While he has long dealt with depression and anxiety, Joshua Hursa’s major mental health symptoms didn’t appear until he was 25. And the first time they did, they were devastating.

Hursa was on a walk with his three-year-old daughter through a park in Denver when “I slipped into a psychosis. I didn't even know that she was there.”

Hursa made his way to the Brown Palace Hotel, somehow becoming separated from his daughter. Security videos show him talking to people he saw and heard, but who didn’t actually exist. His daughter was later found outside unharmed.

Doctors diagnosed Hursa as bipolar with psychotic symptoms — he’s since been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, which Hursa said manifests as having three personalities inside of him. He also struggles with trauma from being raped as a child by his grandmother, who now reappears as one of those personalities.

“I have multiple people in my head who are, like, either yelling or screaming or trying to control my body at any given time,” he said.

After being arrested for the incident, Hursa was sent to a mental hospital for seven days and then to jail. He pled guilty to reckless endangerment rather than deal with a child felony abuse charge.

“She remembers it,” he said of his now 10-year-old daughter. “She'll cry sometimes about it, but she wrote a very nice letter to the governor asking for a pardon. So I think she's okay with it at this point.”

Thus began Hursa’s journey with the state’s mental health and justice systems. In the seven years since, he’s been hospitalized twice, and had to spend two months in jail when there wasn’t any other place for him to go. He is currently on probation for an incident in 2020 in which he was charged with felony menacing and impersonating a police officer.

He described managing his disorder as similar to working through a complex math equation, juggling all these different variables to come out at normal.

“I take six different drugs,” Hursa said during an interview with CPR. “Before I came here, I popped all my pills, but it's a choice. I can wake up and be a homeless schizophrenic any day of the week.”

Despite the daily challenges, Hursa in some ways considers himself lucky, compared to others with his condition. He’s not behind bars, or living on the streets. For now, he’s managing his symptoms and they don’t appear to be getting worse.

CPR sat down with Hursa earlier this spring in an empty hearing room at the state Capitol. Outside, the bustling work of the legislative session was in full swing. This is a place he knows well; he spent four years working at the statehouse as a Republican legislative aide, and had long been engaged in politics, serving as the head of his college’s Republican party, and joining the Denver Metro Young Republicans.

“So I had a whole career, basically, prior to my symptoms,” he recalled.

This year Hursa was back at the Capitol in a new capacity — to lend his support for a historic package of mostly-bipartisan behavioral health bills that lawmakers ended up passing. At close to a half billion dollars, it is the largest single-year investment lawmakers have ever put into behavioral health in any legislative session. Much of the money comes from federal COVID relief funding.

For Hursa, this is a long-overdue investment from a body he feels has too often failed to prioritize care for people with mental illness.

“We deprive these people of a normal life and we'd make them into second class citizens that we don't care about and it's wrong. It's totally wrong,” he said.

Many of the bills were proposed by a bipartisan task force, convened during the legislature’s off season last year to develop proposals for the most effective use of funding to address what many at the statehouse have come to agree is a crisis.

Democratic Rep. Judy Amabile of Boulder sat on that panel and ended up spearheading much of the legislation. It’s an issue of vital personal importance for her; she was spurred to run for office in part because of her family’s experiences after her son was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder.

“It's just important for us to keep that in mind as we move forward — all the bills and the money that we're spending this session, it's meaningful, but it's not the final solution,” Amabile said.

Among the big proposals Gov. Jared Polis has signed or is expected to sign into law:

- Adding more capacity for mental health patients, both adults and youth, who need full time residential treatment.

- Streamlining behavioral health administration to try to make the entire system more efficient and transparent.

- Increasing availability of competency restoration services for people in the justice system, and creating new avenues to divert people with behavioral health problems or substance use disorder into treatment, instead of jail.

- More funding to support youth and families and schools.

- Beefing up the state’s diminished health care workforce, including behavioral health, in the wake of COVID.

- Providing grants to behavioral healthcare providers to try to fund gaps in the current system.

Behavioral health advocates say in many ways Colorado has nowhere to go but up. According to recent figures from Mental Health America, the state ranks last in the nation in access to care compared to prevalence of adult mental illness. It does slightly better when it comes to youth.

