Lifelong residents of Pueblo can still remember the color of the Salt Creek more than four decades later.

“We called it the black water,” said Jovita Chavez on a recent morning from behind her desk at the Fulton Heights Community Center, a cornerstone of the Salt Creek community.

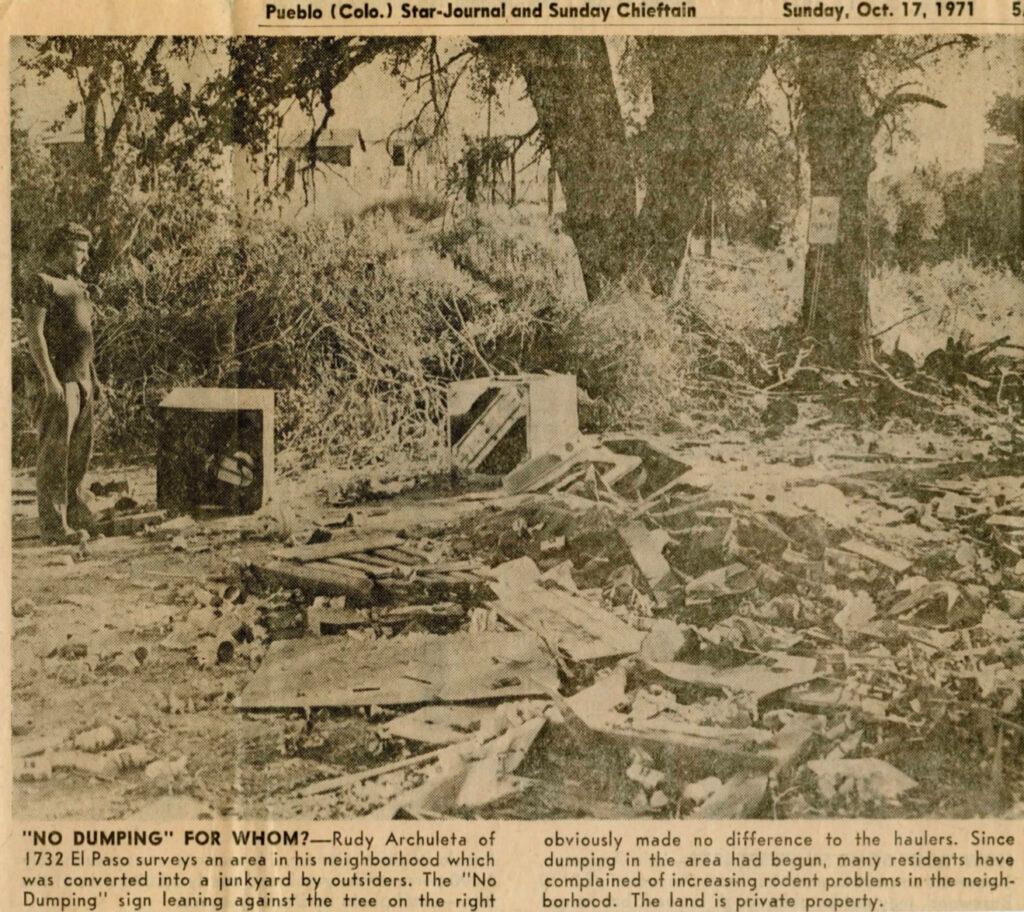

A 1971 article from the local newspaper, the Pueblo Star Journal, offered an explanation: The creek “runs black with oils” and chemicals from the Colorado Fuel and Iron Steel Corporation, an upstream steel mill that used the waterway to transport waste before it was treated and discharged into the Arkansas River.

Later that decade, the steel mill and what was then the Colorado Department of Health agreed to strip Salt Creek of its designation as a state waterway. Without it, the mill did not have to report pollution levels at the creek as required by the recently passed Colorado Water Quality Control Act.

Spurred by the historical neglect of the Salt Creek, environmental groups are now pushing the state to reverse course and restore its environmental protections.

The coalition, which includes local environmental nonprofit Mothers Out Front and law students at the University of Colorado Boulder, filed a letter with the department of health’s water quality division Thursday demanding it review the steel mill’s water discharge permit and give the public a chance to weigh in. Representatives for the mill’s current owner, Evraz, declined to comment for this story.

Court filings, state records and interviews with people involved in the creek’s downgrade and issuing the mill’s discharge permit characterize the arrangement as an exceptional deal made by the state for Colorado Fuel and Iron, the first steel mill in the western United States and at one time the state’s largest employer.

