Don Cameron, a former science teacher and current city councilperson in Golden, Colo., has remodeled his house into a living example of the "electrify everything" movement.

The brick ranch home was fit for the cover of a green living magazine even before the remodels. A thriving community garden takes up one side of the front yard, where Cameron and his neighbors grow vegetables. Terraced beds on the opposite side of his driveway support a riot of wildflowers.

Over the last few years, Cameron has turned his attention to the home's climate impact, working to eliminate any system using fossil fuels. His natural gas furnace, water heater and stove are now gone, replaced by electrical appliances. The shift means a rooftop solar array now covers his home energy use.

Cameron said the retrofit wasn't cheap, but he hopes his home becomes an early example for others.

"I don't think people should do this for a return on investment when it comes to money. It's a return on investment when it comes to the environment," Cameron said.

Scientists have called plans to transition households to electricity “a linchpin solution" to combat climate change. By eliminating natural gas stoves and furnaces, homeowners can remove a potent source of greenhouse gases and indoor air pollution. Electric alternatives — like heat pumps and inductions stoves — can take full advantage of an energy grid increasingly powered by solar and wind power.

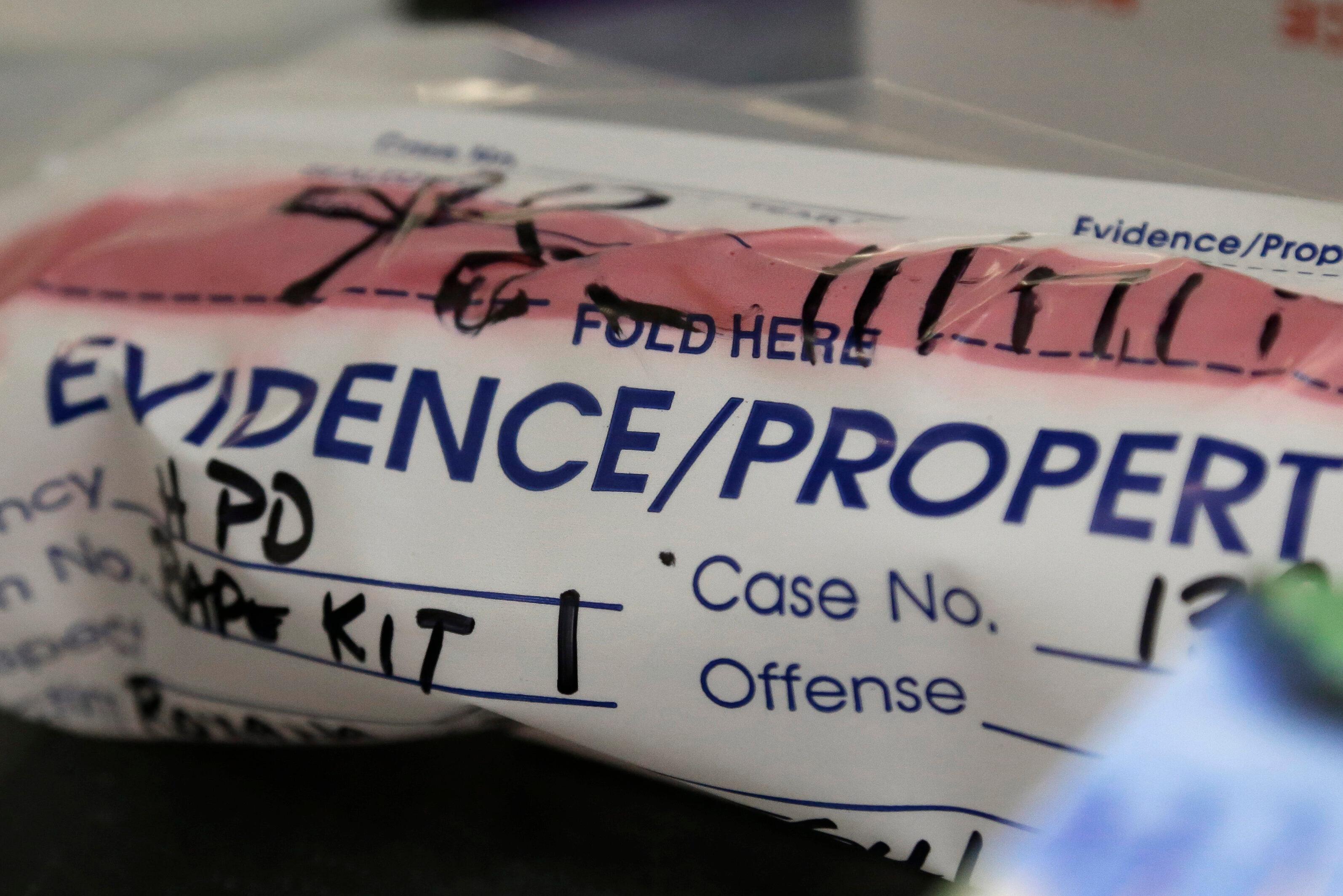

The culmination of Cameron's project worries some experts. After eliminating any need for fossil fuels in his home, he asked Xcel Energy to cut him off from its gas system entirely. All that remains of the link is a pair of capped metal stubs on an exterior corner of the house. Removing the gas meter excused Cameron from a $15 monthly service fee all customers pay to help maintain the extensive network of pipelines operated by Colorado’s largest utility.

Why ditching gas could leave behind higher bills

A recent paper scheduled for publication in the “Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists” explores what could happen if wealthy homeowners lead an exodus from U.S. natural gas utilities.

Without proper planning, the research suggests a rapid energy transition could leave lower-income customers with higher gas bills, raising questions about the economic fairness of shifting homes away from fossil fuels.

"The tricky thing with electrification is that the utility still has to pay for the existing gas network and the maintenance on it, even as they're losing customers," said Catherine Hausman, an associate professor of public policy at the University of Michigan and a lead author of the study.

Hausman doesn't see evidence of a rush away from the natural gas system. Federal data show the U.S. added more than a million natural gas customers between 2019 and 2020. Rapidly growing states driving the growth include Colorado, which added about 27,000 natural gas customers over the same period.

Hausman said it's worth studying the dynamic because many plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions call for the rapid electrification of buildings.

For example, the United Nation's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which compiles recommendations from the world's top climate scientists, lists the strategy as critical to meeting international climate targets. Meanwhile, Colorado's climate roadmap also calls for policies to boost the market for electric heating and cooling systems.

