Early analysis from the Denver Regional Council of Governments suggests that its long-term transportation plan for the metro area will result in greenhouse gas emissions exceeding limits set by a new climate rule adopted last year.

DRCOG staff are in the early stages of exploring ways to meet those climate pollution reduction goals, including redirecting more of its budget to speeding up the installation of bus rapid transit corridors, building more multimodal projects like bike paths and lanes and sidewalks, and “refocusing the scope” of high-capacity urban arterial road-widening projects to emphasize users outside of vehicles instead of expansion.

And even those changes may not be enough, staff said, which means DRCOG will have to consider even bigger shifts in spending.

“I just want to warn you all, those will not be easy conversations [with local governments],” Ron Papsdorf, DRCOG’s transportation and operations director, told the agency’s Regional Transportation Committee on Tuesday. “We will rely on our partners to work with us on considering what mitigation measures are appropriate for the region — and that we can get buy-in from our partners to actually achieve."

Governments in the U.S. have long subsidized the automobile through things like single-family residential zoning, parking requirements and highway building. But now, with transportation accounting for the largest share of climate emissions in the state and a growing push to do something about it, that appears to be starting to change in Colorado.

If DRCOG doesn’t meet its targets of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 1.8 percent in 2025, 8.9 percent in 2030, and about 10 percent in 2040 and 2050 from an established baseline, the Colorado Transportation Commission can require local governments to spend certain state and federal money on projects that reduce emissions.

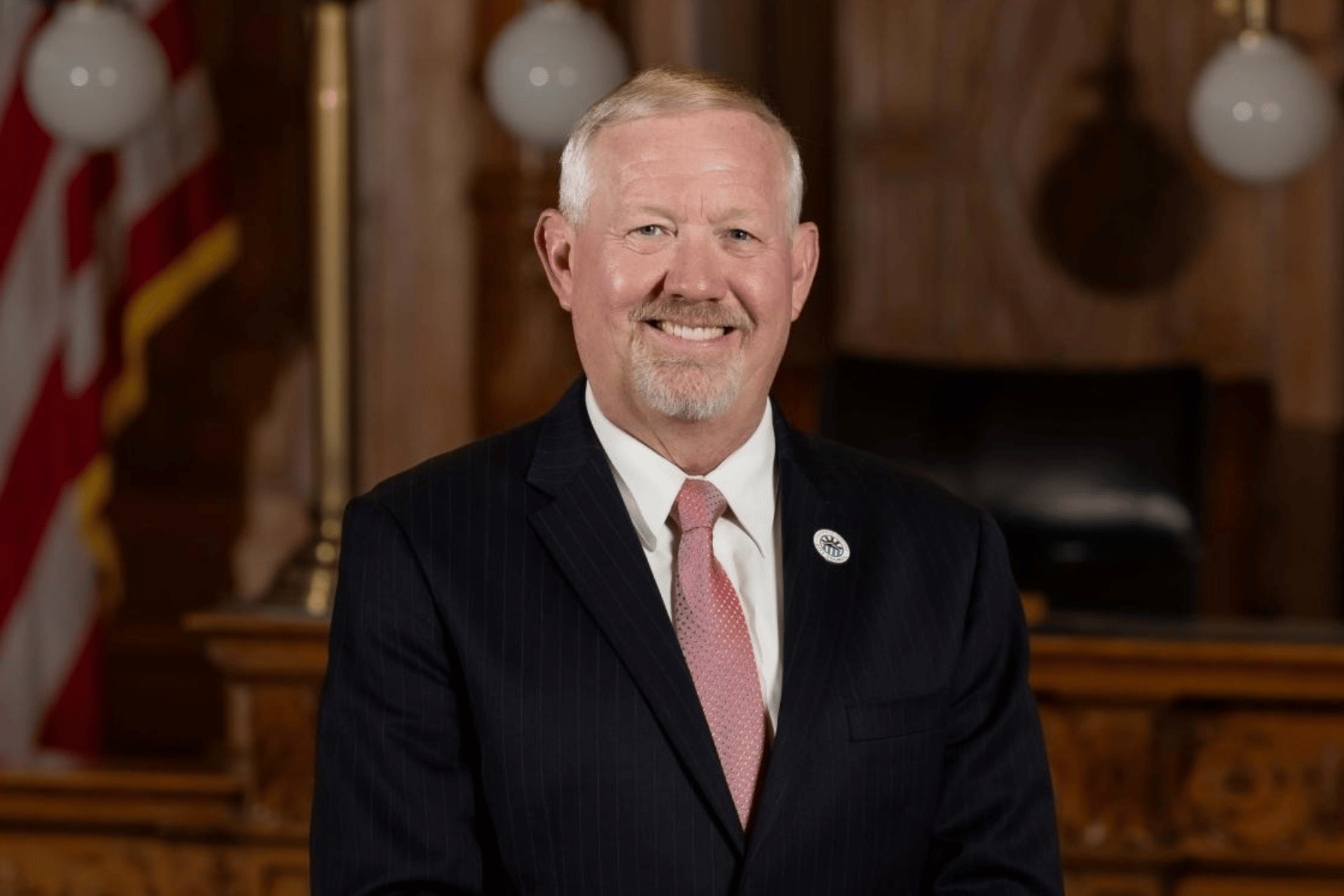

That’s exciting to Mike Silverstein, executive director of the Regional Air Quality Council and member of DRCOG’s Regional Transportation Committee, who noted that local governments have other goals and aspirations for cleaner transportation systems – but those lack an “enforceable mechanism.”

“And this greenhouse gas strategy that has been recently adopted requires it,” Silverstein said.

DRCOG’s long-term transportation plan, as it exists today, still includes major highway expansions like Interstate 25 south of downtown Denver, I-25 north of Denver, and I-270 in Commerce City over the next twenty-plus years. Some advocacy groups hope the climate rule will disrupt those projects, too.

“Colorado leaders can no longer pretend it’s possible to have it both ways — you can not continue to fund highway widenings that induce demand for driving while spending a marginal amount on multimodal projects,” reads a March letter signed by the leaders of 20 environmental, clean transportation, and neighborhood groups.

Still, some DRCOG Regional Transportation Committee members said it will be difficult to challenge the region’s car culture.

"We can do everything in this plan,” said Kevin Flynn, committee co-chair and Denver City Councilor. “But if the decisions made by 2.5 million individuals are different, according to their needs, if we don't understand their needs and their travel patterns, we're not going to hit those targets."

Such a shift may still need to happen among government officials, too. At the end of the meeting, DRCOG staff offered to validate parking for committee members.