And they only expect the pressures on the system to grow, as people continue to endure stress, anxiety and disruption coming out of the pandemic, coupled with increased tensions around political and racial divisions.

“We have had some of the nation's highest rates of adult and youth suicide. We've got an opioid epidemic on our hands,” said Vincent Atchity, the President and CEO of the non-profit Mental Health Colorado. “So we're in a critical condition on the extreme side of things in so many ways.”

A focus on care for the most serious cases

In recent sessions, lawmakers have focused on addressing Coloradans’ mental welfare generally. A recent program allows all school aged youth to get up to three free counseling sessions if they want. In 2021, lawmakers successfully pushed for health insurers to cover annual mental wellness check ups

This year’s package, however, was more targeted at those in crisis and with more severe needs.

The lack of those services is something Sylvia Tawse and her family have dealt with directly. Tawse describes her son, who had his first psychotic break when he was 15, as suffering from “a bad mashup of schizophrenia and bipolar.”

She said the diagnosis came as a shock to their family because he was creative and a top student, a boy who loved sports and competed nationally in skiing.

“What we saw was this vibrant young man, still a teenager, go into a deep, deep, deep depression, almost comatose-like. His first hospitalization he slept for nearly a whole week,” she recalls.

In the years since, her son has gone through more than 22 hospitalizations. Tawse said the biggest challenge has been finding places where he could get longer term treatment in a safe, contained environment, instead of just cycling in and out of hospitals for short stays.

“We have an anemic level of behavioral health beds,” said Tawse of Colorado. She and her husband depleted their savings and refinanced their house twice to send their son to a private facility out of state. “We have about the same number of beds as we had in the 1970s.”

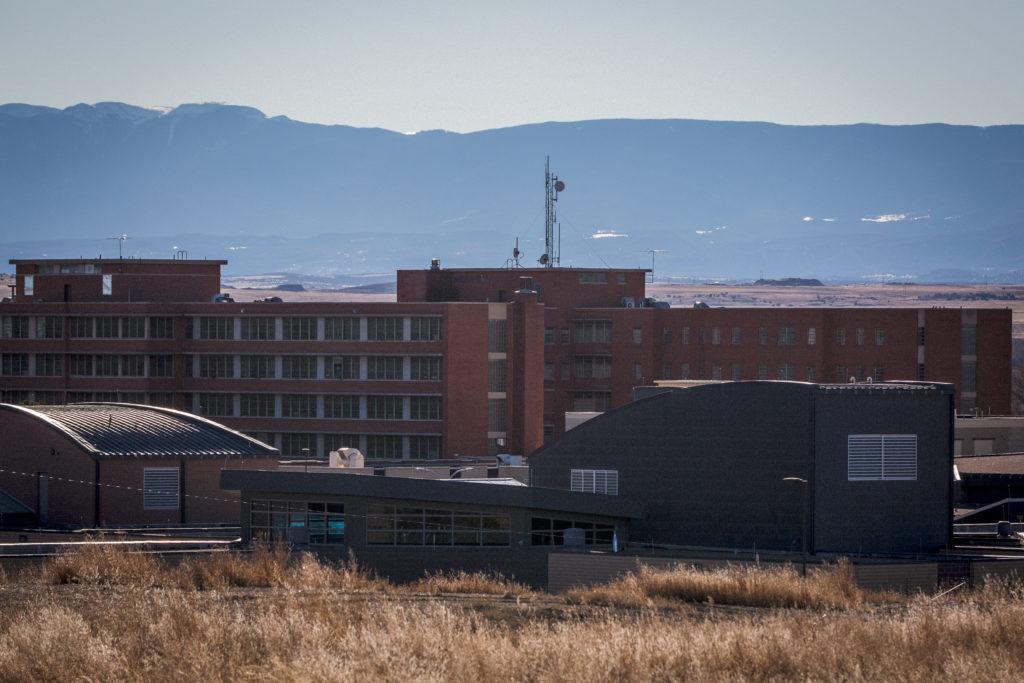

The situation reached a crisis point last year; her son stopped taking his medications and ended up in the ER. From there he was moved to a hospital in Colorado Springs, which prepared to discharge him after less than a week.

