Claire Kimbel clearly remembers November 29th of last year. It was the day a new resident named Allison arrived at the sobriety home where Kimbel works in Lakewood.

“She was kind of a firecracker,” Kimbel said, laughing at the memory. It took an unusually long time to complete Allison’s intake — because she kept stopping to make friends with the other women at the house on 6th Avenue.

By the time she got to Monarch Sober Living Homes, Allison, a mother in her 30s, had suffered for years from mental illness and addiction. CPR News is withholding her last name to maintain her family’s privacy, at their request. She used opiates, including fentanyl-laced pills. But on the Monday she arrived at the residence, she was newly sober after several days in detox — and she was hopeful.

“I could see that she really felt like she was starting over, starting something new,” Kimbel recalled.

The months ahead would bring progress and healing — but also struggles and relapse. In March, Allison died following an overdose.

Her death came just as Colorado lawmakers began debating a new approach to the felony drug. Now, the state is poised to increase the criminal penalty for possessing small amounts of fentanyl to a felony. The change was one of the most debated ideas at the legislature this year — with experts, advocates, and lawmakers all deeply divided over whether that approach will help, or harm, people like Allison.

Those who loved her, and who tried to save her, are left with different answers.

A “beautiful life” felt within reach

The Monarch residence in Lakewood is easy to miss —a suburban, stone-fronted McMansion, though an unusually large one. Inside, it’s stuffed with cozy touches, like the “Home Sweet Home” sign and a basement movie room. At any moment, it’s occupied by a dozen women in recovery and two staffers.

In those early weeks, Allison worked hard at the program — constantly attending meetings and making connections. She made it to a month sober, and then two. She got a car and worked jobs at a senior home and as a waitress.

“I thought if she could hold onto what was driving her in those first 30 days, that she could do some really great things: stay clean and sober, and help a lot of people,” Kimbel said.

Allison was fortunate to have access to residential services, which often have long waitlists and simply don’t exist in many rural areas. Treatment and recovery facilities, almost everyone agrees, should be the first line of defense for addiction.

But recovery is a fragile thing. Cali Peterson is co-owner of Monarch Sober Living — and, as a recovering opiate addict herself, she started to notice changes in Allison after a few months.

“I could definitely see it coming, and it's so frustrating in those moments,” she said.

The relapse seemed to be triggered by the onset of an unrelated medical condition late in January. Allison had an episode of Bell’s palsy, a sudden onset of facial paralysis that can temporarily alter someone’s appearance, similar to a stroke.

For someone with addiction, Peterson said, that kind of change can be destabilizing: “We are already self-conscious about everything and overthinking everything, and all these emotions are so overwhelming.”

Allison was taking a medication called Suboxone, which reduces cravings and can even cancel out some of the effects of other opiates. But Peterson and Kimbel suspect that when Allison started using again, the fentanyl she took was powerful enough to overwhelm the medication.

The young woman was in a critically dangerous phase, since people who relapse after a period of sobriety don’t have the same tolerance as they did before. And fentanyl pills can be especially deadly because the dosage is unpredictable and the drug is lethal in small amounts.

Allison started trying to avoid drug tests, then suffered an overdose in a Costco bathroom — and she was soon asked to leave the house so her use didn’t endanger the other women’s sobriety.

“You just wanna shake 'em,” Peterson said. “You have this beautiful life waiting for you, and like you can't see it it's there, you know? But you're so stuck in this.”

Peterson worked with Allison’s mom to get her back to detox, but Allison apparently decided not to go. She returned to the residence, uninvited, at the end of January. Staff wouldn’t let her inside — but a short while later, they realized her car was still in the driveway. She was in the vehicle, overdosing.

“She was unconscious. She was gray. She was not breathing very well,” Kimbel recalled.

