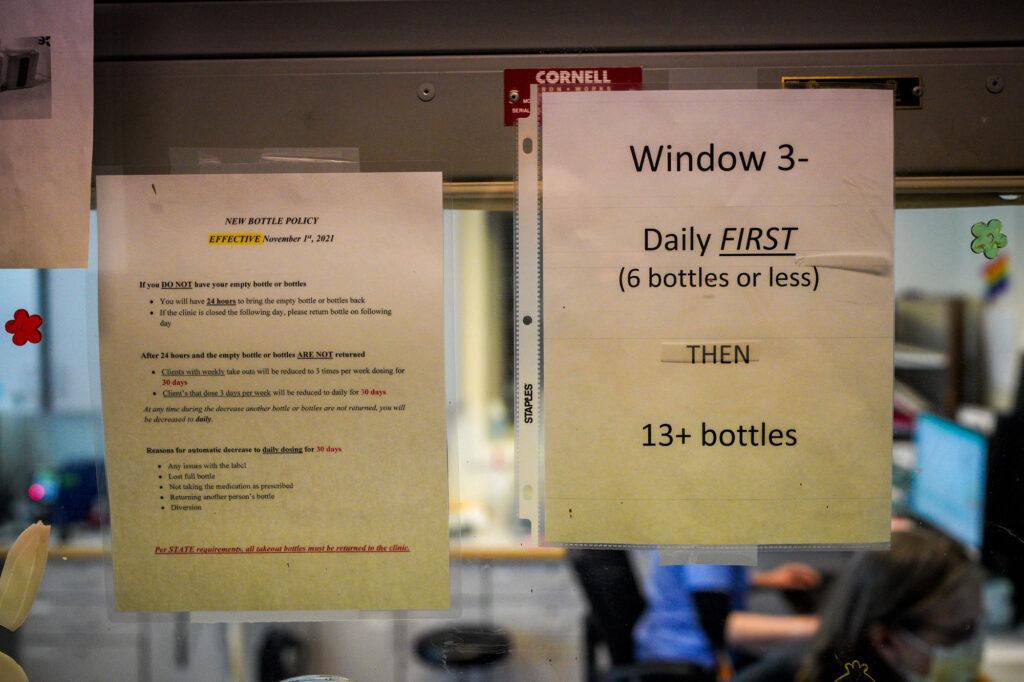

Every few minutes, someone new steps out of the elevator and takes a seat in the long, dimly lit hallway of Denver Health’s opiate treatment clinic. Some live on the streets. Others are dressed for the office. Each one is waiting to be seen by nurses behind glass windows.

“The front lines — this is it,” said nurse Erin Aufdemberge on one recent weekday morning. ”We are seeing people as they’re coming off the streets, and they’re withdrawing, and they’re trying to make that change.”

This second-floor medical office is one of the busiest opiate addiction treatment clinics in the Mountain West. The patients arrive as early as 5:45 a.m. — many on their way to work — to receive methadone and buprenorphine, medicines that can help manage addiction to narcotics like fentanyl.