“I literally pleaded, said, ‘you know, I don't think you've seen his mania. If he's been sleeping most of the time, then you haven't seen him cycle into mania,’” Tawse recollects. Her son’s mania, she said, makes him agitated and threatening.

Tawse had been told that in a few days a spot might open up at a 30-day residential program in Pueblo. But instead of holding the young man until it was available, the hospital released him.

Three days later he had made his way to his parents’ house in rural Boulder county. Tawse said when he arrived he was barefoot and sunburned and hearing voices.

“I knew he was psychotic and completely detached from reality,” she said. “I offered him a glass of water and tried to reach for my phone. And he took my phone and he smashed it under his feet. And then he proceeded to assault me.”

She said that’s the first time her son was ever physically violent with her. She left in an ambulance and he was taken to jail, where he has now been for over a year waiting to regain competency so he can stand trial.

“Our son currently has three felonies charged against him and that could equate to as many as 30 years in prison,” she said. “I don't even know how to put a cost on that.”

Tawse believes with more behavioral health beds and options for people like her son to receive longer-term care, his situation wouldn’t have escalated like it did.

To start making a dent in that shortage, Gov. Jared Polis has signed HB22-1303 from Rep. Amabile that puts $42 million to opening at least 125 new residential treatment beds around the state.

“The vision for this is that it's a place where you could stay for a week, a month, three months, six months. And that how long you stay should depend on what you need, as opposed to who's paying and how much they're willing to spend, which is kind of the system we have now,” said Amabile.

Even though the bill doesn’t completely eliminate the backlog and delays in people’s ability to find a bed, Amabile said it’s a strong start.

“I'm feeling optimistic that we're going to make some change and that we're going to help some people and improve on our mental healthcare system.”

Mental health and the criminal justice system

The situation for Tawse’s son also illustrates another problem the state has long struggled with — how to help people with severe mental illness who end up in the criminal justice system.

For more than a decade, Colorado has faced lawsuits and fines because it has consistently failed to get people who are deemed incompetent to stand trial into treatment in an adequatee period of time. One major reason is that the Colorado Mental Health Institute at Pueblo doesn’t have enough beds or staff to treat all the people who need it.

Boulder County sheriff Joe Pelle has seen the percentage of mentally ill people in his jail increase exponentially over his two decades on the job.

“We have, sometimes, 50 inmates waiting to go (to competency treatment), who are kind of languishing in the jail for months,” he said.

What mental health services the county is able to provide in the jail are generally just focused on stabilizing people in crisis, not helping them get significantly better.

Some of the new residential treatment beds from HB22-1303 are initially slated for competency restoration treatment until that backlog is lifted. At any given time about 350 people in jails across the state are on the waitlist for competency restoration, according to the court monitor for the legal case.

Another measure meant to help improve the situation would let people facing misdemeanors get restored to competency in outpatient settings, instead of waiting in jails. It also has money, about $30 million, for new inpatient beds. The governor has also signed new laws intended to keep people with behavioral health problems out of the justice system, and to expand a pre-trial diversion program for those who are arrested to get into community treatment.

Pelle is hopeful these new laws — and the money that comes with them — will make a difference; he’s the first to say jail offers limited tools.

“Jails were designed for security and safety concerns and not as therapeutic offices or buildings or hospitals. So we are doing the best we can with what we have,“ he said.

Amabile said the criminal justice piece — treating the most vulnerable populations and the most overrepresented demographic in jails — is a critical part of the entire package of new legislation, and will also help ease pressures on other parts of the behavioral health care system.

“These are the people who we absolutely, desperately need to help,” said Amabile.

Mental health and youth

This session also saw lawmakers agree to put significantly more funding toward filling in gaps in programs and services for children and families.

This comes a year after Children’s Hospital Colorado declared a Youth Mental Health Emergency and on the heels of new investments last year as well. The hospital cited the devasatating statsitic that suicide has become the leading cause of death for young people in Colorado, and that their emergency rooms are seeing more and more young people who have made suicide attempts.

