Certified nurse midwife Bettyann Heppler avoided catching COVID-19 for two years. She is fully vaccinated and boosted. But after a recent trip to Utah, Heppler got pretty sick.

“Fever, body aches. I had really, really bad sore throat and ear pain and congestion,” the 57-year-old said.

Her COVID-19 test was positive.

“I was very surprised,” she said, “and I do feel like I let my guard down.”

Driven by a pair of super-transmissible omicron sub variants, more people like Heppler are catching COVID-19 and key coronavirus trends are heading in the wrong direction in Colorado.

Part of Heppler’s surprise is because she’d gotten boosted in late February. She said she was careful while traveling and wore a mask. Her hiking companion also tested positive. Heppler says the pair did share an AirBnb, though not the same room, and a car ride, which she thinks may be where she picked it up.

“I drove with her to a hike,” she said. “So I think it was in the car, me being in the car with her,” when she caught it.

Although Heppler’s illness is one anecdotal instance, her experience is becoming increasingly common.

The state health department warned on Friday that a new wave is already here, and is expected to land hundreds more Coloradans in the hospital, perhaps topping 500 or more hospitalizations in the next month. That’s according to a new statewide modeling report. The unvaccinated are most at risk — and Hispanic Coloradans and rural residents are the two largest groups with lagging vaccination rates.

“I do believe that we are starting to see an increase in cases associated with a new wave,” said Dr. Rachel Herlihy, the state’s epidemiologist.

Numbers only part of the picture

The state said the spike may place some strain on health care systems but not nearly to the degree experienced during prior surges. That’s because Colorado continues to experience high levels of protection from the most severe outcomes due to immunity from vaccination and previous infection.

But a lot depends on whether previous omicron infection is highly protective against the new highly transmissible, and surging, sub variant BA.2.12.1. In the worst case scenario, hospitalizations could reach 800, according to the May 12 state modeling report. That would represent a considerable surge, though it would be half of the peak of January’s omicron wave.

The positivity rate, the rate of positive tests, a rough gauge of transmission, hit almost 8 percent late last week, the highest level since mid-February as the huge omicron wave was receding. Last Wednesday the state recorded more than 2,000 COVID-19 cases, and the case rate climbed above 40 per 100,000 people — both were the highest numbers since mid-February, when the omicron wave was receding.

Those numbers are surely an undercount, as the vast majority of rapid home tests don’t get reported and are not reflected in the state’s numbers.

The state modeling report projects cases could more than quadruple from that level to above 8,000 a day, in a couple of weeks — so early June — and then start heading down.

The report estimates that under the worst case scenario, testing demand will peak at 45,000-50,000 daily test encounters. The state says it has the capacity to deal with that increased demand.

In the coming wave, Herlihy said, more people may get severely ill, though “the projections of hospitalizations are continuing to be quite a bit lower than what we've seen in previous large waves.”

The BA.2 omicron subvariant made up 73 percent of cases in the most recent data posted on the state dashboard, the week of April 17, The sub variant BA.2.12.1 accounted for 19 percent and another called BA.1.1.529 represented 7 percent of cases.

Small wave evident in some places

Others are noticing the uptick. “Yes, numbers are going up,” said Julissa Soto, an independent health equity consultant who works with the state to help vaccinate the Latino community.

Another sign of a coming surge is popping up in rising levels of the virus in wastewater. Take Durango for example.

