Since her first days in Congress, Republican Rep. Lauren Boebert has not shied away from controversy.

Her supporters cheer her media-grabbing moves — from the stylized video she released her first day in office touting her intention to carry her glock in D.C., to carrying a cardboard cutout of Vice President Kamala Harris around on a trip to the southern border.

But those same actions, most recently her heckling of President Joe Biden during the State of the Union, have many critics arguing she’s unsuitable for office.

Even as redistricting has made Boebert’s seat a safer Republican one, she faces a number of challengers, including one from her own party, all aimed at the tough task of making this incumbent a one-term congresswoman.

As the Republican primary heats up, it increasingly mirrors the wider divide that runs through the Republican party today, nationally and on the Western Slope, between those who like the bombastic style of Trump and the aggressive embrace of social issues, and those hoping for the return of a more Reaganesque party focused on fiscal issues, and less on divisive cultural ones.

Boebert pitches conservative credentials

When Boebert announced her reelection last December, she touted her record of standing up for freedom, her constituent work in the district and her conservative credentials. She argued she’s the type of Republican that voters need to send back to Washington D.C.

“We don’t just need to take the House back in 2022, but we need to take the House back with fearless conservatives, strong Republicans just like me,” she said at the time.

Boebert’s campaign did not make her available for an interview before the deadline for this story, but the Trump acolyte has made a name for herself nationally with her social media savvy and strong affiliation with the more radical wings of the party. According to the New York Times, her tweets around the January 6th insurrection even concerned some Republican leaders at the time.

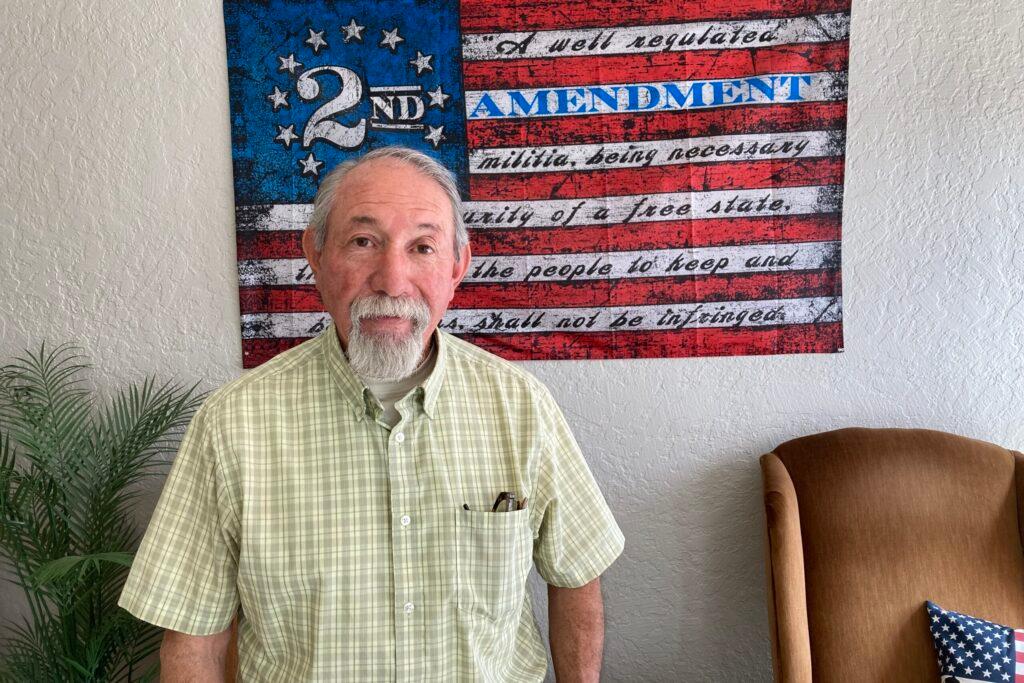

For many of her supporters, like unaffiliated voter Bob Clayton of Cortez, that’s just part of her being “a fighter.”

