U.S. farmers started shipping fresh potatoes into the Mexican interior in May, about 20 years after an initial deal was signed between the two countries.

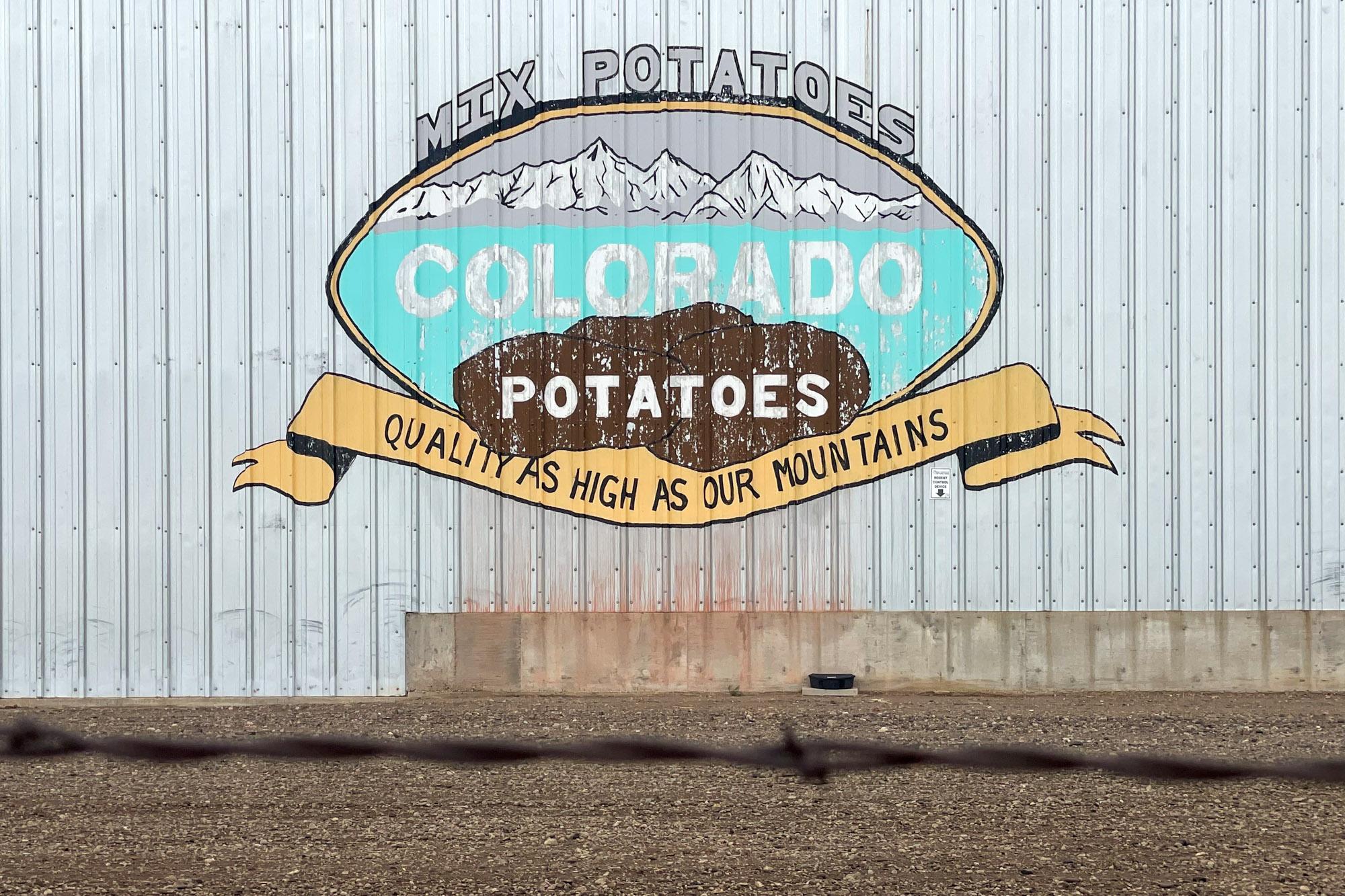

For the San Luis Valley — the second-largest potato-growing region in the country — the Mexican market could bring in millions of new customers, but farmers there aren't sure the deal will last, according to Jim Ehrlich, the executive director of the Colorado Potato Administrative Committee in Monte Vista.

“We’re really skeptical that Mexico will not find a reason to shut the market down again,” he said.

Barriers to the Mexican potato market appeared to come down after the Mexican Supreme Court ruled last year to allow fresh U.S. potatoes to be sold throughout much of the country. Previously, U.S. farmers could only sell their crop in a 26-kilometer-wide zone, which is about 16 miles, just over the southern border.

The deal 20 years ago was staggered to initially allow sales just within that 26-kilometer zone. After a few years, potatoes should have been sold throughout the entire country. Ehrlich says a powerful group of Mexican potato farmers have helped block potato shipments from expanding beyond the first tier of the agreement.

“We were stuck with the 26 kilometers (limit) from 2003 until just recently,” he said.

The first potato shipments made it beyond the 26-kilometer boundary about two months ago, and Ehrlich said he has heard reports of around 120 shipments going through without any issues.

Industry organizations supporting the U.S. potato industry estimate that access to the entire Mexican market could grow the total export value of fresh potatoes by $190 million a year. The U.S. currently exports about $60 million of fresh potatoes to Mexico each year, according to the National Potato Council.

Even though the market in Mexico could be a boon to farmers in the San Luis Valley, who enjoy an advantage over growers in Idaho due to their proximity to the border, Ehrlich says farmers aren’t scrambling to plant new rows just yet.

For one, he’s skeptical that the deal will hold, especially after 20 years of uncertainty.

“Once the new harvest comes in September and we can actually ship larger volumes, we anticipate they are going to come up with some kind of roadblock,” he said.

Potato farmers in Mexico have held off American competition through the courts for the better part of two decades, and Ehrlich says he can’t fault them for trying to protect their isolated market.

A short water supply in the San Luis Valley is yet another challenge for farmers, even if the Mexican market is to open up fully.

Much of the valley is currently in drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

“We’re short of water here,” said Ehrlich, “I think it’s feasible we could plant more, but not a whole lot right away.”

The San Luis Valley currently plants about 50,000 acres of potatoes, down from 73,000 when Ehrlich moved to the valley 26 years ago. Even with a market to the south that could grow by hundreds of millions of dollars, Ehrlich doesn’t expect to see dramatic changes to the valley just yet.

“If the market stays open all through the 2022 crop season, and in May of 2023 if things look good, then yeah there might be some more planted,” he said. “It's questionable, but maybe.”

It’ll take more than a few months of successful shipments to convince San Luis Valley farmers to start planting more potatoes, according to Ehrlich. But, he says, if the deal proves stable, Colorado spuds could increasingly make their way south of the border.