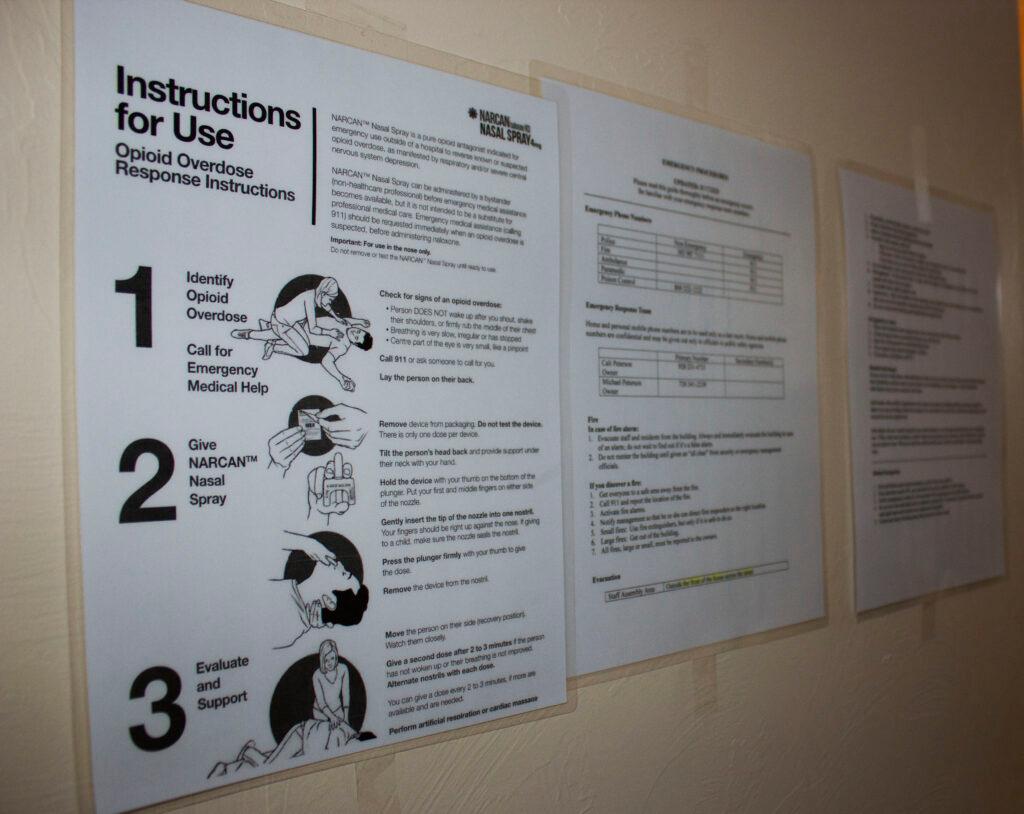

The staff grabbed doses of Narcan from the house and, within minutes, had revived Allison.

Is jail ever the answer?

Peterson wasn’t on the scene — but she was on the phone, urging others to get the police involved.

“Tell them she needs to be arrested,’” she recalled saying. “Because at this point, this was three overdoses in a week. She wasn't willing to go to detox. In my mind I thought the best solution for her to have a shot was to go sit in jail for a while and sober up.”

This moment exemplifies the debate that lawmakers and others have had about this issue: Are police and prosecutors ever the best option to help people whose crime is essentially addiction?

Peterson thought that jail was Allison’s best chance to survive, and to have a chance of getting back on the path to recovery. In fact, years earlier, Peterson herself had gotten sober on a jailhouse floor in another state.

“Maybe that would scare her enough and wake her up enough,” she said.

The proposed state bill would allow police and prosecutors to treat fentanyl possession cases, potentially including Allison’s, more harshly.

Under current Colorado law, anyone caught with less than 4 grams, or about 40 pills, can only be charged with a misdemeanor, unless they are suspected of drug dealing.

But the nearly completed bill would lower the limits, allowing felony charges for anything more than a gram of any substance containing fentanyl. It doesn’t go as far as many Republicans and a few Democrats wanted; they pushed for “zero tolerance” felonies for all possession of fentanyl.

