News.

What is known is that, though his department was a defendant in the case, Bicha was not in the meeting outside of court when the deal was reached between the centers and Crisis Access. The case just went away.

“From our perspective what happened was the two of them reached some sort of agreement,” said Bicha. “We never were notified of what the terms were. All we know is that the lawsuit’s going away.”

Asked if he had questions about the nature of the settlement, Bicha said, “Absolutely, but we had no right to find out what the settlement was,” since it was settled between two private parties in mediation.

But even while arguing that he wanted the system to change and that he had little choice in the decisions surrounding the crisis care contract in 2014, Bicha also still questions the entire structure of behavioral health delivery in the state, as the legislature tries to begin a realignment.

“These nonprofit corporations have guaranteed no-compete contracts with the state,” said Bicha. “But they don't have accompanying transparency into their financials, into lawsuit settlements, to board appointments, into all of those other factors that the public ought to be able to see and know about if they're going to get nearly exclusively state and federal dollars in no compete contracts.”

David Covington said he could not comment. He now runs a widely respected crisis mental health services company called RI International, based in Arizona. The company has direct care services in nine states, but not Colorado. Covington and RI’s approach is routinely cited in best practice guidelines by federal agencies and national behavioral health associations.

Experts in the field said the decision to reverse the award to Crisis Access meant Colorado missed out an opportunity to become a national model for crisis mental health care management.

David Covington and RI International have, “really been at the forefront of what a crisis system should look like,” said Dr. Amy Watson, a professor in the Social Work Department at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Watson was surprised to hear that Covington was essentially kicked out of Colorado. “He really has pushed things forward” in behavioral health innovation.

With Covington out of the picture, the state awarded the contracts and additional funding for crisis services to the existing centers.

The centers ran services until they found themselves battling the state again.

In 2018, Human Services again put the crisis services out to bid. This time, the center’s trade group, CBHC, sued the state directly, claiming changes to the existing system were unneeded.

But by bringing the program back to court, it allowed for some unflattering testimony, making clear that the existing centers, especially Mind Springs, which managed the crisis services for the Western Slope, were not fulfilling key parts of the 2014 contract they had fought so hard to win.

The assistant Summit County manager Sarah Vaine testified that she saw a map once that indicated the county had mobile mental health crisis services, provided by MindSprings.

“It says we have this in our community,” testified Vaine, yet it was not actually available in the community.

The attorney for CBHC and Mind Springs asked how Vaine knew that.

“It's based on community experience of calling the crisis line and being told to go to the emergency center and then having the CEO, and the local director, say 'we won't go to people's homes because there could be a risk to our staff.' And I then said, 'well, you could call dispatch and ask for someone to go with you. And they said, that's not part of our policy.”

Staffers from the state’s Department of Human Services said that those problems were really widespread. Habgood said in an interview that for all the people who are well served by the community-based centers, there are still times when they fall short.

“They do great work. They really do. They do serve people really well. And I want to be very clear on that is, and it's not just cuz I had relationships with them,” Habgood said. “There are people who are being served. There are times where they…they don't always do good.”

A Denver District Court judge dismissed the 2018 lawsuit from the bench, ruling on the narrow grounds that the state is entitled to put programs out to bid if they see fit.

The centers never bid on the new program. A group of so-called Administrative Services Organizations, or ASOs, now manage the state’s crisis services. It was meant as a way for the state to diversify away from the community mental health centers a bit, but the centers still provide the majority of mental health services in the state by contracting with the ASOs.

Still, the lawsuit sent a message.

“I think it's an intimidation tactic, right?” said Nancy VanDeMark, the former head of CDHS’s Office of Behavioral Health. “If you make it so difficult,” the state will think twice about adding competition to the existing centers.

“And I think it's been to some degree successful.”