“I like everything about her. She’s tough. She’s for the people. And I agree with just about everything she’s ever done,” he said.

Boebert has strong support among the populist wing of the party. And her large social media following has helped fill her campaign coffers. She goes into the primary with more than $2 million cash on hand. She’s also gotten former President Trump’s endorsement for reelection.

Allen Maez, the chair of the Montezuma County GOP, is officially neutral about party primaries, but said voters there “want someone that will speak up, be seen.”

“We want to hear people say no,” he explained, sitting in Conservative Grounds, a coffee shop run by the local Republican women’s group where customers can pick up Trump and Boebert paraphernalia along with their lattes. “Lauren has said a few times, ‘Now I'm not going to vote yes on that. That's just bull crap.’"

But as much as they like her combative persona, the Boebert supporters CPR talked with struggled to point to any policy achievements in Congress. Her bills and resolutions, from forest management to impeaching Biden, have not gone anywhere in the Democratic-controlled House.

Still, some local party establishment leaders, like Mesa County Commissioner Scott McInnis — who himself held this seat in Congress for more than ten years — are bullish about Boebert’s future in office. “You know another couple of terms, I think she will be one of the most powerful congresspeople in the U.S. Congress.”

A challenger running from the center

But for all her popularity, Boebert’s polarizing behavior has also left many GOP voters wishing for something different. Outside a coffee shop in Delta, Republican Mark Schaffer dismissed Boebert as “a lunatic.”

“She doesn't seem like a traditional Republican at all. She just seems like a bomb thrower to me. So I don’t really have much good to say about her,” he said.

Instead, he’s planning to vote for her Republican primary challenger, state Sen. Don Coram.

Speaking from his hometown of Montrose, Coram said he has a pretty good life and was initially reluctant to jump into a bruising race for Congress, even though people have been encouraging him to do so for over a year.

“Finally it became so overwhelming, and the antics of our current representative — somebody had to do it and I felt that I had the best chance of doing it,” he said.

Coram has spent 11 years at the statehouse. He’s known as one of the Capitol’s more moderate Republicans, willing to work with Democrats on issues like improving civics education and expanding broadband infrastructure. In his run for Congress, he’s touted himself as an effective lawmaker who can work across the aisle.

“I think there's plenty of those that are frankly fed up with the rhetoric, the hate and division going on in Washington D.C.,” he said. “And they see someone who has actually been able to make accomplishments, do legislation, (and) bring programs back for their district.”

In contrast, Coram attacks Boebert as “all sizzle and no steak,” arguing she's taken credit for things that she actually voted against, such as touting provisions that benefit her district in a recent federal spending bill, despite opposing the overall measure.

‘Lots of mud being slung’

However, Coram’s long legislative record has also proved a fruitful avenue of attack for Boebert’s campaign.

It launched an attack website as soon as Coram announced his run earlier this year — a sign that she’s taking his primary challenge seriously.

Boebert’s campaign claims Coram unjustly enriched himself, by running legislation benefiting the hemp industry, while also owning a hemp growing operation. It cites a press conference he held to encourage the public to invest in his company, and an anonymous request for an ethics investigation into whether he improperly sponsored legislation to benefit himself.

Checks with the Colorado Attorney General’s office indicate no complaint was ever officially filed there. And if one was ever submitted to the state’s Independent Ethics Commission, it was dismissed too early in the process to be reported. The office only names names when a complaint is deemed non-frivolous.

Coram has come out swinging against these claims.

“Lies, lies, lies, and damn lies,” he said. “Frankly, I would wish that she would actually talk about policies, issues and solutions rather than have to lie her way through, to try to get the vote.”

However, her campaign is working hard to get these accusations in front of primary voters; CPR News saw one of these attack fliers on display in the Pueblo County GOP offices.

Rob Leverington, chair of the Pueblo County Republicans, said any campaign can drop off literature. “I'm sure there will be lots of mud being slung from side to side. You've already saw some out here with Congresswoman Boebert’s campaign literature. So, that's why we have elections.”