Supporters of tougher penalties, including Peterson, argue that it’s not about punishing people with addictions, but that an arrest and the threat of a felony charge are sometimes necessary to get people like Allison to get treatment. Under the bill, some people could lessen their criminal penalties if they complete treatment.

On the day of the overdose, Allison had a few pills on her and some syringes with an unknown substance, according to Kimbel; the exact amounts are unclear. Police offered her an option: She could go to jail, or she could go to a hospital.

“She chose to go to the hospital, so they wouldn't arrest her,” Peterson said.

A police report confirms that Allison was taken to a hospital, but officers wrote they were not sure whom the fentanyl belonged to. It does not describe the hospital-or-jail offer.

Allison’s final days

Allison continued to seek treatment after she was hospitalized, but her willingness to participate came in fits and starts — as can often happen for people in the grips of an addiction crisis.

A few days after the overdose in the driveway, she called Peterson and told her about grandiose plans to leave Colorado and start a new life. The escapist talk set off more alarm bells.

“And this is when I remember calling her mom and saying, like, ‘She's gonna die,’” Peterson said.

Peterson and Allison’s mom kept looking for anywhere that could keep her in treatment. They found a slot in a 30-day inpatient program, Peterson said — a near miracle considering Colorado’s shortage of residential treatment beds. She was still resistant.

“When you see the willingness go away, it's just addiction has hold over over them,” Peterson said.

Allison’s mom is an elected judge in another state — and next, she went to the courts in Colorado. She had her daughter involuntarily committed through a court order to substance abuse treatment. It seemed like the only way to get her back to her senses.

But even that wasn’t enough. Once again, Allison left treatment and returned to the Monarch residence.

“She just went in for a hug and collapsed crying, and just feeling devastated and asking for help,” Kimbel said.

The staff called 911, hoping someone would enforce the court order and take Allison back to treatment. Kimbel recalled telling a dispatcher that Allison would die if she left the home. But, according to Kimbel, the dispatchers said they didn’t have access to the court documents and couldn’t act on them.

Eventually, Allison left the home.

Days later, she suffered the overdose that would kill her.

What would the new legislation change?

Allison was one of hundreds of people who will die from fentanyl overdoses in Colorado this year. In recent weeks, lawmakers have heard from many of those left behind — the grieving friends, siblings and parents.

Several parents have testified to lawmakers that they “would rather have a felon than a dead child,” saying they believe the fear of criminal consequences could have helped their beloved. Law-enforcement leaders said that having the option of assigning felonies would allow them to target lower-level drug dealers and also give users a greater push to treatment.

Peterson agrees: After being arrested for heroin possession, she too faced multiple felony charges in Arizona and Ohio. But she got sober, resulting in the charges being dismissed in one state and reduced to a single misdemeanor in another.

“I had two options,” Peterson said — prison or a new life.

Colorado’s new bill will offer people a similar option to reduce a felony possession conviction to a misdemeanor. But others have said that a harsh criminal response would only have ostracized their loved ones.

“If my son was told that, if he was felonized, he would have been broken. And (we) would have been robbed of two years of love to and from him in our lives,” said James O’Connor, a public defender who lost his son Seamus, at a committee hearing.

Felonies can carry lifelong consequences. Even when they don’t result in imprisonment or convictions, they can harm people’s careers, separate families and drive addicts deeper into despair. Peterson acknowledges that her own criminal charges derailed her hopes of working as a nurse. She also benefited from her family hiring a lawyer.

“It completely changes the trajectory of your life. You always have that hanging over your head, you know. It doesn't ever go away,” Peterson said.

Allison’s mother takes a different perspective. She isn’t closely familiar with the Colorado bill — but she warned that simply turning to felonies overlooks the real causes of addiction. She doubts that any criminal court could have saved her daughter.