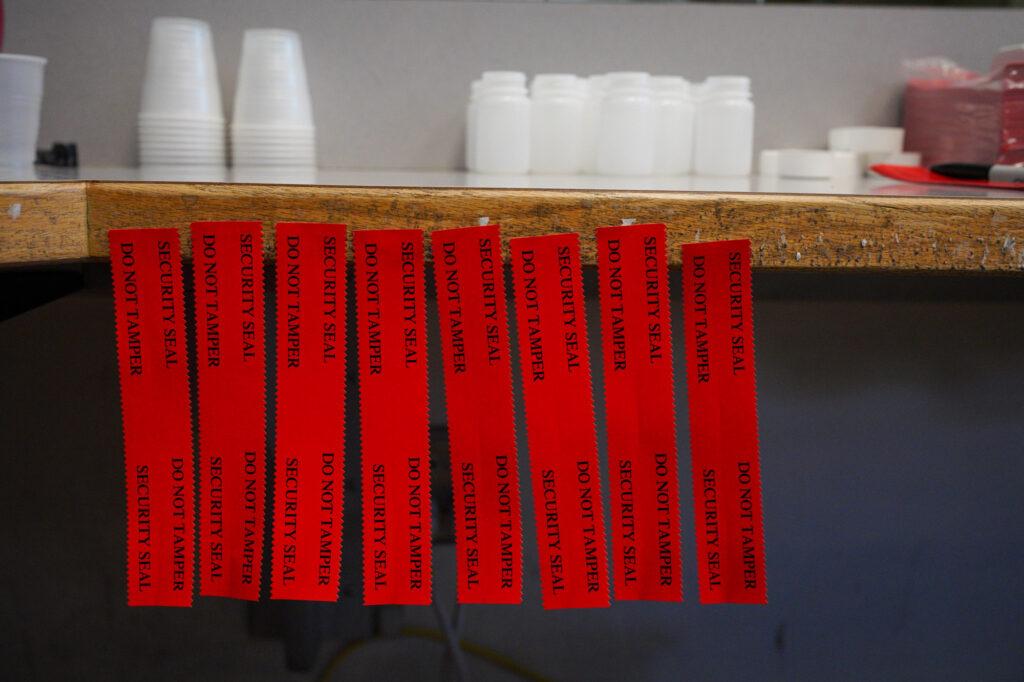

In the nurses’ station, a staffer measures cherry-red methadone into bottles, while another labels them for a patient. The patient stashes them in a lockbox alongside a dose of narcan, the overdose treatment drug.

Over the course of a single day, as many as 600 people may filter through this office, including perhaps a half-dozen new patients.

“It’s just nonstop, “ said Diana Warrilow, lead behavioral technician for the clinic. “I wear my running shoes — it’s constantly ‘Go, go, go.’”

It may soon get even busier. A proposed new state law could send hundreds more people into the state’s addiction treatment system, and clinicians are bracing for an unknown impact.

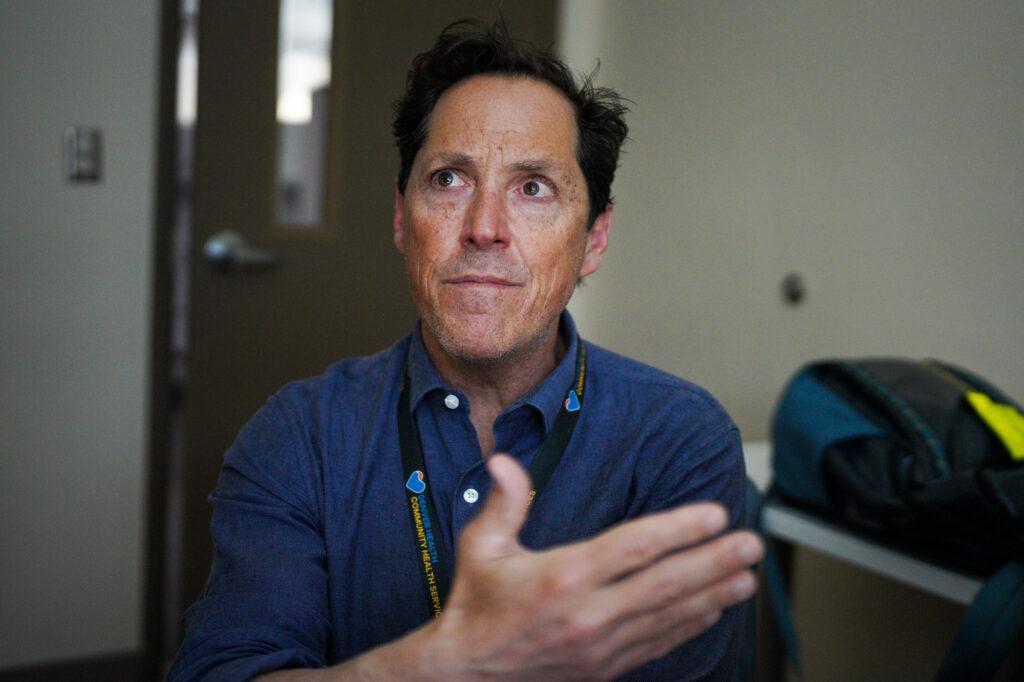

“We’re definitely going to have capacity issues. We’re going to have management issues and we’re going to kind of need to have all hands on deck,” said Dr. Josh Blum, director of the Denver Health clinic.

The state bill is focused on fentanyl, the deadly and addictive synthetic opioid. Among other changes, the legislation would require anyone convicted of fentanyl-related charges to be assessed and potentially ordered into treatment for addiction — whether that’s at an outpatient clinic like Denver Health’s or a more intensive residential facility.

