When Shayla Williams took a teaching job in a little town in Kansas, she was one of three Black educators in the entire district. It was a new experience. She’d grown up in St. Louis after all, and was the first in her family to graduate from high school.

After a few years there, she landed a job in Colorado’s Sheridan school district — in Denver’s metro area — where there also weren’t many Black educators. So later, she was excited to get a job in the much larger Denver Public Schools district, where nearly three-quarters of the students are students of color.

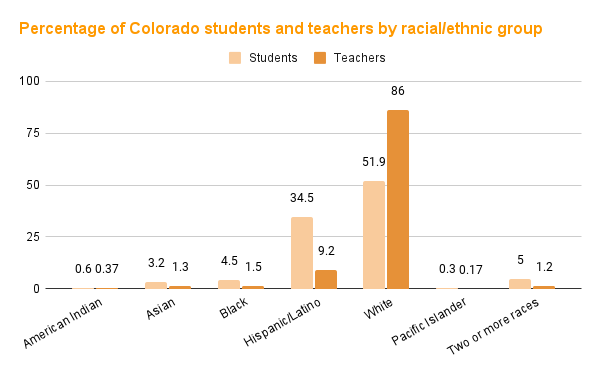

“But then I got here … I’m like, I don’t know they’re as diverse with staff as you would think,” she said. In fact, 75 percent of DPS students are students of color, yet 70 percent of teachers are white. There are far fewer teachers of color in other districts where Williams has worked.

“Every school that I’ve taught at in my 13-year career, I’ve been the only Black teacher, the only Black teacher … and it’s been super frustrating because the kids want to see people that look like them,” she said.

The shortage of teachers of color is a nationwide one, despite years of efforts to reverse the trend. The reasons are complex – sometimes there are financial barriers to getting a degree or Black students choose a major in college that will pay off student loans more quickly. There could be bad experiences in one’s own schooling — or workplace discrimination that forces some out of the profession.

Some burn out from all the extra duties and support they must bring to schools.

“I was made to be the face of the Black community, like ‘Oh, can you help us with our Black excellence plan’ … I was asked to be on extra committees for diversity and equity work … When parents are touring schools and they want to know, ‘Do you have a diverse staff?’ I was the first person whose class they’d pop into.”

Angela Faison, who is the dean of culture at DPS’ West Middle School, recalls trying to recruit people from places like Atlanta or Chicago. When she did, young Black teacher candidates had cultural questions about Colorado.

“There’s things like, ‘Where am I going to get my hair done? Where am I going to go to church? What kind of food do you have?’ … Young women who want to get married, are like, ‘If I go out there, is there going to be a young Black man who's interested in me?’”

In addition, pressures on teachers have been mounting. After one of the hardest school years ever, many predicted a stampede of teachers leaving the profession. The scramble for teachers is intense, with many positions going unfilled for the entire school year. The demand for teachers of color in particular is high.

Shayla Williams and her friend Zuri Hunter survey the room in George Washington High School.

It’s a DPS diversity hiring fair. They notice, however, there aren’t a lot of people of color looking for jobs here.

Both are Black. Both just lost their jobs in DPS’s recent cuts to the central office. Both used to be teachers and now, they’re trying to return to the classroom. Recently, DPS has had a couple of high-profile incidents where educators of color were not asked back. Parents, teachers, and students converged at a May 19 school board meeting, asserting that the district isn’t doing enough to recruit and retain BIPOC teachers.

“For years, BIPOC teachers have been pushed out,” said North High teacher Emely Contreras. “There have been many incidents at my school where teachers of color are being pushed out. I know this first hand.”

DPS maintains having diverse educators is a priority. It’s building partnerships with local and national organizations that represent diverse populations. It’s reaching out to historically Black colleges and universities and Hispanic-Serving institutions. Over the years, it’s experimented with grow-your-own programs, encouraging high school students of color to become teachers.

“DPS is committed to recruiting and retaining a racially diverse workforce that is representative of the students we serve,” the district said in a statement. “We are intentional in our efforts to recruit educators who identify as BIPOC.”

The district has a larger proportion of teachers of color than any district in Colorado. DPS, which has about 4,700 teachers, actually grew its ranks of educators of color over the course of the last school year by 259 teachers.

A growing body of research shows educators of color can help close achievement gaps in a number of areas: test scores, discipline rates, high school graduation rates, and access to advanced coursework. Black students who’d had just one Black teacher by third grade were 13 percent more likely to enroll in college — and those who’d had two were 32 percent more likely, according to another study.

Shayla Williams still remembers the three Black teachers she had from preschool through college.

“And I can remember how they made me feel, it was nice to go to school every day and see that my teacher looked like me,” she said.

Even when she visited schools as a technology support person, Black students would run up to her in excitement:

“They just instantly relate, they make that connection of ‘I see you, you see me’ and they feel seen,” she said.

Her friend Zuri Hunter said it’s more than sharing the same skin color, it’s sharing a lived experience.

“It says something when you come from an underprivileged, marginalized group and you understand the students that you teach, because you personally go through that, so you’re invested in their learning, you’re invested in their academic success,” Hunter said.

The two friends have applied to a few places, but as former elementary school teachers, it’s been tougher than they thought.

The mass exodus of teachers some thought was going to happen hasn’t so far come to pass.

