Upbeat tunes played at Beauty Supply Warehouse in Aurora as Leeanda Robinson Bragg washed one customer’s hair, while she greeted others.

“Hey kiddos!” she says, as a mother and her kids strolled in. “How you guys doing?!”

A sign at the entrance read “Get a CUT & Blood Pressure CHECK.” Sitting at a pair of card tables inside was a group of volunteers with the nonprofit Colorado Black Health Collaborative.

“Have you had your blood pressure checked recently?” asked one volunteer, as she attached the cuff to the arm of 30-year-old Adrian Elias, a customer from Aurora.

Why is he getting his blood pressure checked?

“Because the opportunity was here,” he said. “I'm actually here to get a haircut.”

Elias used to be a truck driver. Now he’s a warehouse manager. He decided not to get vaccinated for COVID-19. But he’s made other changes and lowered his blood pressure.

“I started losing a lot of weight. I was almost 400 pounds and now I'm about 349. So, been putting in a lot of work,” he said. That included changing his diet, less soda, less bread, “just eating better.”

His son, also named Adrian, gave a big grin and enthusiastic thumbs up when asked if he was getting his blood pressure checked too.

Colorado Black Health Collaborative hosts the barbershop and salon screenings every week.

Longtime Denver internist and primary care Dr. Terri Richardson smiled at the exchange.

She helped found the Colorado Black Health Collaborative. It’s a community-based organization committed to improving health and wellness in the state’s Black, African, and African American communities. It works through collaborations and partnerships with community-based organizations, nonprofits, public organizations, private entities and government agencies.

Every Saturday since 2012, volunteers have been giving health screenings at salons or barbershops. The pandemic forced the program to take a two-year break, but Richardson said it’s back.

“We kind of re-rolled out the program in June.”

She said Black communities have among the highest rates of high blood pressure, or hypertension. She described it as “a silent killer,” increasing risk of a long list of problems like stroke and heart failure.

“It's damaging your vessels. It's affecting your heart over time and you can end up with a lot of problems,” Richardson said.

High blood pressure is a treatable disease through diet, exercise and medication. But it needs to be detected first.

Blood pressure screenings are an entry point, she said, they open the door for more conversations about health.