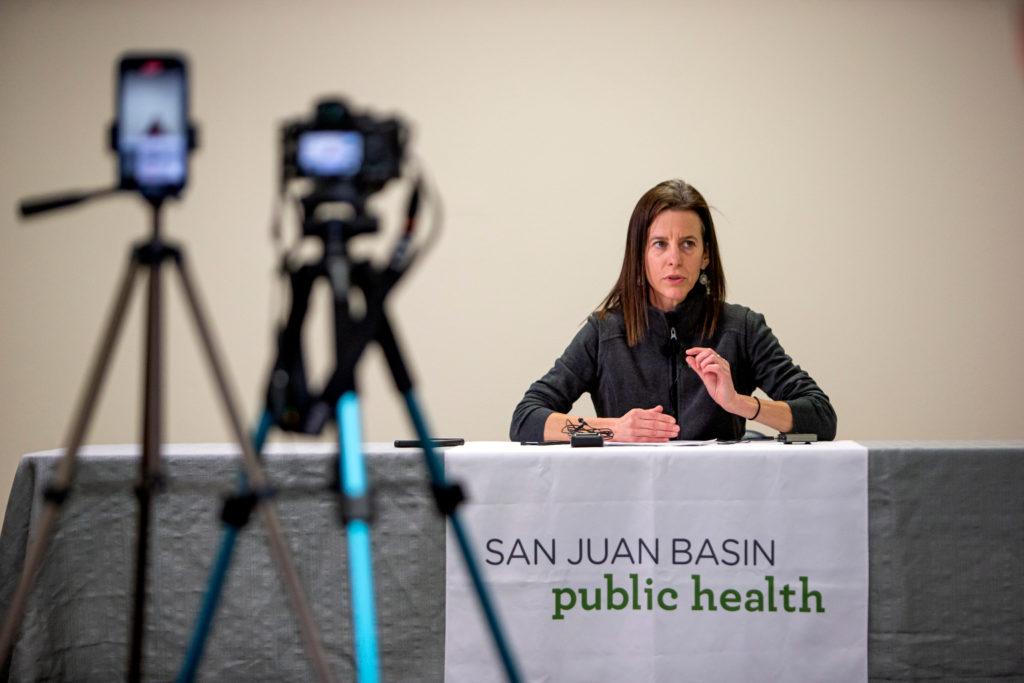

“Wastewater surveillance is really blinking red because it is showing an almost tripling of viral load in our wastewater,” over the last couple of weeks, said Liane Jollon, the executive director of San Juan Basin Public Health.

She urged residents, especially those at high risk for severe illness, to protect themselves and their families, by staying up to date with vaccines and boosters. Jollon said high risk and vulnerable people should consider wearing masks in public indoor spaces. She and her team are being more careful.

“We're doing things outside, we’re doing walking meetings, fresh air meetings. And then anytime we are meeting together, we have gone back to masking,” Jollon said. “I would absolutely mask if I were traveling.”

John Swartzberg is taking health safety precautions a step further. The infectious diseases doctor at Cal Berkeley recently canceled a trip to his granddaughter's graduation. Even though he and his wife are vaccinated and boosted, her ceremony was planned indoors.

Swartzberg said they were heartbroken, but it wasn’t worth the risk.

“I think the chances of my winding up in hospital with COVID, even though I'm 77, (are) really small, I worry about long COVID,” he said.

Much about long COVID’s lingering, chronic effects remain a mystery. But what’s clear is that higher levels of vaccination and prior infections are likely providing some immunity to many people, for now. He’s been watching Colorado closely and said it echoes national trends.

“Lots of people are getting infected either through breakthrough infections or through primary infections,” he said.

Swartzberg said he’s troubled that not enough Coloradans — or Americans or people around the globe — are vaccinated. It’s a concern others share.

'Let our foot off the gas'

“I am quite worried,” said May Chu, an epidemiologist at the Colorado School of Public Health. “We have sort of let our foot off the gas and we've sort of taken our eyes off monitoring and I think we're going to have emerging hotspots.”

She said a new variant could emerge that’s both highly transmissible, like the recent omicron sub variants, but also more harmful. And meantime Congress has yet to pass billions in new COVID-19 funds for vaccines, therapeutics, testing and research.

“I'm just worried, I have trepidation that we might be hit with a big one,” a dangerous new variant, she said.

For now though, Chu said, the good news is that current COVID-19 vaccines seem to clearly help prevent severe illness, hospitalization and death.

Nurse Bettyann Heppler says when she caught it, it was the sickest she’d been in years. Worse than the flu, but it didn’t result in a trip to the ER.

“No, thank God. I think because of being vaccinated and boosted, would be my guess,” she said.

Where Colorado stands with vaccinations

Seventy-five percent of Coloradans are vaccinated with at least two doses. But far fewer, just half of Coloradans, are like Heppler, protected with two shots plus at least one booster. To best fend off future waves — no matter the size — virus experts say the state needs to push those numbers higher.

Soto worries that not enough Spanish-speaking Coloradans are vaccinated.

“I am still seeing first and second vaccines. We are leaving my community behind,” she said, via email. “Everyone is talking about the fourth booster, and my community still struggles to get their first and second dose.”

Colorado Hispanics represent just 10 percent of Coloradans who have the first series, plus a booster shot, according to the state’s vaccination dashboard. That’s about half their share of the state population. Black Coloradans are also boosted at levels below their proportion of the state population.

Huge gaps exist between the state’s urban, suburban and rural counties.

Denver, several metro counties, and some mountain counties report more than 80 percent of residents 5 and up have gotten two doses.

The number is higher than 70 percent for other large Front Range counties: Jefferson, Douglas, Arapahoe, Adams and Larimer.

In El Paso County, it's 67 percent, Pueblo County is at 61 percent and, on the Western Slope, Mesa County, the figure is 54 percent.

Fewer than half of residents are vaccinated in many sparsely populated rural Colorado counties. In Kiowa, Rio Blanco, Cheyenne, Washington and Dolores counties the rate is below 40 percent.

Infectious disease experts say those wide disparities leave under-vaccinated areas and populations especially at risk to future outbreaks.