Democratic Rep. Dafna Michaelson Jenet has spent her years in the legislature focused on increasing mental health care for young people. She was the main sponsor of a bill this year to pump millions of dollars into residential respite care for children, and build a new neuro-psychiatric facility for youth at the state’s mental health institute at Fort Logan.

“One of the things that we're building out is the continuum of care,” said Michaelson Jenet. The goal is to make sure young people aren’t being discharged from intensive residential care to home because there’s nowhere else for them to go. “Then they wind up back in the emergency department because stepping down from the hospital to the street was not a safe progression.”

Michaelson Jenet also made sure her legislation included provisions to create treatment beds outside of hospitals that will serve youth with multiple issues occurring simultaneously, such as substance use issues and mental health disorders. But she warned it’ll take a while to see the on-the-ground impact of these wide ranging policies.

“I'm an eternally optimistic human being and I really believe that the bills that we are bringing forward, slowly but surely, are going to make the impact and inroads we need in this state,” she said. “I think that we'll turn around in five years and look back, hopefully, at the mental health landscape of Colorado and be able to see the impact (that) everything that we have been doing has seeded.”

While advocates are pleased with all the new investment lawmakers have put into the state’s strained mental health care system, they also worry about the pace of implementation. Vincent Atchity, the president and CEO of Mental Health Colorado, notes that new government programs and facilities often come with a lot of red tape and move at a glacial pace.

“My concern, as the consumer advocate, is more about the urgency of now and the lives that are in jeopardy now,” he said.

A bipartisan reach for systemic change

Another unique aspect of this huge package of legislation is the strong bipartisan support many of the measures received from lawmakers.

“I wanted to make sure rural Colorado had a voice,” said Republican Rep. Rod Pelton of Cheyenne Wells on the Eastern Plains about why he agreed to serve on the behavioral healthcare task force . He supported many of the measures, such as Michaelson’s Jenet’s bill on increased money for youth treatment.

Peton said the challenge is often greater in rural areas because they are more remote and there aren’t as many places to get treatment. Also, he said social stigma can be an additional barrier for people who need help.

“We have an attitude that we can accomplish anything on our own. People in rural Colorado are very independent,” he said.

Atchity, with Mental Health Colorado, said one thing he’s been grateful for in recent years is that people are increasingly open about their mental health struggles, and more are thinking about it than ever before.

“Employers are much more thoughtful about wellbeing in the workplace and things like that,” he said. “This is how human communities solve problems, is that they bring them to awareness and they discuss them more widely, and so there is some cause for optimism there.”

As just one example, Colorado is putting more money for mental health support for those who have stressful jobs in the criminal justice system. The new law sets aside a half million dollars for counseling services, as well as training to recognize and treat job-related trauma, for professionals on both sides of criminal cases.

Michaelson Jenet said she thinks everyone, no matter their job or circumstance, needs to evaluate their own mental health and treat it as a top priority, no different from exercising and eating right for physical health. She said this moment in time is especially challenging.

“As far as the mental health of everyday Coloradans, we have all been traumatized in one way or another by COVID. Whether or not you wanna see yourself as traumatized (is) totally your deal, but we have all been impacted by COVID,” she said.

To try to pull all these resources together, Colorado is also moving to set up a new Behavioral Health Administration aimed at streamlining services and funding for mental health and substance use. The goal is to make the system more efficient and easier for families and professionals to navigate and find care that is accessible, affordable and equitable.

Rep. Amabile knows firsthand how hard the current system can be to navigate, from her own family’s struggles to get help for her son.

“We just didn't know who to call. We didn't know the lingo. We didn't know the difference between detox and rehab. And we were handed lists… ‘here's 10 places that you could call and see if they can help you.’ And you know, none of them worked.”

Under a newly signed law, the Administration has a year to set up new systems to oversee and integrate the state’s behavioral health resources and make it easier for people getting treatment to file complaints about problems.

“That consolidation should help provide more direct access to care and services for the people who need them,” said Atchity with Mental Health Colorado.

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to correct where Joshua Hursa was arrested.