Principal Jeff Rasp can count the number of Indigenous students at Strasburg High School on one hand, but that tally hasn’t stopped the school from building a deep relationship with the Northern Arapaho Tribe over the last seven years.

For the first time since the pandemic began, representatives from the tribe drove down from the Wind River Reservation to revisit their ancestral territory and meet students. Since 2015, the rural school of about 300 students has opened its doors to the tribe for a day of celebration and education. Rasp said the relationship grew out of concern over the offensive nature of their sports teams’ mascot and name, the Indians.

“We wanted to examine our mascot. Is what we're doing honorable?” Rasp said. “So we went straight to the source. We talked to the Northern Arapaho.”

Together with the Arapaho people, Strasburg redesigned their mascot to make it more “accurate and genuine,” while continuing to be known as the Indians. And every year, to make sure students know the significant history of Indigenous people in Colorado, the school holds an Arapaho Day gathering with tribal representatives.

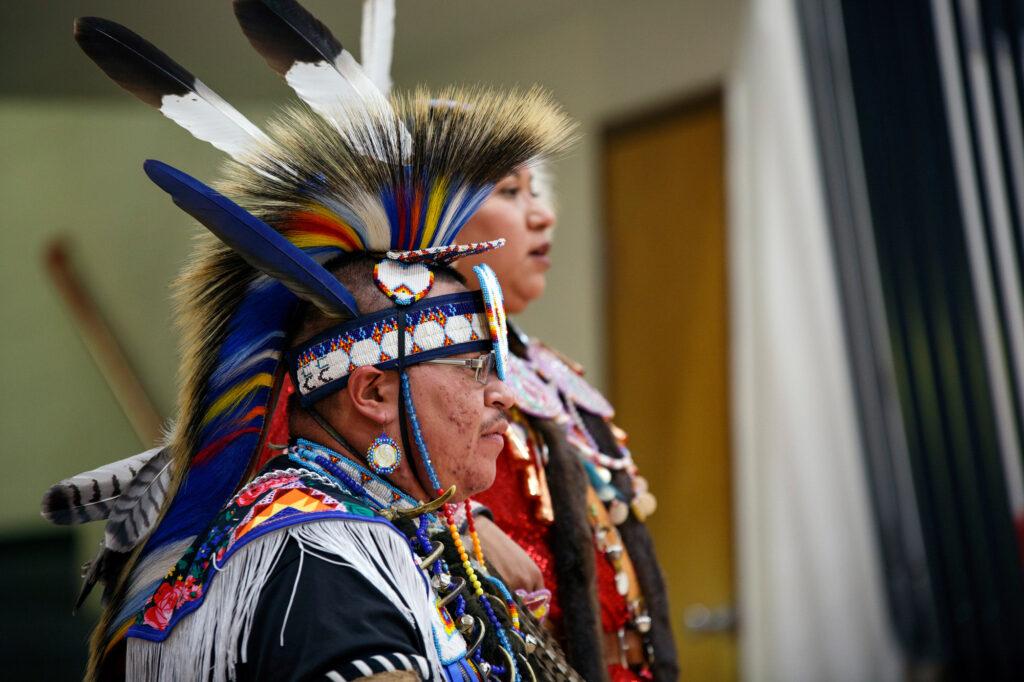

This year, students participated in a pow-wow after being blessed by tribal elders. A drum circle played songs in the gymnasium as the tribe performed a variety of traditional dances.

“I grass dance,” said Wyatt Sunrhodes, a 17-year-old Arapaho. “[It] sounds peaceful, really, the movements of it. [The movements are] like the blades of grass moving along with the wind. It's calming really.”

For upperclassmen, the ceremony felt similar to the ones held before the pandemic, except for the finale, when students were invited to the gym floor for a lesson. Together, they learned how to tell a story by dancing with flexible hoops that the Northern Arapaho use to represent animals and designs recurrent in Indigenous stories.

“I just watched, and I tried to do what [the performers] did. Obviously, it was not nearly as good as she was, but I had a lot of fun,” said Cole Nickell, a senior who joined the dance.

Stephen Seminole, an Arapaho member and Navy veteran, said including the students — most of whom do not come from an Indigenous background — is an important part of educating others about different cultures.

“That's probably the first time that we actually had 'em on the floor to do something like that,” Seminole said.”Rather than just looking, how about let's be part of it too, you know? So then you walk away with something that’s [like,] ‘Hey man, I did that.’”

At the end, the Arapaho visitors gifted Rasp with a blanket and honored him with a dance — a token of gratitude for his friendship over the years. After nearly two decades, Rasp is stepping down from his position as principal and returning to his roots as a counselor.

But for Seminole, the ritual was a subtle reminder of the isolation and grief many tribes experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“That's what we do for a lot of our elders,” Seminole said. “We haven't had the chance to actually honor them like that because a lot of 'em, they passed away. But we still do that dance for them ‘cause they’re going to a better place.”

The Northern Arapaho Tribe has lived on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming since 1878. Before that, they lived on the plains of Colorado. The tribe was one of the two targeted by the U.S. Army in the Sand Creek Massacre, one the nation’s most notorious attacks on Indigenous people. Today, the tribe has about 10,000 enrolled members.