A group of Latino moms in the suburbs north of Denver, many of whom work or volunteer in their children's schools, noticed many kids weren’t eating their cafeteria meals. A lot of food was wasted. The kids were coming home hungry.

“They were super hungry, like starving, so they started asking, what is happening? Are you eating or, or what is going on?” said Caro Neri, a community organizer with ELPASO Voz in Longmont, which is part of ELPASO, or Engaged Latino Parents Advancing Their Students Outcomes. It’s a community group that works on issues to improve children’s academic performance.

Other children ate the food and were struggling with obesity. Another thing they noticed: a big difference in what districts were serving students in their cafeterias. The students in Boulder and Louisville got fresh fruit and smoothies for breakfast. For students in Longmont and Erie — packaged banana muffins and breakfast pizza.

The women started investigating what was on the school menus in the St. Vrain Valley School District. They saw lots of processed and canned foods. They saw non-fat chocolate milk laden with sugar. There was fresh food to be sure, but they also saw preservatives, artificial colors or dyes, additives and high fructose corn syrup. Too much processed food wasn’t filling their kids up or they just weren’t eating school food.

“They realized that some kids didn't eat anything at all the whole day,” said Neri.

The group saw inequities: In the Boulder Valley School District next door, most of the food served is fresh and from scratch — prepared in-house using local ingredients — at the same or even lower price. Two years ago, the moms of ELPASO began pushing the St. Vrain Valley district to serve more fresh, organic food in schools. They put a year deadline on it. That’s come and gone. Wednesday night, they’ll hold a peaceful protest at the school board meeting, where several children will speak.

District says it serves organic produce whenever possible

At a February meeting with district officials, the women said the district didn’t agree with their calculation that 75 percent of the food is “ultra-processed,” consisting mostly of reheated frozen foods or made primarily from canned goods. The district, which declined an interview with CPR, told the women, it is doing a lot. In an email to CPR, the district said it serves local produce, including organic, whenever possible. Schools have a daily salad bar. The district uses chickens that are raised with no antibiotics and its chicken crispy patties have no artificial flavors or preservatives. The district said the 4 million meals it served this year meet or exceed USDA standards.

“When purchasing items, St. Vrain makes sure to choose items that are both nutritious and desirable to our students,” wrote Shelly Allen, the district’s director of nutrition and warehouse services, who is retiring this year, in a letter to ELPASO. “When configuring nutrition components for our meals, none of our food contain trans fats. Menu items must fall within USDA dietary guidelines regarding whole grain, lean protein, sodium, cholesterol, fat and added sugars.”

According to the district, fresh fruits and vegetables are available daily, and the menu includes food made from scratch most days. St Vrain’s menu includes nutritional data for each item.

A movement for fresh, organic food borne out of research

Before they could make requests of the district, the women needed facts. They learned how to research: What was a colorant? What was monosodium glutamate? How were “added” sugars different from sugars? And was all this really necessary to put into school children’s food?

“If you want that carrot to look cute and fresh when you open the package, it's full of crazy colorants,” said Tere Garcia, executive director of ELPASO.

Then they wondered, it’s got to be more complicated than we think. What’s it like to cook for thousands of kids? They interviewed chefs and nutritionists, visited farms and cafeterias, read books and watched documentaries.

They learned that Boulder Valley Schools had started shifting to healthier food more than a decade ago with the hiring of Ann Cooper, known as “The Renegade Lunch Lady,” now retired. They got in touch with Boulder’s new chef who invited them to the district’s specialized culinary center.

The two neighboring districts have roughly the same number of students. About 20 percent of Boulder Valley’s population is eligible for free and reduced-price lunch while 27 percent of St. Vrain Valley’s is. Comparing how much each district spends on food service is tricky as budgets fluctuate with how many kids participate in meals, food costs, how much districts pay workers and the raises they get. While the state’s financial website shows the district’s having roughly the same food service budgets, the tool doesn’t capture additional grants and money from a district’s general fund, which Boulder receives. Many districts don’t allot general fund money for their food service departments. Scratch cooking can be more expensive and labor intensive.

And the women quickly learned that serving healthier, fresh meals is an immense undertaking. Boulder Valley has a 33,000 square foot centralized kitchen. Voters approved a bond in 2014 to pay for it. The St. Vrain district would need specialized kitchens and training. But, the women thought, it was a worthy goal.

“Now we know what we want,” said Garcia. “We want fresh food cooked from scratch. If we are going to feed the students in any district, it needs to be good food.”

“What motivates you to be here, ladies?”

Karla Cardoza asked the dozen women sitting around a conference room table what brought them to an ELPASO meeting. Everyone says they want a better future for their children.

“I don’t know exactly what they’re eating at school but I was sure it was healthy food until my friend said I was wrong, that I should pay attention to what they’re eating,” said Araceli Compean, mother of three. “I was surprised to learn there is so much processed food served.”

