The image is iconic: Two gigantic, jagged peaks come to fine points, covered in slaps of stubborn snow. Below them, a stunning, blue-green lake is surrounded by bald aspens and a carpet of evergreens.

Welcome to the Maroon Bells, the most photographed place in all of Colorado — and one of many beloved natural wonders in the state where visitors are now being limited.

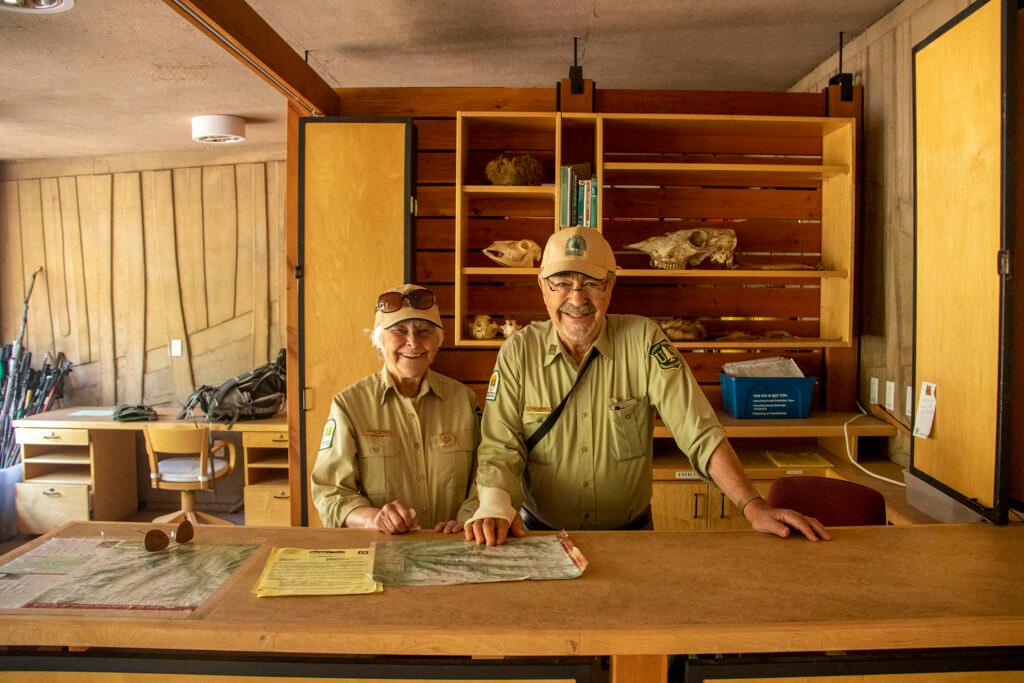

Mike and Margaret Simmons, both in their 80s, believe officials needed to step in to preserve these places. They actually stopped coming for years because it was just too crowded.

“Well look around, you see why people love it,” Mike said, sitting on a bench near a crystal-clear stream. “That's why they come.”

Margaret added: “The claim is they're loving it to death.”

The Basalt couple now volunteer here with the Forest Conservancy. They connect with visitors and walk the trails and are basically extra eyes and ears for park rangers. The couple said things here now are so different than when they first visited in the mid 1960s.

“You could just drive up here and park and go hiking,” Mike explained.

There were no regulations then, not even for camping.

But in the decades since, “everyone discovered it,” Margaret went on. “And they all want to come. And they do.”

More than 300,000 visitors do every year — double the number from just a few years ago. To cope with the popularity, a reservation system has been in place since 2020, capping the number of people who drive in or take the shuttle each day.

For Carbondale resident Nora Serafin, snagging one of those reservations was hard.

“And I try and try and try all day — and finally I do,” she said, with a relieved smile.

The reservation she made for this day was not for her, but for her daughter, Xatziri, there to get her photo taken for her quinceañera, her 15th birthday, in a shoulderless red dress, covered in sparkles and embroidered flowers.

“It's huge. It's big,” the girl said of her dress — not the towering peaks above, showing off her voluminous skirt, falling in a giant circle around her. “It's, like, social distancing!”

She was laughing and beaming but explained that both she and her mom were nervous the new reservation system would make it impossible to take her dream pictures in this beautiful place, in this beautiful dress.