No one seems to know exactly what to expect from that change, since there is no firm statewide data on fentanyl cases.

In a cost estimate for the bill, legislative staff projected that about 300 people a year could face fentanyl possession charges, which may result in treatment orders. They reached that figure by estimating that 5 percent of annual drug possession convictions involve fentanyl.

Some advocates think the reality will be higher. In Denver County alone, prosecutors filed about 340 fentanyl-related cases in 2021. In El Paso County’s 4th Judicial District, they’ve been filing about a case per day. (Not all charges lead to a conviction.)

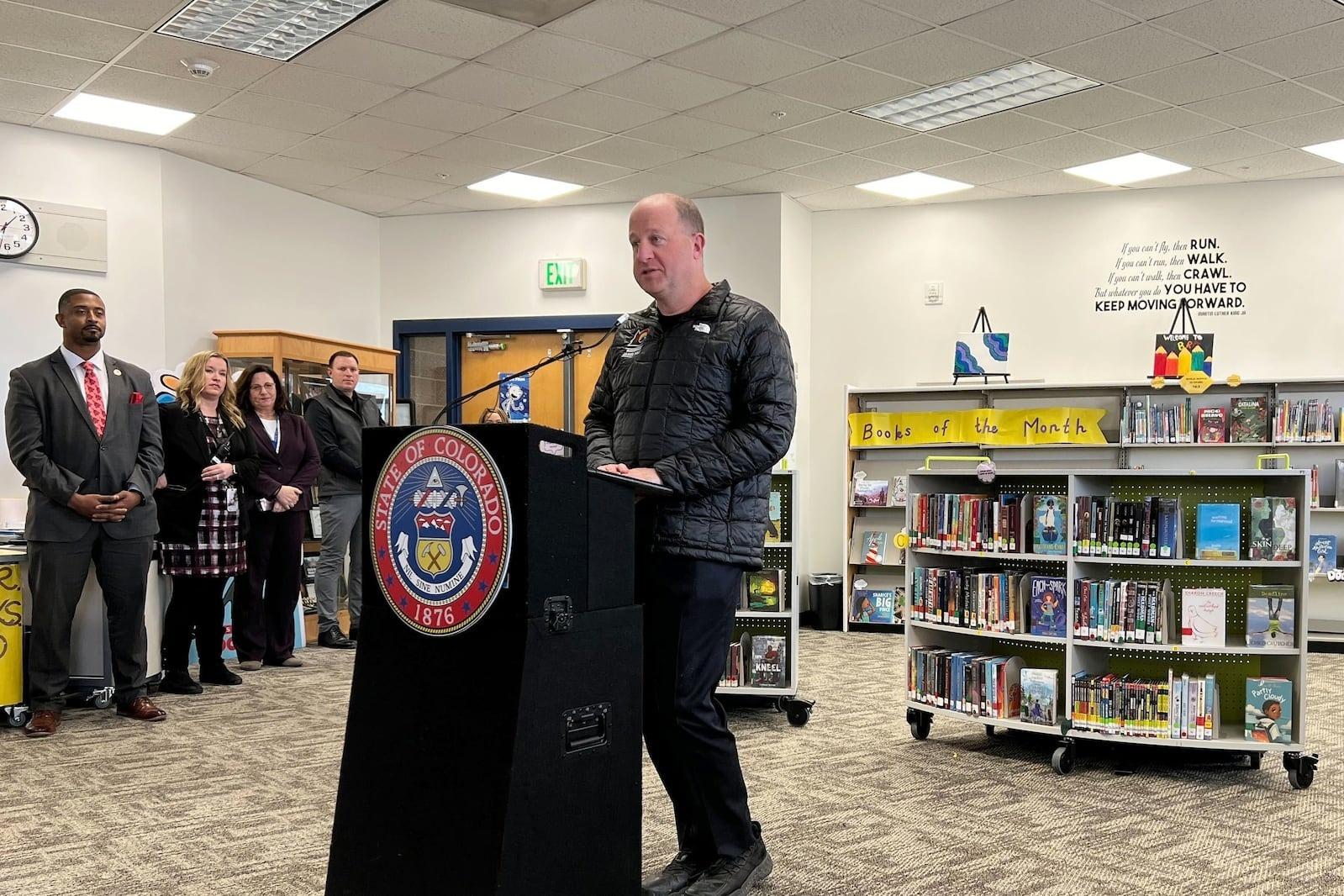

The goal of the new state bill is to “make sure that you’re receiving the evaluation and recommendations for additional treatment if needed — because fentanyl is more addictive than any substance that we’ve ever seen before,” said House Speaker Alec Garnett, a Democrat who is leading the bill, in an interview.