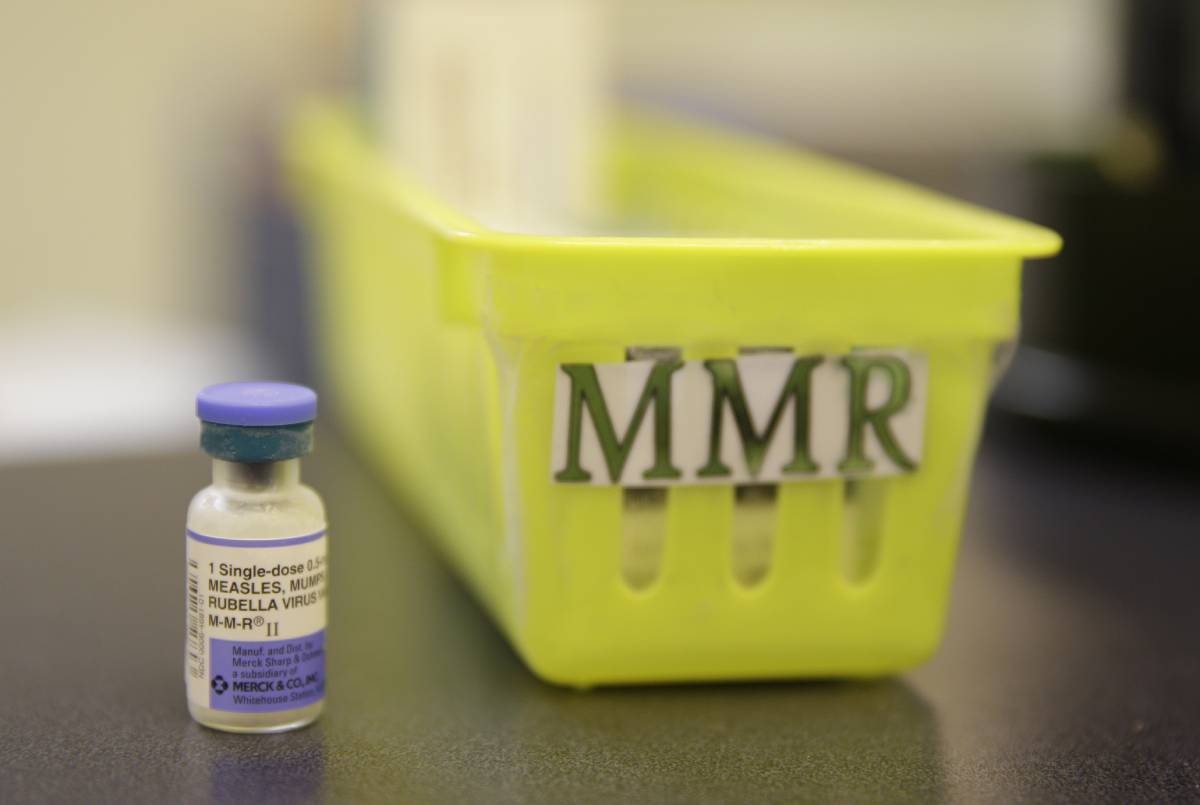

Volunteers here also offered educational materials, information about COVID-19 vaccines and referral advice. But Richardson said it’s a soft sell.

“We talk about lifestyle issues, but some people need medications in addition to that, and we're not trying to be their doctors, but we do wanna get them connected,” said Richardson, who retired last year after a 34-year medical career serving some of the state’s most diverse populations, most recently with Kaiser Permanente.

Since its inception a decade ago, the program has screened more than 9,000 people for high blood pressure. Volunteers have also distributed medical literature, pamphlets, and health-oriented giveaways like hand sanitizers, masks, test kits, pedometers and fidget spinners for stress.

“It is really fantastic that there are both people looking specifically to reach members of the Black community in Colorado and that they are specifically working to reach people in places where they are,” said Dr. Tamaan Osborne-Roberts, a family physician and the first person of color elected as president of the Colorado Medical Society. He is not involved in the program. “I think there's a lot to be said for that.”

In a business that gets a lot of foot traffic, hosting health screenings just makes sense, said salon owner Leeanda Robinson Bragg.

“Stylists and barbers, we're everything, nurses, doctors, you know, psychologists, everything. So we hear it all,” she said. “And it's just good to have them here to make us aware. Awareness is everything.”

She said the last two years have raised awareness about all kinds of health issues.

“With the mental health, I think it's just now that people are feeling more comfortable to talk about it,” said Robinson Bragg.

Hosting the volunteers at salons and barbershops helps build trust in a community that's been neglected and abused.

As she spoke, Robinson Bragg combed and cut the locks of Sha’Kai Swing, who nodded her head and said it all comes down to trust.

“Hair is a very important thing, and I myself don't let anyone else touch my hair,” she said.

Swing, who works in HR, said historically Black Americans have a suspicion or distrust of medical providers. But health volunteers coming to her stylist’s salon helps ease that.

“So I think it's a really great thing that they're in these spaces and assisting the people in these communities that are so often left behind.”

One recent poll found nearly six in 10 African Americans express complete or partial distrust in the nation’s health care system. Another showed that’s exacerbated by a lack of Black health providers and negative interactions with the system.

Richardson said “that really is a reason why we're here, because we're trusted partners and we've gotten to know these people and we just feel like they're part of the family. They feel like we are part of their family and that just makes a program what it is really.”

And this kind of program is perhaps more critical than ever.

Recent data show life expectancy for all Coloradans has dropped sharply since the pandemic began, with Black and Hispanic Coloradans not living as long as white residents.

Another customer, 18-year-old Camry Prince, a receptionist, said she’d caught COVID-19 three times and is now fully vaccinated. She’s immunocompromised and said the pandemic taught people a lot about self-care.

“So we had to learn how to grow and how to take care of ourselves from the comfort, our own home and within our community,” said Prince.

The program is now working with 14 Black barbershops and salons in Denver and Aurora, taking health screenings directly to the community, meeting people where they are.

Dr. Tamaan Osborne-Roberts said he thinks it’s a promising example that deserves further community investment.

“I think we need more. And I think we need to see these sorts of efforts mainstreamed. Reaching a given community shouldn't be a revolutionary act. It should be something that government and private business seeks to do as a matter of course,” said Osborne-Roberts, who practices at Iora Health on South Federal in Denver. “I think this is a great model.”