Boebert, herself, has come under ethics scrutiny during her time in the House. A Democratic lawmaker filed a complaint over over her actions leading up to January 6 that was eventually dismissed, and Muslim and Jewish groups also asked the ethics committee to look into comments she made about Rep. Ilhan Omar. She has also faced criticism for questionable mileage reimbursements.

GOP voters weigh their options

In Montezuma County, Allan and Carla Thayer are lifelong conservative Republicans. She homeschooled their children, their daughter open carries, they have a son in the military. Carla Thayer has reservations about both candidates.

“I do not like the way Coram goes across the aisle. He goes way too many times. But there are a few things I've seen in Bobert that have me concerned also,” she explained.

Sitting in their kitchen you get a sense of their principles. Carla didn’t vote for Biden and does not support his policies, but she still thinks people should be respectful of the office when he is speaking, and not go “screaming and hollering” — a reference to Boebert’s outburst during the State of the Union.

But more substantively, she wants to hear what each candidate is running for, not just how much they can trash one another.

Allan Thayer has voted for both Boebert and Coram in the past. As a member of the Republican Central Committee for the county he can’t support either candidate in the primary, but he summed it the challenge that Coram faces in this conservative corner of the district: “It's not that he's not popular. It's just, Lauren Boebert is more popular.”

To get on the ballot Coram collected signatures, allowing him to avoid the assembly process, which Boebert ended up essentially sweeping. The two campaigns are currently negotiating primary debates. He pitched four, she countered with two.

Making the Pitch, one unaffiliated voter at a time

When it comes to wooing voters, Coram is aiming for what he describes as the “80 percent in the middle”, those who are tired of extremes in both parties.

Primaries usually bring out a party’s most passionate base, but Coram is hoping to appeal to the largest bloc of voters in the district: those who are unaffiliated. Under state law, they’ll get both Democratic and Republican ballots, but are only allowed to return one.