The question of pushing more people into treatment has divided clinicians, lawmakers and patients.

Some treatment providers, like Denver Health’s Dr. Blum, think an influx of new patients would ultimately be a good thing — even if it causes some temporary strains.

“I love the idea of more people being encouraged into treatment … because honestly people need this little nudge,” said Blum, who is confident his clinic can scale up to meet higher demand.

There’s some reason for optimism, especially at larger clinics. Today, about 19,000 people per month receive medication-assisted treatment in Colorado, and the state’s 30 methadone clinics are able to handle that demand without putting people on waitlists, according to state officials.

“I think it’s a good problem to have,” Blum said. “If there’s that many people seeking treatment, then it’s incumbent on us to meet people where they are.”

But those large methadone clinics only cover part of the state. The system is overloaded in other areas — especially for those seeking treatment in rural areas or residential facilities, where they may face long waits for care.

“We don't have enough providers at any level,” said Rob Valuck, executive director of the Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention.

“We don't have enough primary care doctors doing this. We don't have enough behavioral health professionals doing this. We don't have enough addiction treatment centers and providers doing this. We don't have enough school nurses doing this. We don't have enough.”

Months-long waitlists for residential treatment

In total, state officials estimate that more than 43,000 people in Colorado have opiate use disorder — and a separate data source estimates that far fewer than half of people with an addiction are currently able to get treatment in Colorado.

“The state doesn't have the ability to support what this bill is asking for, in my opinion,” said Butch Lewis, executive director of the Colorado Association of Recovery Residences.

Lewis is specifically concerned about residential services, where care is more costly and difficult to find, compared to outpatient services like methadone clinics. Facilities where patients can stay for days or weeks as they learn to manage their addictions are in short supply. Many have waitlists that are months long and include hundreds of people, advocates said.

The residential approach provides benefits that medication alone cannot, said Breeah Kinsella, executive director of the Colorado Providers Association, a trade association for substance-use treatment services.

Residential treatment “provides the connection. And for some people who have been living in addiction for a long time, they don’t know how to live anymore,” she said. “These recovery services … teach you how to live again, in recovery, without drugs, surrounded by a community of people who understand.”

The legislature isn’t doing enough to build out residential treatment capacity, she said.

“They’re mandating treatment and there’s no money for treatment,” Kinsella said. “We can hardly do what we’re being asked to do now.”

More broadly, shortages of all types of treatment are especially pronounced in rural areas. About a dozen Colorado counties are estimated to have zero or one clinicians providing addiction treatment, according to state data.

“It’s important to remember that there is a huge range in population (density) in our state,” said Steve Holloway, chief of the health access branch at the Colorado Department of Health and Environment. “On the other hand, we believe that people should not have to travel great distances for treatment.”

People ordered into treatment in some rural areas could face a drive of several hours to reach a clinician’s office, Kinsella warned.

State Sen. Brittany Pettersen, a longtime Democratic advocate on substance use issues whose mother has struggled with a long term opioid addiction, said she was frustrated that much of the legislative debate had focused on criminal penalties, not treatment.

“Right now, we have a waitlist that is around 450 people, currently, who want treatment, who are on the waitlist for residential care — and that's before this law goes into effect,” she said. “It’s just been really frustrating where this conversation is centered, because it is a very small piece of the larger issues at hand.”

What’s working so far?

State officials acknowledge that some areas of the treatment system are struggling to meet demand, but they also point to signs of progress.

For example, Colorado has closed part of its “treatment gap.” Nationwide, only about 20 percent of people who need treatment are able to get it. In Colorado, that number’s somewhat better at about 35 percent.

“We're gaining on the problem faster than other states, but we still have a long way to go,” Valuck said, citing federal data.

One reason for improvement is that the federal and state governments have expanded coverage for opiate treatment under Medicaid and related programs. The state also has instituted programs to improve access in rural areas.

