Taha Dakkak’s old roller hockey jersey still fits him like a glove.

Dakkak was showing off his old threads during a recent visit to his window tint shop in Denver, Tint My Ride. The jersey’s emblazoned with a fierce cougar clawing at a hockey puck, representing Aurora’s Cherokee Trail High School, where he graduated from 11 years ago.

“What made hockey exciting for me was skating and going really fast,” Dakkak said from his office. “I loved the roughness of it. I was able to stay healthy and fit playing hockey. My wife always comments on my butt and I tell her it’s from hockey.”

Dakkas’s done tint work for Colorado Avalanche players’ vehicles in recent years and has a signed jersey from a former Avs player displayed in his office. He loves hockey. But he also remembers struggling as a Muslim youth, playing a sport where he was regularly subjected to people’s biases and racism.

“The kids that I played with, they would make racist comments,” he said. “My mom came one time to practice and she heard some really rude comments and after that she never came to any of my practices or games.”

When asked about the slurs, Dakkak said, “Terrorist, middle fingers, ‘Go back to your country,’ basic hate that everyone says.” For the record, Dakkak’s country is the United States. He was born in Kansas after his parents immigrated to the U.S. from Syria.

“At the end of the day, I’m American and I love America just like anybody else living here,” Dakkak said. “Just because my parents are from Syria and I speak Arabic doesnt make me any less than any other American.”