“She has mental health issues which predated her drug use. It’s much more complex than just someone who has a drug problem,” she said. “People who have drug problems have some underlying issue.”

The fear of jail “wouldn’t have deterred her, and that wouldn’t have motivated her,” the grieving mother added.

She wants time and effort to instead be spent on treatment.

Colorado’s bill dedicates $10 million for treatment and around $15 million more for harm reduction measures, such as testing strips and narcan.

It also is expected to increase prison spending by up to $7 million as more people are incarcerated over the next five years . However, that money would only be spent for people imprisoned for distribution. The new possession felony is written so it would only lead to jail, not prison.

What do researchers say about tougher penalties?

The threat of harsher criminal penalties does little or nothing to change drug use and other behavior, said criminologist Daniel Nagin — reflecting a view widely held by researchers and reformers.

“The harsher penalties for possession of fentanyl — there is no evidence that that is going to be an effective way of reducing the use of fentanyl-related drugs,” said Nagin, a professor of public policy and statistics at Carnegie Mellon University.

For example, there is no evidence that drug use is lower in states with more severe punishments, according to a study by Pew Charitable Trusts.

There is more debate around the idea of whether it can be effective for the authorities to use the threat of felonies and other methods to force people into treatment once they’ve been arrested. Nagin said some people may be more willing to attend treatment to reduce a felony charge, as the bill proposes.

But, “the only way this policy innovation can possibly be effective at reducing drug use is if the treatment option that's offered — to get a reduction to a misdemeanor — if that treatment is available and effective,” he said.

The availability of treatment differs vastly throughout Colorado. The treatment drug methadone is often available in cities, but it’s rare in rural areas — where patients might only have access to buprenorphine, a medication that can be less effective for some fentanyl users. There also is a dire shortage of residential treatment beds statewide.

The use of criminal charges can be an effective motivator for some, agreed Jonathan Caulkins, also a professor at Carnegie Mellon.

Over time, some research has shown that “it works to coerce people into treatment,” he said. “The longer you stay in treatment, the better you do. And if dropping out of treatment means there’s gonna be a criminal sanction, that can be a motivation.”

But there also is rising criticism among some advocates and academics about the idea that people should be coerced into receiving medical care, Caulkins said.

The bill also creates other possible inequities, said Rep. Mike Weissman, a Democrat who opposes the new felony penalties. Some judges could set tougher rules around what counts as “completing treatment” to have a felony reduced. And the authorities in some jurisdictions will use the felony charges more aggressively than others, he noted.

Caulkins, of Carnegie Mellon, said that there are few “great answers” to healing addiction. In concept, he said some parts of the Colorado bill could dissuade drug use. But he said that much of what happens next hangs on how police, prosecutors and judges wield their new power.

“It all depends on the amount that you trust the police and prosecutors to use their discretion well,” he said. “In 2022, we’re in a time when public trust of the police and the prosecutors is very low.”

The consequences may not be obvious for years, said Bryce Pardo, associate director of the Drug Policy Research Center at the RAND Corporation.

The “war” on drugs that began in the 1970s led to an explosion of incarcerations for drug charge — from 25,000 held in prison in 1980 to nearly 300,000 in recent years. That has “created a huge headache that a generation later (society) had to deal with, disrupting families and communities,” Pardo said.

In today’s policy debates, “those other kinds of considerations are very distant. It’s very, very hard to have that conversation.”

In mourning

The last time Cali Peterson saw Allison was in a hospital, where she was on life support after her final overdose.

Peterson took her hand — the hand of a mother, of a friend, of someone whose struggles were so similar to her own — and said goodbye.

“She really fought hard, and I know she loved her daughter, and I know she loved her mom,” Peterson said. “She was just like a beautiful person, but she just couldn't, she just couldn't do it anymore. You know? So I just told her it was OK to go.”

Later, she watched Allison’s memorial service over a video stream. It was the first of three funerals she’s attended this year — all lost to fentanyl.