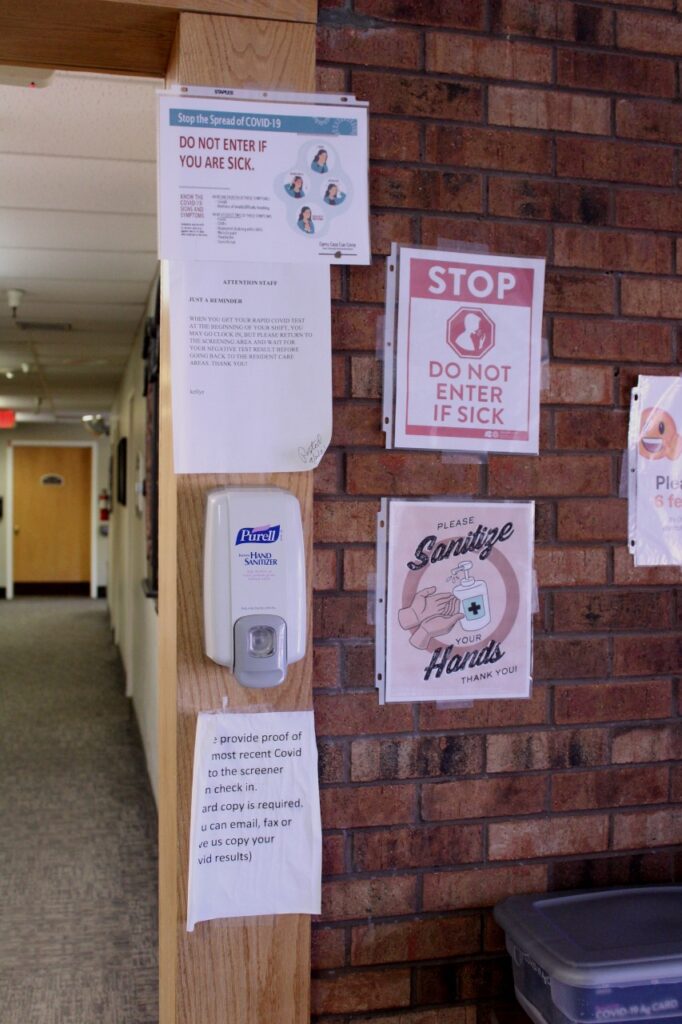

The lobby of the Cripple Creek Care Center is filled with reminders that the COVID-19 pandemic is still happening. Paper signs taped to the wall read "please sanitize your hands" and "masks required beyond this point." Everyone who comes in is required to check their temperature.

But it's quiet, a scene of what's to come.

After 47 years in operation, the Cripple Creek Care Center is closing in June. It's one of the nearly 400 nursing homes throughout the U.S. that could shut their doors this year, the direct result of staffing shortages.

Lawrence Cowan is an administrator at the care center, located in rural Teller County. He's also been working the night shift as a nurse to make up for low numbers.

"In 35 years, I've not ever been through this, and I don't ever want to again," he said.

The extra hours aren't the hard part, though. For Cowan, letting his dedicated staff go and saying goodbye to residents has been heart wrenching.

"They're our family," he said. "And it's going to have an impact on them because statistics show that a year from now upwards of possibly half of our people won't even be living anymore because of the transfer trauma that happens when moving from one location to another."

Before the center closes, it's Stephanie Henrich's job to find new homes for the people who live there. She is the social service director at the Cripple Creek Care Center (CCCC).

Henrich said it's a difficult task, as there is only one other skilled nursing facility in the entire county. Finding nursing homes that accept Medicaid or VA benefits is also hard, Henrich said.

"Some of these residents have been here 25 years or more. This is all they know and now they have to go somewhere else and start all over with people they don't know. So we're sending letters with them stating their likes, their dislikes, so maybe the facility they go to can deal with them better and they can acclimate faster," she said.

Henrich drives nearly four hours each way to work every week, traveling from San Luis.

"I come up here and stay the week, help them out and I can't desert them now," she said. "I've been with them for six years. I can't just walk out, so I have to see it to the end."

"[There's been] lots of tears shed by family and residents," she said. "Some residents feel like we're kicking them out. We feel like we're being kicked out too, though. It's rough on everybody."

Over the past two years, close to 40 percent of the employees at Cripple Creek Care Center have left, according to Cowan. He said the rural location coupled with the draw of higher paying travel nursing jobs has made it difficult to fill positions. The facility has increased recruiting efforts and worked with the local high school to get kids into nursing training, but, he said, that just wasn't enough.

"There's not really any staff member at the care center that has not worked double or triple duty," he said looking back over the past two years. "As an example, my business office staff are also certified nursing assistants.They're working one to two shifts a week to take care of the residents out on the floor."

No one, according to Cowan, has left to work elsewhere.

"The nurses that we've had leave over the last few years did not leave and go to another facility. They left for health reasons. They retired, or they just didn't feel like they wanted to stay in healthcare, or are moving out of state," he said.

Staff numbers really started to drop about six months into the pandemic, said Kellye Nelson, assistant director of nurses at CCCC.

"... and then of course the information about the mandates came down as far as the vaccines. And then that took another toll and, you know, we've just not had the applicants to replace that," she said.

Nelson largely blames the shortage on the COVID-19 vaccine mandates from the federal government. The care center did offer religious and medical waivers, but she said some staff still left.

Numbers from the state show just over 3 percent of workers at skilled nursing facilities throughout Colorado left their jobs due to the vaccine mandate.

On top of staffing shortages, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or CMS, is proposing a cut to home medicare funding, to the tune of $320 million. Nelson said that would be a big hit to providers with bottom lines already stretched thin, and especially challenging for rural healthcare facilities.

According to state data, the center did have three outbreaks starting last May. The outbreaks are considered resolved, but one resident died.

Still, Nelson said she thinks the mandates are a big part of the issue.

"COVID didn't close this facility," Nelson said.

"I feel like the government created this situation, not necessarily the virus," Nelson said. "Not that that's not really an issue, because it absolutely is, but for it to have gone, as far as it's gone, I personally think I'd rather be done with nursing."

And she's not alone. Research from the Kaiser Family Foundation shows the number of workers employed at nursing and elder care facilities has continued to decline nationwide since early 2020, while other health sector jobs have nearly recovered.

The Cripple Creek Care Center consistently gets high marks from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services or CMS. It's also been listed in the top 10 percent of health facilities in the U.S. for the past five years, as reported by U.S. News and World Report.

"I think that's one of the things that we've been very proud of is that we might not be new. We might not be fancy…but we're small and we care about the people," Cowan said.

That includes 86-year-old Marjorie Schmidt. She's lived at the Cripple Creek Care Center for the past three years, spending the day playing cards and bingo.

"I just want to pass time," she said.

Her closest family is in Denver - a few hours away. Henrich found her a spot at a nursing home in Cañon City, about an hour south of where she is now.

Cowan and other staff members have worked to soften the impact of the move for residents like Schmidt, visiting the new facilities with them, introducing them to staff and even helping them pick out furniture.

Another woman from CCCC is going to the same place as Schmidt, something she's looking forward to.

When asked if the closure is the right decision, Cowan wholeheartedly says "yes."

"I will never jeopardize the care that we give our residents," he said. "With the staffing numbers having decreased to the level that they have, that absolutely was a possibility had this decision not been made."

Neither Cowan, Henrich nor Nelson said they have made plans for what they'll do next. For now, the focus is on finding comfortable homes for the residents.