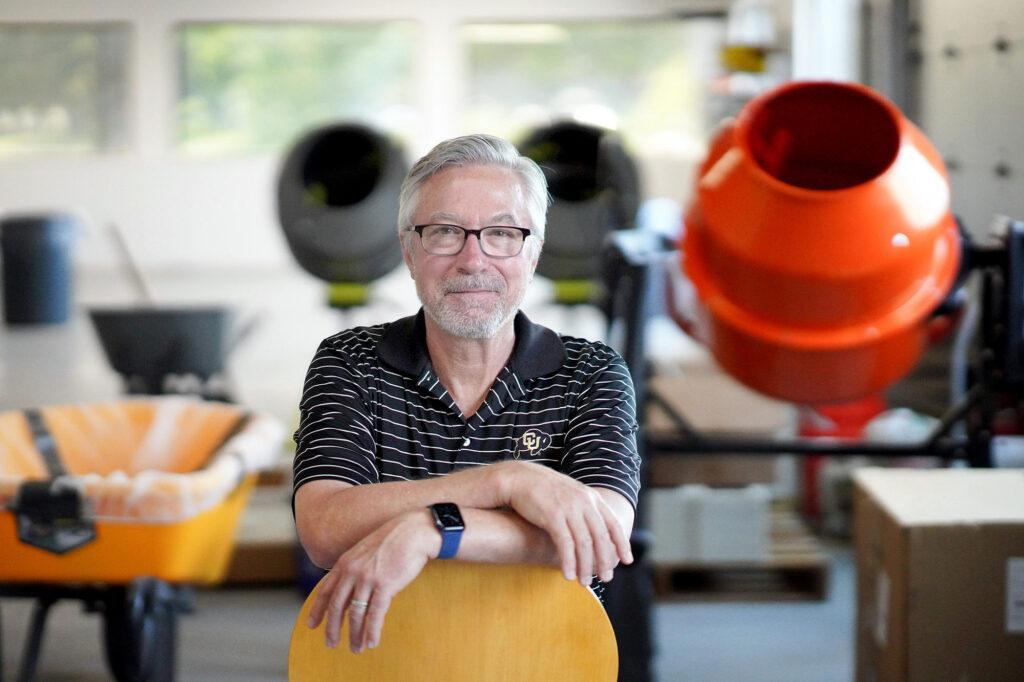

Loren Burnett, the CEO of Prometheus Materials in Longmont, thinks it's time to reconsider the concrete block.

His company's proposed alternative is a "bio-cement" first developed at the University of Colorado Boulder. Inside the Colorado company’s warehouse, sand is loaded in block-shaped molds with micro-algae, which binds the material through the same process corals and oysters use to build their shells. The final masonry units feel like hardened sand castles.

While the process takes energy, Burnett said algae absorbs enough carbon to make the blocks 90 percent less carbon-intensive than traditional concrete.

Through continued manufacturing improvements and different aggregates, Burnett said his company’s bricks could lock away climate-warming gases inside the walls and foundations of future buildings.

"We'll be at zero net carbon soon, and then we have a clear path to get to carbon negative," he said.

The company manufacturing plant is made from the same planet-warming materials it's working to replace. Traditional concrete blocks lacquered in white paint make up the walls. The floor is made of poured concrete. Outside a garage door, concrete sidewalks and driveways bake in 100-degree temperatures.

Concrete is ubiquitous enough to go unnoticed, but there's a good reason to blame the material for some of the staggering heat.

Since the Industrial Revolution, humanity has relied on the same high-temperature process to make Portland cement, the critical glue that binds much of the modern world. It relies on fossil fuel-fired kilns incinerating limestone at close to 1,500 degrees Celsius, which triggers a chemical reaction that releases even more carbon dioxide into the air.

As a result, cement alone accounts for 8 percent of annual climate-warming emissions, a contribution greater than any single county except for the United States and China — a factor that could grow as nations continue to urbanize and add infrastructure.

Cracking into a calcified industry

Those claims of carbon-negative cement have gained early interest from investors.

Prometheus Materials recently announced $8 million in funding led by Sofinnova Partners, a European venture capital firm. Other backers include Microsoft, which hopes the bricks could help it build data centers and meet its corporate climate goals.

The company plans to use the funding to ramp up production of its blocks and other pre-cast materials at the Longmont facility. After that, Burnett said the company plans to create a "just-add-water" mix other companies could use to make concrete in factories or on construction sites.

Unlike traditional cement, the micro-algae has the potential to bind together more aggregates than sand and gravel.

As an example, Burnett showed off a pair of two-inch cubes, one made from crushed glass, the other made from recycled mirrors.

"Imagine a world where instead of using sand, which is a natural resource, you're able to use recycled mirrors and recycled glass," Burnett said. "It becomes very circular."

While those demonstrations might be impressive, they don't guarantee Prometheus Materials can break into the larger concrete industry. Researchers and companies have developed a wide range of greener alternatives, most of which work more like traditional cement and concrete than the so-called “bio-blocks.”

Andrea Schokker, a civil engineer with the American Concrete Institute who leads a new initiative to help builders assess and adopt the new, climate-friendly materials, said the industry is often reluctant to adopt any new techniques — for good reason.

"The less we know about a new material, the more conservative we have to be because we want to drive on safe bridges and have safe infrastructure," Schokker said.

Cost is another concern. Builders use so much concrete each year, Schokker said even a small price increase could put novel materials out of reach for many companies.

Prometheus Materials declined to share details about the cost and performance of its materials. Burnett said the blocks will be more expensive than traditional concrete, but the exact price won't be clear until the company starts making more blocks.

As for the strength and durability of the material, the company claims tests at CU Boulder confirm the product meets or exceeds standards set by the American Society for Testing and Materials, but it won't go through formal trials with the organization until later this year.

Harnessing the power of ancient biology

Wil Srubar, a company advisor and an associate professor of material science and architectural engineering who helped develop the bio-cement in his lab at CU Boulder, is confident the product will work for builders.

"We can make something that meets structural requirements, that's economical, and that can actually be transferred into the commercial space," Srubar said.

The innovations behind the new product began with a grant from the U.S. Department of Defense, which wanted ways to aid construction in remote regions. Srubar and the other scientists found microbes could be coaxed to bind material into rigid structures. As a benefit, those blocks could be broken up and later used to grow another generation of living bricks.

The lab is currently exploring if biology can also help make 3D-printable earth, asphalt and glass. If those ideas succeed, he said builders could someday “actually heal the planet instead of causing more harm to it.”