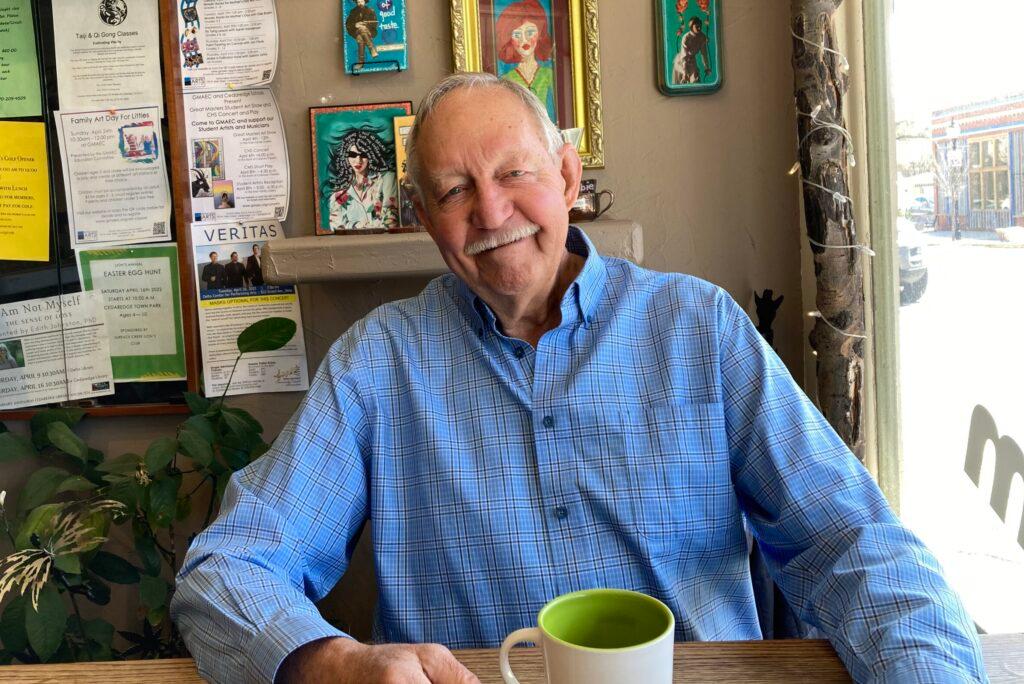

In Cedaredge, a small community located in a valley on the eastern end of Delta County, lifelong GOP voter Dennis Grunkemeyer said newcomers to the party have called him a RINO for his more traditionally Republican approach to issues. However, he considers them the ones who are Republicans In Name Only.

Grunkemeyer is no fan of Boebert and is glad that Coram got into the race.

“I started promoting him among my friends,” he said.

Those friends include David Starr, who walked into the coffee shop as Grunkemeyer was talking with CPR. Starr is a musician and business owner in Cedaredge. He’s politically unaffiliated and worried about what he calls real world issues — taxes, inflation, and paying for gas. He doesn’t see Boebert as part of the solution.

“I've got a lot of friends who are pretty far right of me politically. Not one of them can explain to me or point out to me one good thing that she's done for this district or for the state of Colorado,” he said. “They say, ‘Oh, she's funny. She's cool. She's cute.’ Well, that's just, that's just a clown show. That's all Vegas.”

Starr hasn’t decided yet whether he will vote in the primary. He said he generally likes to vote for positive reasons, not against someone. This is when Grunkmeyer chimed in.

Sure he conceded a vote for Coram could be viewed as just a vote against Boebert, but then he added, “I think we need somebody there that at least has the experience and the ability. He's known in the Colorado legislature as being a compromiser… being willing to talk to the Democrats over issues that are important to his district.”

Starr left the conversation saying he will look into Coram some more.

Some Democrats seek to have a say

In a district that has been represented by a Republican since 2010, and now tilts even more in the party’s favor after redistricting, some Democrats are also considering switching to unaffiliated.

Joe Padon, a teacher in the heavily Republican Mesa County, was a Democrat until a couple of months ago, when decided he was done feeling like he didn’t have much of a say in who the district’s representative would be. “I wanted to vote in whichever primary I could. And in this case, this year (it’s) the Republican primary.”

Padon said wants a congressperson who is “realistic.” He got the idea to switch affiliation from friends, but it wasn’t until he and his mother-in-law were talking about it that they both decided to make the change.

At a Democratic event in Montrose, a number of attendees said they knew people who switched, and a few had even gone through with it themselves.

It’s unclear how many Democrats have made the change. Voter data released by the state do not show dramatic changes in voter registration numbers in recent months.

For many Republicans, like Carla Thayer in Montezuma, the idea that Democrats would drop their affiliation to vote in her party’s primary doesn’t feel fair at all.

“I think it's crazy. You know? I mean, ‘cause they're just gonna put in who they want,” she said. “They can come in, vote who they want to and then ruin our side of it. So we're stuck with somebody that we don't even want.”

A group of Colorado Republicans sued earlier this year to try to lose party primaries to unaffiliated voters, but the case was tossed out. It’s an argument Boebert supports; she said in a statement, “Members of various political parties should choose their nominees in a closed primary system.”

Some local Democratic leaders are questioning the wisdom of the idea too, concerned it could drain voters from their own contested primaries up and down the ballot.

“People are gonna switch over to vote for one person — against Lauren Boebert,” said Scott Beilfuss, co-chair of the Mesa County Democratic Party. “But … the Democrats have some important races in their primaries.”

For all the now-former Democrats who fear the stakes are too high to stay in the party in a district that favors Republicans by 9 points, there are still current party members who argue the best way to beat Boebert or Coram is to elect the best Democratic candidate they can for the race.

Talking with Padon, even he has doubts that there are enough like-minded unaffiliated voters in CO-3 to make the change that he wants to see happen. “I don't know that it will be, but I can hope.”