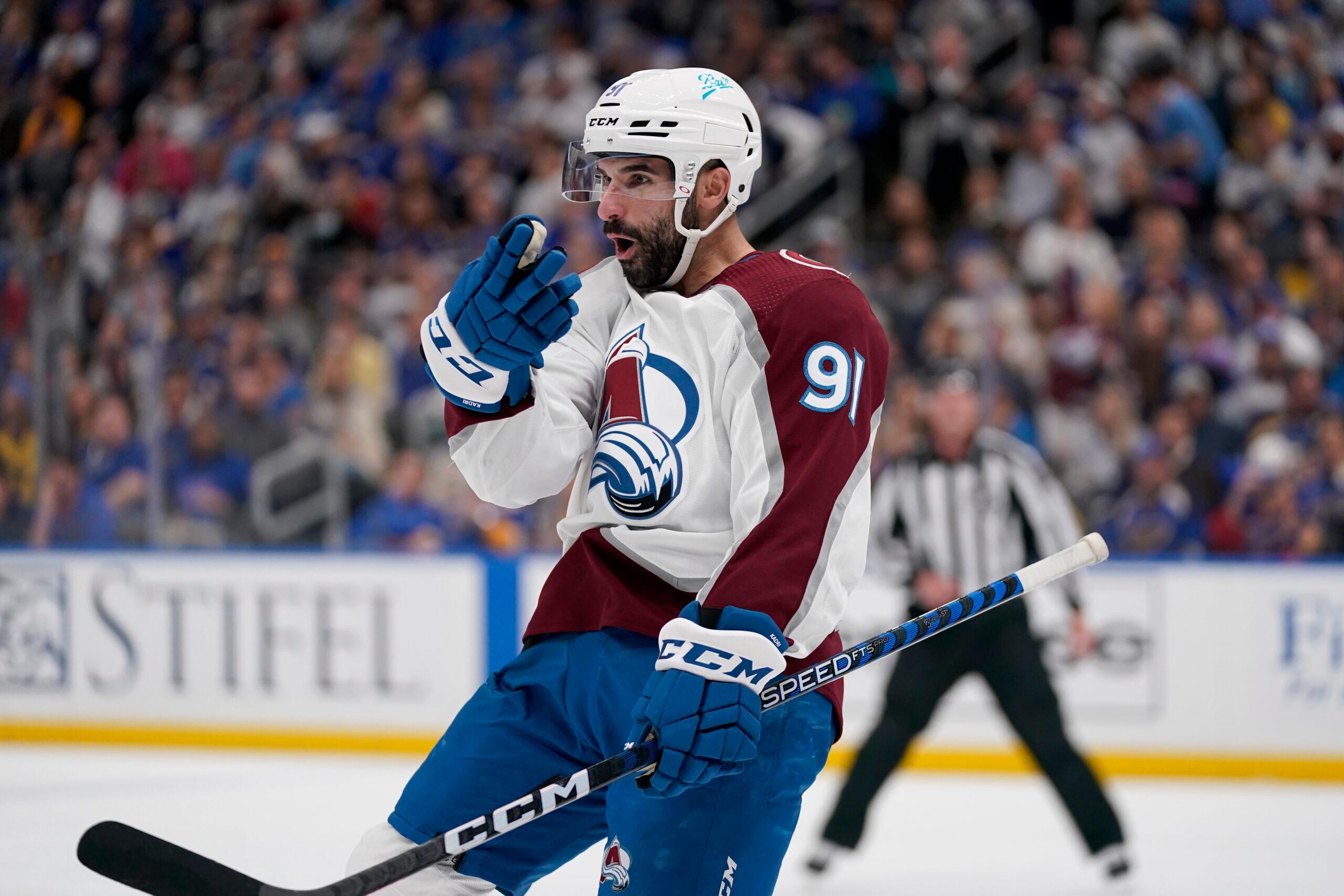

Dakkak said the prejudice he often deals with is dejecting. But something that’s giving him hope these days is Colorado Avalanche center Nazem Kadri, who is Canadian, but with parents from Lebanon. Kadri is also Muslim. And as the Avs get set for a crucial game six against the St. Louis Blues, Muslim hockey fans like Dakkak are bracing for another round of hate directed at their hero.

“I can’t imagine how hard it would be,” Dakkak said. “He’s the only Muslim in the whole NHL and then having to go through that, I respect him a lot though. It really does inspire me to be brave, he’s very, very brave.”

It was a now infamous incident on a Saturday night in St. Louis where Kadri became public enemy number one among Blues fans. He was going for the puck in front of the opposing team’s net when he and a Blues player crashed into St. Louis goalkeeper Jordan Binnington, who was injured and will not be able to play the rest of the series.

Referees didn’t call a penalty on the play and the league did not punish Kadri’s actions. But that didn’t stop some Blues fans from attacking Kadri’s race and religion on social media. Kadri’s wife posted some of the comments directed at her family on Instagram, with people calling her husband things like a “stupid Arab.” One person even questioned where Kadri was on 9/11.

“Unfortunately I’ve been dealing with that for a long time,” Kadri said following Monday’s game in St. Louis. “That’s sad to say, but I’m getting good at just putting it in the rear view mirror. It’s a big deal, I try to act like it’s not. And just keep moving forward.”

Kadri let his play do the talking that night in enemy territory: He scored a hat trick to lead Colorado to victory.

“For those that hate, that one’s for them,” Kadri said after the game.

For other Muslim athletes, people’s hate has them asking ‘Why?’