“We have an industrial legacy in this community of which we’re rightly proud, but we also have a legacy of environmental hazards and occupational hazards that need to be addressed,” said Velma Campbell, a physician and longtime Pueblo resident who volunteers with Mothers Out Front.

At the center of the creek’s decertification is a permit inspection conducted by a state hearing officer in 1978. His conclusion, according to the report: The Salt Creek is a natural intermittent stream and tributary of the Arkansas River that is fed by an "ancient, natural" drainage area.

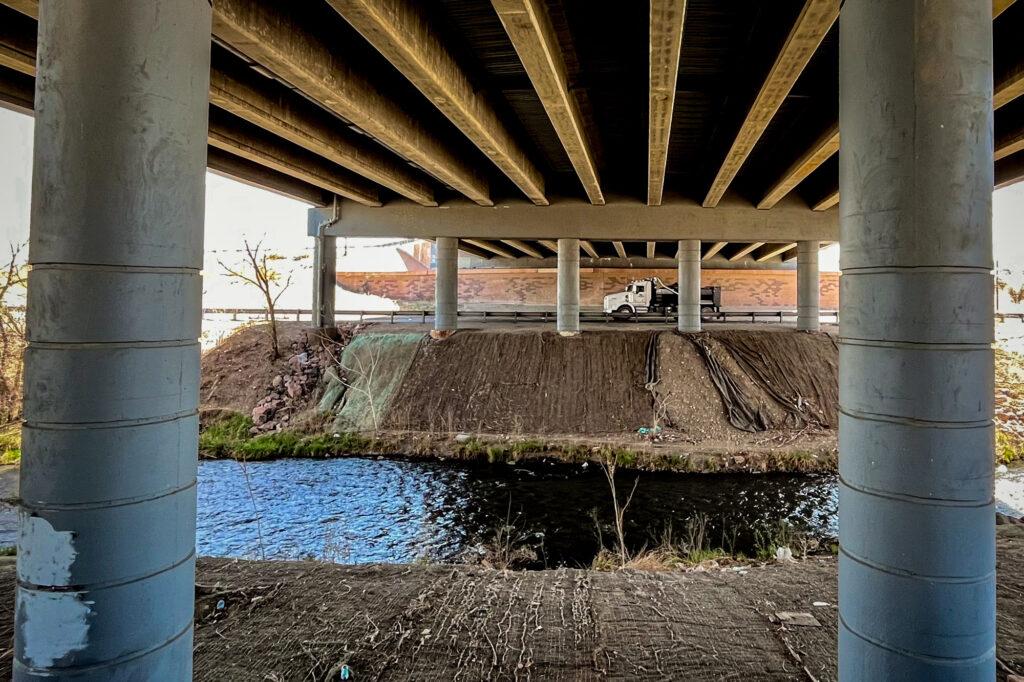

According to the hearing officer's report, the steel mill was discharging about 70 million gallons of water a day into the Arkansas River. The company brought that water from its reservoirs to the Salt Creek, which flowed in and out of the steel mill property. The water was then treated and discharged into the river.

After the formation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, the country began strengthening regulations on air and water pollution. Colorado passed its own water quality act in 1973. Along with the Salt Creek’s classification as a natural stream, the new rules meant the mill would have to fully treat its wastewater before it re-entered the creek.

