Denver’s air was dirty. Vehicles were a leading contributor. And Colorado’s politicians thought they had a solution: incentivize drivers to ditch their cars with free rides on public transit in metro Denver.

"A lot of people are talking about air pollution these days. It's nice to be able to announce that the Regional Transportation District and those of us in the State Capitol are actually able to do something about it."

That quote, from then-Gov. Dick Lamm, is from March 1978. But it echoes today. State leaders are once again poised to make transit fares temporarily free. A Democrat-sponsored bill nearing final passage would provide $28 million to help make transit free during the state’s smoggy summer months over the next two years.

“This is a bill to help clear our air,” state Sen. Faith Winter, D-Westminster, said before a Senate floor vote in April.

An RTD spokeswoman said the agency is planning to waive fares during August 2022.

But opponents do not believe that temporary free fares will shift enough drivers onto transit to improve air quality. And a federally commissioned report on RTD’s 1978-79 experiment, as well as more current research from around the world, supports that skepticism.

Ridership boosted, but not by enough

In January 1978, a banking executive told attendees of a seminar on growth that free transit would help cut the “heavy brown funk” that hung over Denver.

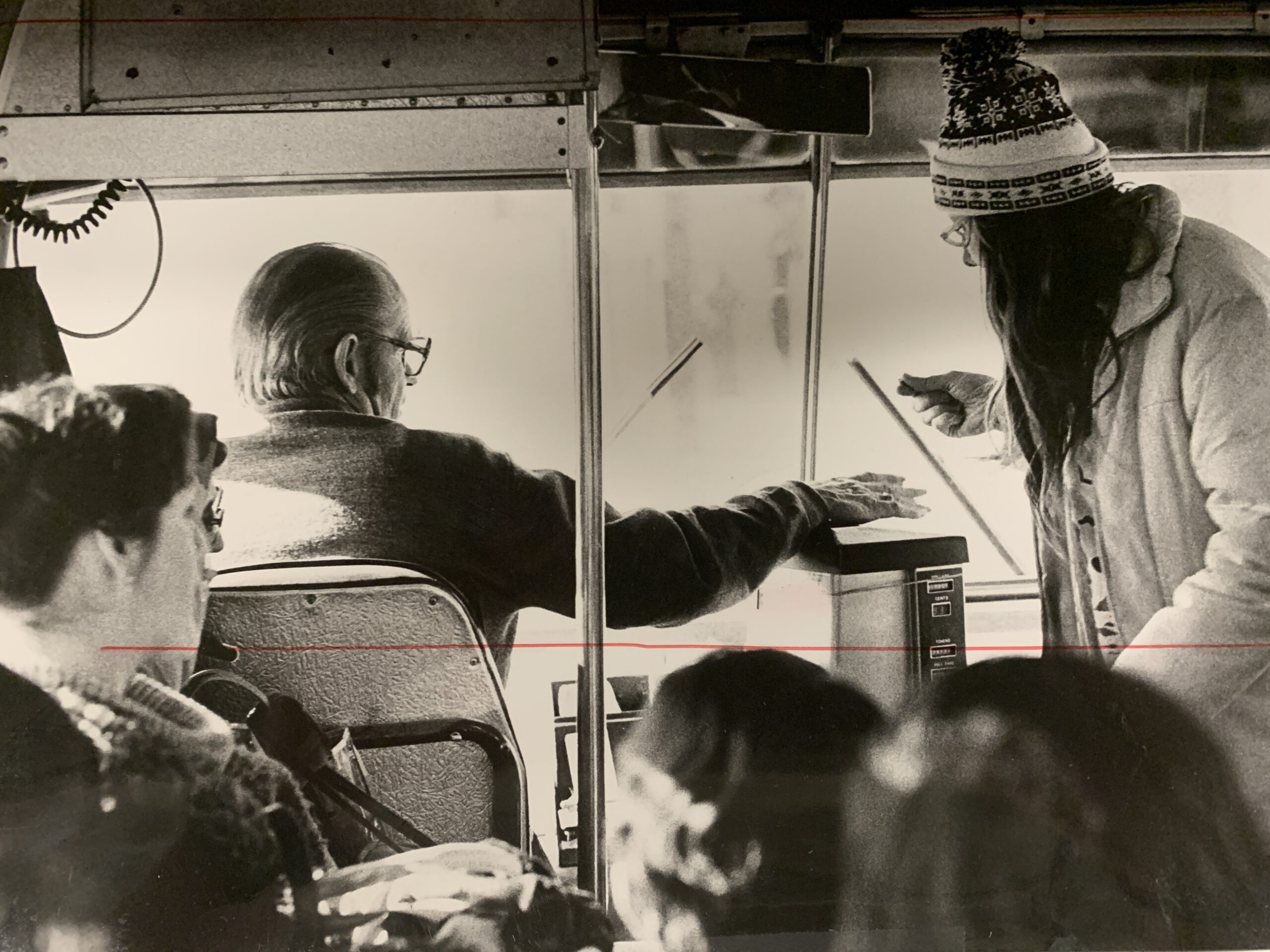

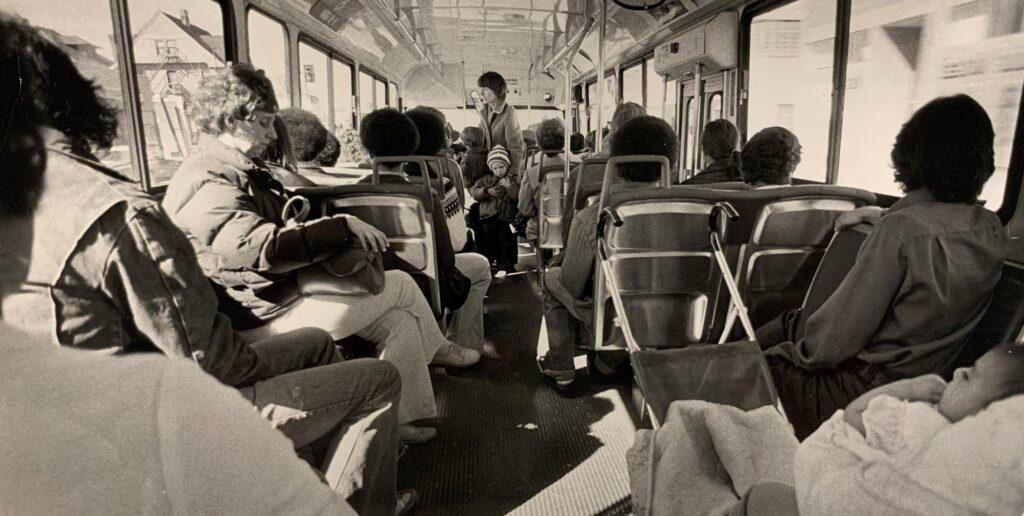

RTD eliminated fares, with the exception of during morning and afternoon rush hours, just a few weeks later. Early press reports were positive, quoting commuters who were happy to save gas money.

The federal report on the experiment’s outcomes showed that the free fares resulted in a significant ridership increase over the 12-month-long program. But it also found that only about 12,000 bus trips a day were made by former drivers or auto passengers, amounting to a decrease in driving so small it was indistinguishable from typical daily variations in driving patterns caused by things like weather.

"In general, a free fare transit program by itself appears not to be a very effective strategy to improve urban area environmental quality,” the report concluded.

Transit accounted for less than 3 percent of all area travel in the late 1970s, the report noted, so even a doubling of ridership could only be expected to reduce auto travel and pollution by a small amount.

Federal, state and local governments had boosted car travel for decades by this point by subsidizing sprawling suburbs, large parking lots and massive highways that made car travel all but necessary for most. Denver’s “brown cloud” only improved after the federal government raised vehicles’ pollution standards.

The new bill won’t be a 'panacea' for air quality, but it will have other benefits.