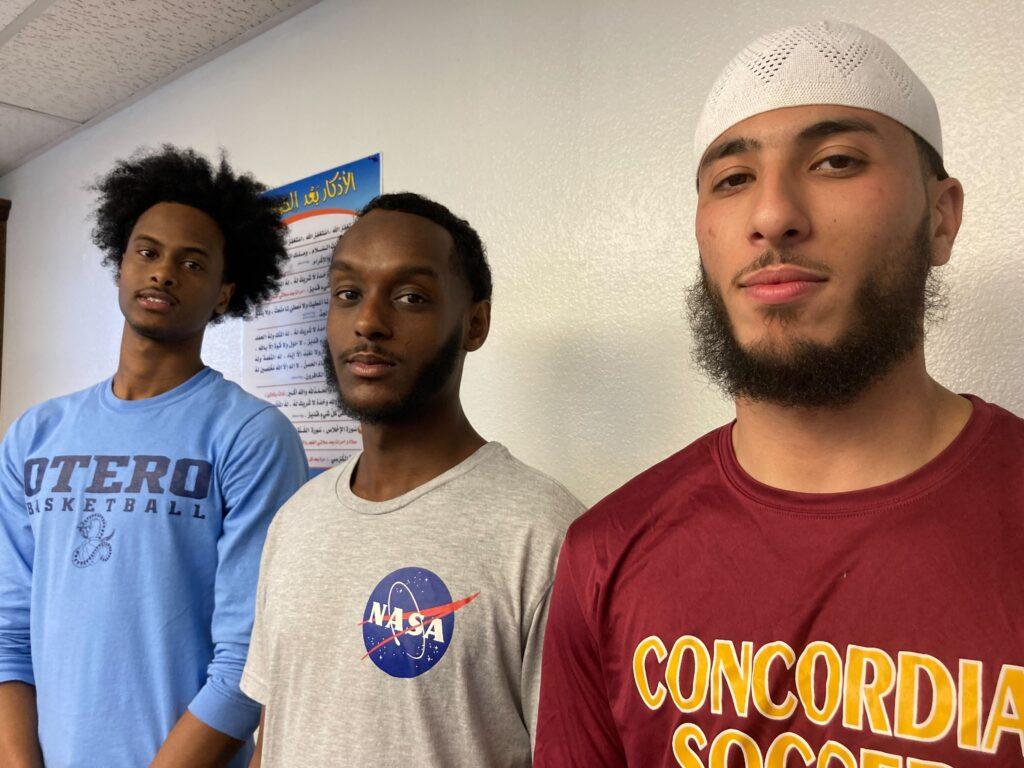

The kind of hate Kadri’s dealing with is something Albara Mutleq can relate to. The 21-year-old Colorado native and Muslim currently plays soccer for Concordia College in Minnesota. He remembers a playoff game in high school when someone on the opposing team called him a Muslim slur. But he says the referee didn’t do anything about it.

“It wasn’t the first time that it happened,” Multeq said. “I dealt with other stuff that whole season. And after that incident happened, I took my jersey off, my captain badge off, and I told my coach, ‘If you're not going to do anything about it, I will not play this season.’ And it cost me my whole season.”

“It just hurts, you know? Like, at the end of the day, nobody cares.”

Multeq is a member of the Islamic Outreach Center in Denver, where Shafi N. Aziz is the imam.

“If we start hating people because of their faith or hurling all these insults at young people like this, then I'm saying where is the future?” said Aziz. “And we are giving opportunists a chance to destroy the world.”

Aziz says attacks on Muslim athletes have been a sad reality for decades, from Muhammad Ali to Kareem Abdul-Jabar and locally, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf. Rauf, who played for the Denver Nuggets in the 1990s, angered some fans for protesting against oppression by refusing to stand during the U.S. national anthem. In response, four Denver disk jockeys from KBPI marched into a metro area mosque, playing the Star Spangled Banner on trumpets and horns.

“When you see a man like this (Abdul-Rauf), someone of amazing standards, and you hear about what he used to face, it’s something really sad. It just shows how cruel people can be,” said 21-year-old Kamal Mahamed, a Colorado-raised Muslim who has met and looks up to Abdul-Rauf. “How could a person be this rude because of someone’s skin color or because of their religion, or because of whatever other things God has instilled them with?”

Aziz also condemned the attacks on Kadri.

“Why do we do that? This is just a young man whose parents traveled from their native home for a better life, like any other person. This person should be appreciated, encouraged, this young man should be loved. He worked so hard to earn what he has earned. What is his crime? What is his crime?”

Players, coaches … and fans 'Stand With Naz'

But a lot of people have Kadri’s back. Avs players and coaches have denounced the attacks while praising his performance in the playoffs. And many fans at Wednesday's game in Denver held signs saying “Stand With Naz.” A hashtag with the same phrase is prolific on Avalanche Twitter.

Mishka Char’s Twitter profile photo is a picture of Kadri, with, “We support Kadri. Stop the hate” circled around it. Char, a Colorado native living in Boston, has posted links to the Hockey Diversity Alliance website in response to the recent slurs directed toward Kadri.

“It’s one thing to say, ‘Oh my God, I hate some player,’ like, I don’t like (Kansas City Chiefs quarterback) Patrick Mahomes because he wins all the time,” said Char, who identifies as biracial. “Or like, I don’t like Tom Brady because he wins all the time. But I would never threaten his family!”

“I hope that, as much as he’s seen these negative comments, he also sees the positive ones; that he sees the ones like, ‘We all stand with Naz.’”

Kadri’s Lebanese background has also earned him some new fans around Denver. Paul Cherabie didn’t know much about Kadri’s career until he came to Colorado. Now, he’s become a hero in the Cherabie household.

“Being a Christian Lebanese American and having a lot of Muslim brothers and sisters, we know where we stand,” Cherabie said. “I couldn’t imagine what he’s going through. He should know that he has fans who stand behind him, and it's not just Lebanese or Middle Eastern, I think a lot of people do.”

Cherabie is a young father who hopes his kids will grow up playing sports “without being hated on.” That’s something Dakkak can relate to. Back at his tint shop, he beams when he talks about his 3-year-old boy and how fast he’s growing. He’s hopeful for his child’s future, one that Kadri is helping pave the way for.

“I want my son to be able to play hockey one day. I want that to be an option,” Dakkak said. “I want his Muslim friends to be interested in that. And I don't want him to be scared away from it because he hears, ‘Oh this sport is mainly for white people.’ I definitely want hockey to be an option for this generation of Muslims.”

Corey H. Jones contributed to this story.