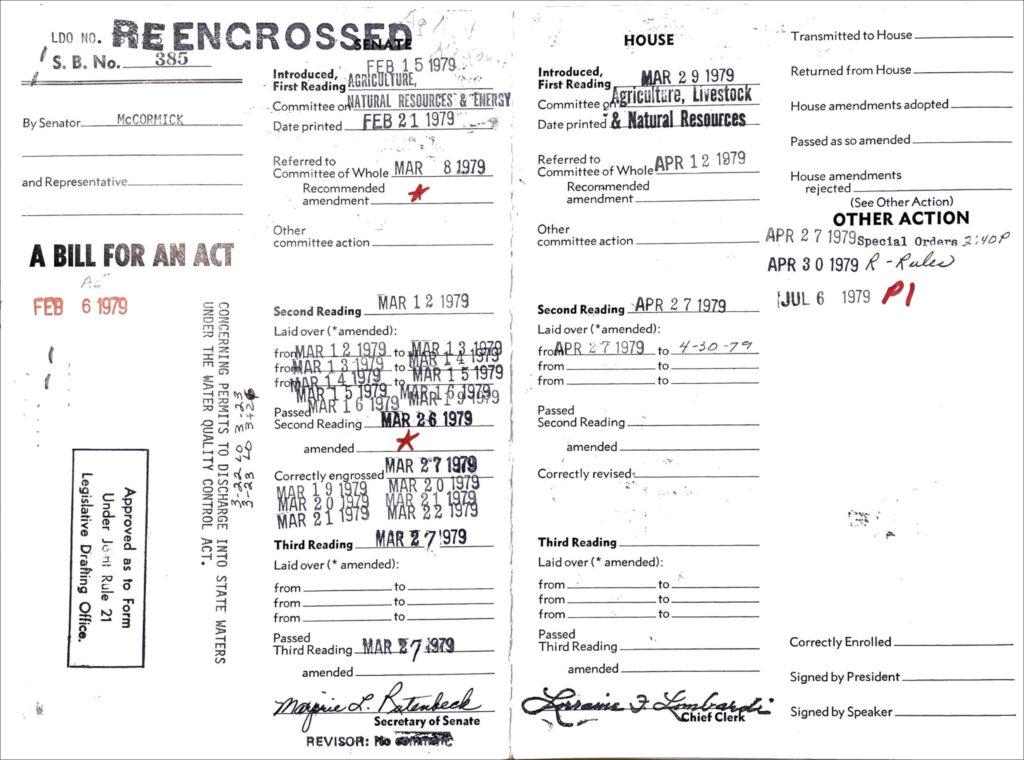

Colorado Fuel and Iron disputed this designation, pushing a bill by a Republican lawmaker from Pueblo that would have changed the state’s water discharge rules, said Bill Auberle, who oversaw permits as the state’s associate director for environmental programs.

Auberle said he and other state environmental officials feared the legislation would lead to unregulated dumping of wastewater in small streams across Colorado.

“It was a big uh-oh,” Auberle, now 77, said of the proposed legislation. “If this becomes law, then our responsibilities to the people of the state of Colorado, we thought, were going to be seriously compromised.”

That concern led to direct discussions with Colorado Fuel and Iron, he said.

In 1979, the state and the steel mill struck a deal. Officials reversed the hearing officer’s findings and downgraded the Salt Creek from a natural stream to a “channel,” according to state documents signed by Auberle. By losing its status as a state waterway, Colorado Fuel and Iron would not have to fully treat wastewater entering the Salt Creek.

The steel mill agreed to monitor cyanide, ammonia, and phenol levels in the creek, only some of the pollutants regulated by the state. The state extended the arrangement with current owner Evraz in 2018, nearly 40 years after the original agreement, records show. Its renewal caught Campbell's attention.

“If any company is going to be allowed to discharge their water products into the creek, they ought to be required, at the very least, that they’re not further degrading the quality of the water in the creek,” Campbell, 74, said overlooking the Salt Creek earlier this year.

A coalition of environmental groups sought help from students at CU Boulder’s Getches-Green Natural Resources, Energy, and Environmental Law Clinic to write a letter to the state, demanding it immediately review the mill’s water discharge permit and ensure water quality is protected in the Salt Creek. The reclassification of the creek was an environmental injustice, student Tess Udall said.

“[The creek has] been there for so long, … treated differently for so long, next to communities that are oftentimes left out of public conversation,” Udall, 31, said.

Over the decades, Salt Creek’s residents have complained of poor water quality, unrestricted dumping and lack of political attention paid to the rest of Pueblo. The community is primarily Hispanic and low-income, with a third of its residents making less than $15,000 a year, according to data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA data also show it's vulnerable to multiple environmental threats.

“We’re a forgotten little area,” said Chavez from the Fulton Heights Community Center, where she has worked most of her life.

Records show water entering the Arkansas River still has pollution problems. Records submitted by the mill to the state show several violations of the federal Clean Water Act in the last three years, including high levels of oil, grease and other substances in the water.

Colorado Water Quality Control Division spokesperson Erin Garcia said the state did not fine the mill for those violations. Division engineers inspected the mill’s wastewater treatment as recently as February, releasing a report recommending the mill add more absorbent barriers to soak up contaminants from entering the creek.

Garcia said the state wouldn’t review the mill’s wastewater permit until new standards for its basin become effective in December 2023. The state reached out to disproportionately impacted communities when renewing a similar permit for the Suncor oil refinery and would “plan to apply the lessons learned” to the Evraz permit, she said.

Campbell, a longtime environmental activist, said returning the Salt Creek's classification as a body of water would give the steel mill more responsibility for its wastewater discharge. At the very least, residents would be able to tell state officials their pollution concerns.

“The public needs to continue to stay on top of the data and enforcement to make sure that we’re getting the protection that the legislation intended,” Campbell said. “And it’s hard to do.”