Cars are much cleaner than they were in the 1970s, but their emissions are still an environmental and health problem. Vehicles are a leading contributor to summertime ozone concentrations that have reached record levels in recent years and have led the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to declare the Front Range a “severe” air quality violator.

“I don't think we're in a place to claim that this will be a panacea,” said bill sponsor, state Rep. Jennifer Bacon, D-Denver. “But ... we've got to try as many things as we can because what's happening here [with ozone] is just so hazardous to our health.”

Bacon said that free fares will have other benefits like increasing access to opportunities for Coloradans without a personal vehicle.

One survey of low-income riders found that they’d rather have buses and trains run more frequently and to more places over cheaper fares. But it’s not clear where RTD could get the revenue to boost service significantly. A 2021 state law that will raise billions of dollars for transportation does not have any dedicated new funding for RTD.

The free-fare experiment made the job harder for drivers. RTD doesn’t want to repeat that this time.

“Free Bus Rides Plus Kids: Chaos,” read one June 1978 Denver Post story that detailed “rowdiness and horseplay,” and more serious problems. Vandalism, drunkenness and assaults on passengers and drivers all increased substantially because of the free fares, according to the federal report.

Sally Frederick, who started driving RTD buses in 1978, said one passenger threatened to break her arm when she told him he needed to pay the fare during rush hour.

“I think everybody thought it was a big mistake,” Frederick said of the free fares. “At least the drivers did.”

Safety and security are top concerns for union leaders and RTD brass, whose struggles to hire and retain more drivers and attract passengers are limiting the service they can offer. Drug use and other “unwanted activities” at Union Station and across the RTD system are seen as big impediments toward those goals.

“I do believe in the program,” RTD General Manager and CEO Debra Johnson said of the free-fare bill during an April RTD board meeting. “But also I have an obligation to ensure that our employees have a safe working environment.”

It’s not clear whether state money could be used for security expenses. And even if it’s allowed, RTD spokeswoman Pauline Haberman said, the agency is still having trouble hiring security staff.

RTD’s vehicles became “mobile shelters” early in the pandemic when the agency temporarily suspended fare collection, said Amalgamated Transit Union Local 1001 President Lance Longenbohn. That dynamic has persisted on some routes, he said.

“If [commuters] go down and look at a bus full of people smoking fentanyl, which unfortunately is happening … they’re not going to come back,” he said.