“I'm feeling so happy because this is a place I (was) dreaming about years ago, for this moment,” Nora said.

At the Bells, I met another local woman who tells me she’s made 40 reservations for the season, just to be sure she doesn’t miss out. But there are plenty of others who decided to buck the system entirely and simply bike in, which does not yet require a reservation.

On this day in mid May, opening day, there were actually more bicycles on the road than cars.

But even though it all looked fairly empty, the computer system that holds these reservations said otherwise. Rangers turned away car after car that didn’t have a reservation.

That happened to Leena O’Connell’s family, so they decided to park outside the gate — and walk in. It would have been more than 4 uphill miles, though I was able to give her a ride for the last little bit.

“I was literally counting steps!” O’Connell said, with an exasperated grin once we got to the parking lot.

O’Connell, in her early 50s, was on vacation from Atlanta, only in town for the day. She and her family were determined to see the Maroon Bells no matter what, but she worried this reservation system would make it too difficult for many visitors passing through.

“Since it's new and there are a lot of people who want to come in, I think it could be disappointing a lot of people,” she said.

That’s the kind of story Scott Fitzwilliams hates to hear. He’s the supervisor of the White River National Forest, home to the Maroon Bells and many other well-known spots.

“It’s gonna be hard for that person to leave with that great of an experience,” he said, sitting in this office in Glenwood Springs. “And that's not what we're after.”

Instead, he’s trying to balance access with conservation in the most visited national forest in the country. It attracts more than 14 million people each year — more than Yellowstone and Yosemite and the Grand Canyon combined.

Fitzwilliams explained that the forest is still learning how to best implement restrictions on its most famous spots, including Hanging Lake near Glenwood Springs and Vail Pass Recreation Area. Public feedback is important, as are partnerships with other entities (the Maroon Bells’ shuttle, for example, is made possible with the help of the local transit authority). Fitzwilliams hopes the money from the federal Great American Outdoors Act, which earmarks billions of dollars for projects on public land, will continue to help move all of this forward.

He imagines a day not too far off when people will be able to look up the status of these natural gems online before they arrive.

“I don't think that's getting-to-Mars type of thinking,” he said. “I think that’s right around the corner.”

But for now, many of Colorado’s most visited natural places are going through growing pains as the public and land managers alike get used to the new restrictions. There’s a delicate balance to be struck: In addition to preservation, the future of these lands also depends on people experiencing them, telling others and raising awareness of the need to protect them.

Several hours west of the Maroon Bells, dirt bikes rumbled through a wide-open swath of rolling desert hills known as Rabbit Valley. Just a few miles from the Utah border, it’s wildly popular with off-roaders and RV-ers. For years, they could just show up and park wherever they liked. Starting this season, however, they have to camp in designated spots and fill out a form for a permit. Fees are coming next year.

Zack Kelley, an outdoor recreation planner with the Bureau of Land Management, thinks it’s for the best.

A little more than a decade ago when he was in high school, he used to camp out here pretty frequently, so he bets that some people will see these changes as a bummer.

“But also having a background in natural resources and caring about the multitude of resources here, it’s kind of the best compromise we can make,” he said.

The visitors I talked to generally agree. Kari Prassack, on a car camping trip from Arizona, was happy to see the designated camping sites. For her, it felt good to know that her presence wasn’t harming the very land she came to enjoy.

“Maybe there's something really important around that hill. Maybe there's an owl nesting site or there's some really fragile vegetation,” she said. “And you know that you're not impacting it because you're camping where they're telling you you can camp.”

She had her pick of sites, all with new picnic tables and fire rings. But by the time Ohio resident George Brandt rolled in with his RV, all the quaint, tucked-away spots were taken. So he had to opt for a large, graveled group site, surrounded by other RVs.

“This out here is so wide open, I wish you could use more of it for camping,” he said.

He also understood, though, and worried that without some kind of controls, these special places would be trashed. As a veteran, he said he’d hate to see that happen to his beautiful country.

“There's only one United States of America,” he said. “We need to take care of it properly.”

What that looks like for public land across Colorado and beyond is still very much in process.