To measure the potential effect of a speculative problem, the study authors looked at parts of the country like Birmingham, Ala., which has bled natural gas customers due to population loss.

As customers left the system, Hausman said utilities spend the same amount on ongoing costs, like preventing leaks, serving customers and paying the debt on existing systems. Those costs are then paid by a shrinking number of customers who pay higher prices. On average, the research found that a 40 percent drop in a natural gas network’s customer base corresponded with an annual bill increase of $115.

The American Gas Association, a trade association for natural gas utilities, has raised similar equity concerns when advocating against policies restricting natural gas in new buildings. Hausman stressed she doesn't see her conclusions as a reason not to ditch the fuel.

"This does not mean electrification is a bad idea. It means we need to be careful with how we transition to that goal," Hausman said.

Ideas for a more equitable transition

As the electrification movement gains momentum, environmental groups and utility customer advocates have proposed policies to assist lower-income residents and help them join a shift away from fossil fuels.

One plan could be to shift entire neighborhoods away from natural gas. Sherri Billimoria, a manager with the environmental think tank RMI, formerly known as the Rocky Mountain Institute, compares the idea to "pruning" the branches of the natural gas system. She said that utility companies could target disadvantaged communities first, removing an entire section of an aging natural gas system and potentially reducing maintenance costs.

Northeastern states with aging natural gas infrastructure are already testing the idea. Massachusetts has approved several pilot projects to electrify residential areas with geothermal heat pumps. A similar plan is now under consideration in Philadelphia.

Billimoria said another prescription could be capping energy costs based on household income. While ideas aren't in short supply, she said an initial step should be to stop natural gas utilities from continuing to add customers and expand their networks.

"All of those new investments are just adding to what will need to get paid off in the coming decades," Billimoria said.

Some coastal communities, like Berkley, Calif., and New York City, have approved ordinances to ban natural gas in all new construction. At the same time, many red states have passed bills to preempt local communities from passing similar restrictions on natural gas.

Colorado has settled on a more subtle and less controversial approach. Leaders in Denver and Boulder are nudging developers toward all-electric designs with incentives and building codes. On the state level, lawmakers approved a bill requiring gas utilities to cut emissions by 4 percent by 2025 and 22 percent by 2030. The law offers companies a menu of strategies to hit the targets including electrification.

Xcel Energy must submit its climate plan to the Public Utilities Commission by Aug. 1, 2023. All other gas companies have until Jan. 1, 2024.

State Sen. Chris Hansen, D-Denver, who sponsored the bill, said he expects state utility commissioners will consider bill impacts, specifically around so-called "stranded assets" like unprofitable natural gas networks. He said complex financial instruments like securitization could blunt any impact on low-income customers.

"The good news is we have tools in place that would allow the PUC to allow the transition in an equitable way and make sure certain ratepayers aren't getting disproportionate costs," Hansen said.