For example, Colorado has in recent years enrolled about 1,600 physicians who can prescribe the drug buprenorphine for opiate addiction, a fourfold increase in just a few years, thanks in part to reduced federal training requirements and state efforts.

Using tele-health visits, these doctors are able to get the drug to patients in almost every county, said Marc Condojani, director of adult treatment and recovery for the Colorado Department of Human Services.

“Anywhere there’s a primary care physician, that’s going to create access (to treatment),” he said.

Advocates like Kinsella say that distributing buprenorphine via telemedicine is indeed an improvement, but they warn that medication alone can’t always help people. Additionally, buprenorphine may not be as effective as the more powerful methadone in fighting a fentanyl addiction in some cases.

“Transitioning from fentanyl specifically onto buprenorphine is really difficult,” Blum said. "Fentanyl is changing the game — we need evidence on novel ways to induct people onto buprenorphine. We need to loosen the restrictions on methadone."

Will federal money help?

Meanwhile, the state’s overall behavioral health network — an umbrella that includes addiction treatment — is set for a major boost this year. Lawmakers are planning to spend nearly half a billion dollars of one-time federal money to improve services.

But some treatment providers say they’re being left out. While some of the federal money will likely filter down to some addiction treatment services, none was originally earmarked for that purpose, Kinsella said. And the new money for treatment in the fentanyl bill is almost entirely directed toward jail-based programs.

This week, the House Appropriations committee amended one spending package to include $5 million for substance-use treatment beds for adolescents.

Part of the overall problem, providers said, is that the state doesn’t pay enough for Medicaid patients who are getting addiction services. Their reimbursement rates are about 20 percent lower than what other behavioral health services receive, Kinsella and Lewis said.

“There’s no reason we should still be living in this era where substance use disorder should not be treated the same as behavioral health,” Kinsella said. The difference in payments is rooted in the technical details of the types of professionals providing the services, according to state officials.

Kinsella contends that the gap could be closed with a few million dollars in state funds per year, which would attract matching funds from the federal government.

House Speaker Garnett said the topic of reimbursement rates “has come up a lot around this (fentanyl) bill,” and that he’s open to discussing them, but added: “I can’t do everything in this bill.”

The fentanyl bill also includes about $28 million for education campaigns, opiate antagonists, fentanyl testing strips and harm reduction grants, along with $3 million for medication-assisted treatment in jails.

Meanwhile, state analysts expect that it will result in felony possession charges for about 150 more people each year, contributing to an increase of nearly $14 million in spending on prisons over the next five years.

Will mandatory treatment work?

Beyond the dollars and cents, there are fundamental questions about whether the state’s new fentanyl bill will help people beat their addiction. The bill includes felony penalties for people who are "knowingly" in possession of more than a gram of the drug — or mixtures containing the drug.

Law-enforcement officers and others, including bereaved family members, said at a recent committee hearing that the threat of a felony conviction would keep people away from the lethal substance, and that the charges could be used as leverage to get people into treatment.

Others, including treatment providers and researchers, said a more punitive approach would disrupt people’s lives, and some cast doubt on the idea that mandatory treatment will really help them long term.

“There is a lot of uncertainty around whether mandated treatment is effective,” said Dr. Sarah Axelrath, who runs the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless opiate treatment clinic in Denver. “In most cases, anecdotally, treatment is most effective when people have decided they’re ready for their own reasons.”

Garnett said that he would introduce a plan to fund a study of the results of the bill.

“I am very sensitive to the fact that we have a system that’s under-resourced and doesn't have the capacity now —and that people may be stressed out about what could come,” he said. “We’re gonna track that — this conversation is not ending.”

At the Denver Health clinic, several patients said that conversation should include them.

“They don’t have any firsthand experience with addiction. There’s no voice for people that have actually struggled with substance abuse at the capitol,” said David Wasserman, 30, who is recovering from an addiction that began more than a decade ago with prescription opiates.

Three times a week, he travels more than an hour by bus to reach the clinic and get the medicine that helps control his addiction. He’s been clean for about five years, he said, because he was able to get treatment.

“It gives me stability. It takes care of my chronic pain. It gives me routine, it gives me a support system,” he said.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to reflect that the Denver District Attorney’s Office filed 340 fentanyl-related cases in 2021, each of which might include multiple charges, and to note the legislature’s recent move to fund adolescent substance-use treatment beds.