Remembering Waldo Canyon fire | A fire expert reflects on wildfire history | Waldo was a catalyst for mitigation | Lessons learned by Colorado Springs

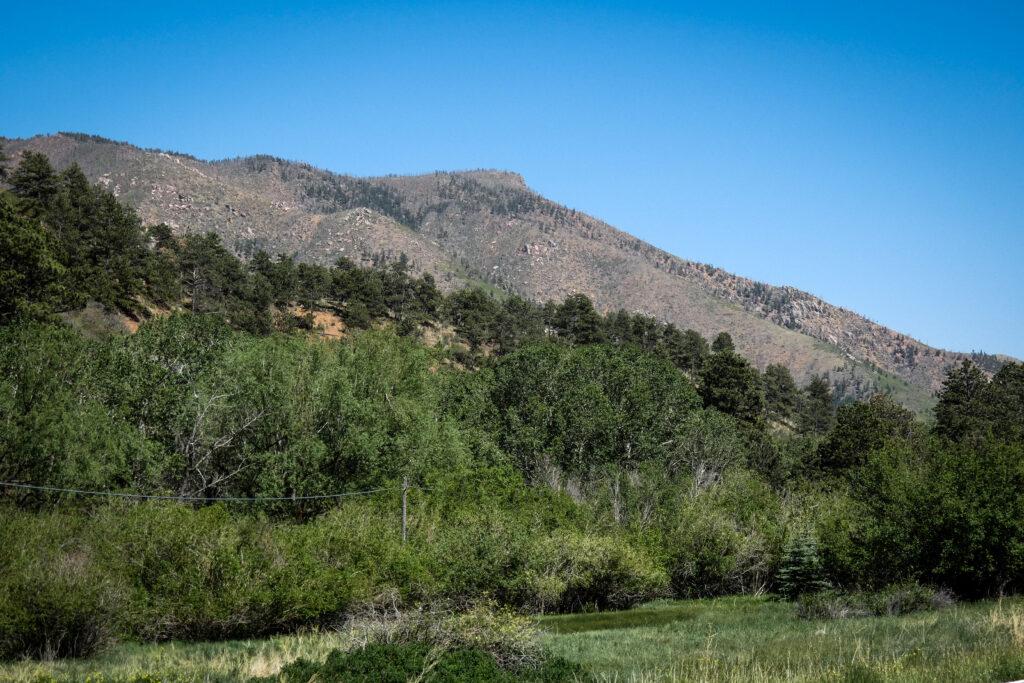

The town of Green Mountain Falls is surrounded almost entirely by the Pike National Forest. It sits directly south of Highway 24 from the Waldo burn scar. Ten years ago, the town was evacuated for eight days while the fire ravaged the opposite hillside. Officials say the fire very easily could have destroyed the town, had the weather driven it that way.

An analysis by the USDA and the U.S. Forest Service placed Green Mountain Falls in the 99th percentile when it comes to wildfire risk and consequence. That means it's not a matter of if, but when the town will see devastation of its own.

Jesse Stroope, facilities manager for the Green Mountain Falls Foundation, said the Waldo Canyon fire was a wake-up call.

"You don't sleep, you don't rest, you don't eat when you're evacuated, because you're worried about your life here in Green Mountain Falls," he said. "We had written an evacuation plan, but it could have been stronger and it's definitely stronger today as a result."

Mitigation efforts are also stronger after the Waldo Canyon Fire. The foundation owns more than 200 acres surrounding Green Mountain Falls. That includes the 98-acre H.B. Wallace Reserve just a little ways southeast of town. Stroope said this area was a critical starting point in the journey toward improving fire protection and around the town.

"I don't think that we knew what we were starting at the time. But it was the first major piece to be mitigated around town," he said.

They've removed low limbs and thinned ground vegetation. Sun shines through a thriving grove of aspens and squirrels clatter up and down a bare pine trunk, intentionally left during the mitigation as a home for wildlife.

David Douglas is the chairman of the Green Mountain Falls Fire Mitigation Advisory Committee. He said the reserve serves as an example for the 749 year-round residents, showing that mitigation doesn't mean demolition.

"I think one of the big issues that we're tackling right now as a committee is education because people are afraid of losing their forest," he said. "...and it sounds odd. It's contradictory because they're afraid of losing their forest to fire, but they're afraid of losing the forest as it exists and the beauty of it that they appreciate so much."

The group is looking to teach home and landowners how to prevent fire on their property — things like cleaning up wood piles and reducing underbrush. If that happens, and the mitigation on land owned by the city foundation continues too, the town would have a perimeter of defense against a fire.

But depending on where a fire starts and considering they're burning hotter and fiercer than ever because of climate change, it still might not be enough.

"The consensus is, in Green Mountain Falls, very little can be saved if we have a canopy fire," Douglas said.

"I think what we're beginning to see is people realize we have to do something," he said. "Ultimately, it doesn't seem like, when you look at the overall scheme of things, that what little bit I'm gonna do on my properties will make a difference. It makes a huge difference."

The town has partnered with Colorado Springs Utilities, the U.S. Forest Service and the Coalition for the Upper South Platte (CUSP) to get federal mitigation funding. One such program pays 60 percent of the home mitigation cost for residents. Green Mountain Falls is technically in a wildland urban interface, or WUI; That's any area where human development meets nature.

The town has considered adopting a WUI code for buildings, but it poses a large expense for homeowners.

"...because all of a sudden you're looking at things like replacing decks with non-flammable materials, replacing roofs with non-flammable materials, siding with non-flammable materials," Douglas said."So that's probably a little bit down the road because we need to really consider that in terms of the financial issues that homeowners have."

The conversation and the education about fire prevention in Green Mountain Falls are both ongoing and evolving. But Jesse Stroope says the drive to save this beautiful hamlet, tucked away against the mountain, is here to stay.

"This is our town. I think there's spirited people that live in Green Mountain Falls and we want to fight for our town," he said.

Due to limitations posed by the canyon paired with high costs and the intensity of manual labor, only about 10 percent of the land owned by the Green Mountain Falls foundation has been mitigated thus far, with a focus on the areas at the highest risk for fire.