Early numbers from a couple of Metro districts show solid retention rates. Cherry Creek had a 90 percent retention rate. Aurora had an 88 percent retention rate. The retention for teachers of color in those districts was slightly higher. Denver Public Schools won’t release retention rates until the end of July, but it’s hired back almost all of the teachers it lost — it began the year with roughly 4,700 educators, and has the same number now.

Jefferson County has about 90 percent white teachers, and 10 percent educators of color. The district said it doesn’t calculate attrition numbers until school starts in August as some teachers leave or retire in the middle of the summer. The district said it had only 19 general teacher positions open as of June 15, but 71 total positions were vacant, including special education teachers, social workers and school psychologists.

“Is (the teacher shortage) definitely worse today than it was three years ago? Yes, but it didn’t come to fruition in the way people thought,” said Colleen O’Neil, associate commissioner of educator talent for the Colorado Department of Education. She said when there’s high inflation that contributes to economic instability, people tend not to leave stable positions.

“Education and being a teacher are some of the most stable positions we have,” she said.

O’Neil said some educators reported in teacher “exit” and “stay” interviews that they’re staying because the issues teachers are facing have been elevated.

“Districts are responding to say, ‘We hear you, we hear that you’re tired, we hear that you’re overwhelmed, we hear that we can do more to help you stay in this position,” including reducing initiatives like large-scale curriculum changes over the summer, she said.

The numbers of teachers of color statewide, however, has been increasing incrementally over the past five years, including at teacher preparation programs.

Shortages, O’Neil said, have been around for decades. She recalls a 1972 article talking about shortages in early childhood, special education, and math educators – the same shortages that exist today. Statewide, there’s been a 6 percent increase in teaching positions that remain unfilled during the school year since 2019-2020, and an increase in teachers leaving suddenly during the year, usually due to an emergency like a child care or family crisis.

But the fact remains, there just aren’t enough people of color who want – or can afford — to be teachers.

So some districts are turning to white candidates who may be more willing to educate themselves and work on race issues.

Teacher candidate Jonathan Miller, armed with resumes, sits at the table of the Robert F. Smith STEAM Academy, a new school in northeast Denver that focuses on Black history and culture. Miller has a keen interest in equity and culturally responsive teaching and has taught English in refugee camps abroad. But he knows he may not be exactly what the school is looking for.

“How would I as a white male fit into the culture?” he asked Assistant Principal Benicia Mitchell. She tells him everyone is welcome at the school, but the school does center on the Black experience and amplifying the voices that have been erased in history.

Mitchell said she’s noticed fewer Black applicants for secondary school positions.

“It’s a struggle, it’s almost like looking for a needle in a haystack … and I’m thinking of even traveling to other states where there are more Black educators and marketing differently toward them.” For example, selling that the school is an “innovation” school, which means there is a lot more flexibility in planning, collaborating and assessing, she said.

Miller has a barrier to getting hired; he doesn’t have a teacher’s license. But he’s worked in before- and after-school programs, taught English in refugee camps abroad, overhauled a library and built a school maker space.

“It was very important to me that when students walked into the library, they saw their faces reflected in the books that they were checking out,” he said. Checkouts went through the roof, he said.

He also worked extensively with youth in residential treatment programs.

“My conflict management and behavior management skills are really well-refined … That’s something I’m passionate about and I care a lot about,” he tells Angela Faison, dean of culture at West Middle School. She tells him that teaching social and emotional skills is a huge part of what teachers do, alongside academics.

Miller tells her he’s on the same page. “You have to get the kids in a position where they’ll be able to learn. You can’t learn where you’re fighting 50 other battles. I fight for equity initiatives in everything I do.”

Schools are desperate for those skills. And Miller is about to enroll in an alternative licensure program at Metro State University Denver. That means if he can find a school to hire him – he’ll continue taking a night class once a week in the two-year program until he has his license. For now, he’s up against licensed teachers in competition for a job. And — Jose Piza of the Denver Green School says he’s seen an uptick in teacher candidates from other states. He just hired one from Florida.

“Everything that’s going on in Florida, she’s like, ‘I’m just done,’ and she’s leaving,” he said.

The recent wave of anti-LGBTQ legislation there, as well as mandates to avoid topics of social justice and even social and emotional learning, is causing many teachers to rethink the profession.

Across the state, hiring directors will continue the mad scramble for teachers all summer long.

Meanwhile, former teacher and regional technology specialist Zuri Hunter landed a leadership post at a Denver elementary school.

“I love that their teacher population is diverse like the students that they serve,” she said.

Jonathan Miller is thrilled to report he’ll be teaching language arts at a middle school in west Denver next year, one of the ones he connected with at the job fair.

Miller must first pass the Praxis teaching exam this week.

Shayla Williams was offered a job on the spot at the hiring fair. The school, almost all Black and Hispanic, was upfront – it was desperate for a single Black teacher. She toured the school.

“When the kids saw me, they were like, ‘Are you going to be a teacher here? I love your hair,’ like ooh, “Who are you, who are you?’ The principal warned me, she said when they see you because they are not used to seeing African American teachers in this building, she was like, ‘They’re going to want to talk to you,’ and that is exactly what happened.”

It was inspiring, but also disheartening.

“That is why we need to encourage other African American teachers, people of color, to become teachers, because kids want to see people who look like them.”

For a variety of personal and other reasons, the school wasn’t the right fit. Williams instead decided to take a job with a curriculum company supporting schools.