The group had two main demands: that 75 percent of ingredients on recipes are fresh and made from scratch within one year, and that the menus are made with at least 80 percent organic ingredients.

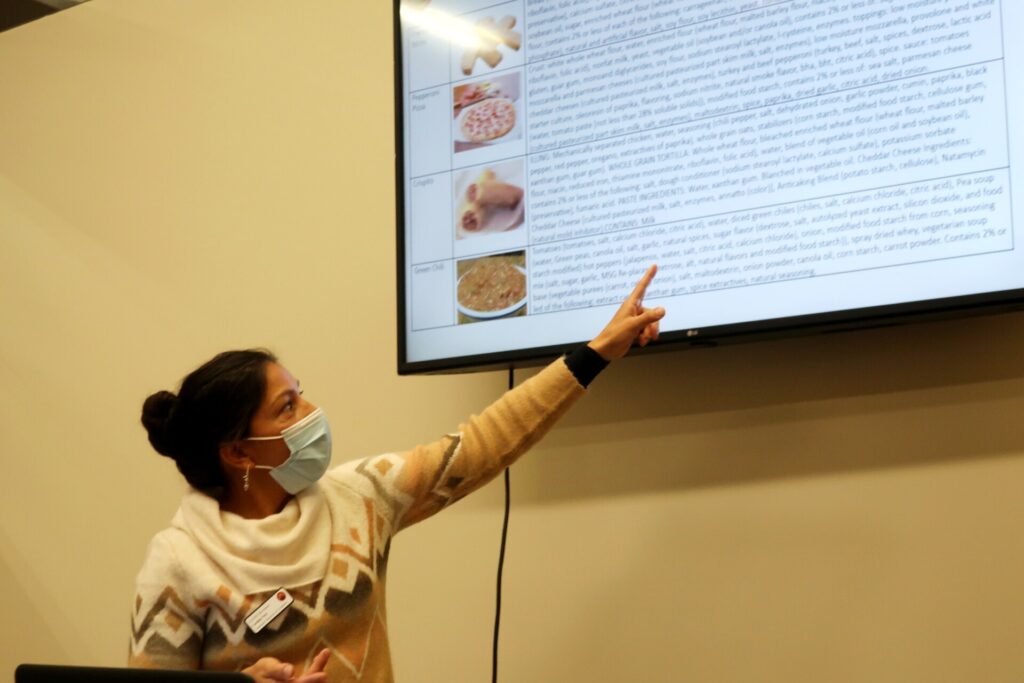

At the meeting, they presented a slide show showing each of the menu items.

“Children love them but what do you think, is it a processed or fresh product?” asked Cardoza, showing a picture of a Crispito, a cooked chicken and chili flour tortilla snack product from Tyson.

“Processed,” the women called back. Cardoza points out the product’s long list of ingredients.

They go through the menu items, talk about what’s healthy food, describe various additives and preservatives, and their trip to the Boulder district’s kitchen facility.

“It was super impressive,” said one woman who talked about the huge equipment used to make fresh food. “They had a massive blender, that's where they mix the dough to make the bread for the hamburgers … and their students are almost the same students as St. Vrain’s."

The women talk about how high cholesterol, obesity and diabetes is a problem, particularly among Latino children. One mother, Maria Valdez, told the group she wants artificial food dyes out of St. Vrain’s food. Some studies have shown they can aggravate behavior problems. Her son has battled high cholesterol and triglyceride levels for years.

“We made an agreement with the doctor that we were going to try to bring food from the house for his lunch and stop eating at school,” she said. She followed through and her son’s cholesterol levels have dropped.

Group wants district to take small steps

The district meanwhile, said it is committed to creating balanced and nutritious meals, according to a letter nutrition and warehouse services director Shelly Allen wrote to the ELPASO. In a single school year, St. Vrain provides more than 900,000 pounds of local produce in its cafeterias, she said.

She said the district educates students on healthy eating and has offered classes to educate parents on healthy eating on a budget, offered cooking classes to underserved communities and hosted student-led farmer’s markets. A grant will allow nine schools to grow produce for their school cafeterias.

While the women say the district hasn’t accepted their requests, ELPASO hopes the St. Vrain district will start with small steps. For example, serving chocolate milk only on Fridays. They’re concerned about the “fat free” chocolate milk. On the box it says 18 grams of sugars (6 grams of added sugars, which are not naturally occurring.) But the school menu leaves off sugar content for both white and chocolate milk.

The women say they want to work with the district. They realize what they’re asking for is a total structural change in the way food is procured and cooked, that would likely require more money for culinary improvements to be on a future local ballot.

ELPASO’s Tere Garcia would like to see the same kind of commitment.

“They have to eat well in order to learn,” she said. “Children need good food, so we’re going to get it.”

The organization is hopeful St. Vrain Valley’s incoming food service director will share their vision.