Local governments in the northern Front Range are pushing back against oil industry leaders and Weld County officials who claim that emissions of a potent greenhouse gas are falling even as drilling in the region has grown.

Environmental experts disputed the industry claims at a meeting of the state’s Air Quality Control Commission on Thursday, citing data collected over several years that show methane emissions have not fallen – and that oil and gas wells are still responsible for much of them.

Cindy Copeland, the air and climate policy advisor for Boulder County, told commissioners that “local sources of methane are fueling the climate crisis.”

“Despite newer regulations, oil and gas emissions have not decreased,” Copeland said. “Individual source emissions may have decreased, but production has continued to increase, which is a key point here.”

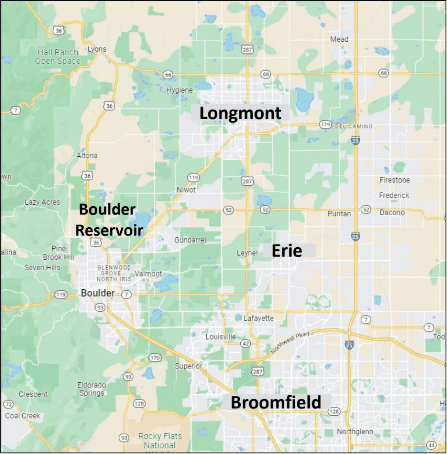

Copeland presented with environmental officials from Broomfield, Longmont and the town of Erie. She said their presentation was a direct rebuttal to data that Weld County and the Colorado Oil and Gas Association presented to the state’s air quality regulators in May.

“We felt like we needed to respond to that,” she said in an interview.

The officials said their air quality data, which was collected at more than two dozen monitoring stations and goes back to 2017, was more precise than the data used by Weld County and the state’s fossil fuel advocates.

Their findings showed releases of methane — a greenhouse gas that traps heat with 25 times more potency than carbon dioxide — have not declined in recent years. In Longmont, methane emissions are rising faster than the global average and are higher in the section of the city closest to oil and gas wells.

Oil and gas emissions, they said, are also largely responsible for volatile organic compounds that form ground-level ozone, which irritates lungs and is linked to health problems such as asthma, lower birth weights and premature deaths. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency designated the northern Front Range as a “severe” violator of federal ozone standards in April, scolding the region for failing to bring levels under control.

“What we found was surprising and concerning,” said Jane Turner, Longmont’s oil, gas and air quality program manager, adding that Longmont has no active oil and gas wells.

On the contrary, Erie is surrounded by hundreds of wells, some of which have continued to leak methane despite being plugged, said David Frank, the town’s energy and environmental program specialist.

Broomfield also studied health issues of residents who live near oil and gas wells. Adults who lived closer to wells reported more upper respiratory symptoms, such as nosebleeds, nausea and shortness of breath, than those who lived further away. Children reported more lower respiratory and gastrointestinal issues.

Officials also tracked how wind carried volatile organic compounds from specific wells and leaks into their communities.

In a statement, Colorado Oil and Gas Association President Dan Haley accused “politicians in Boulder and the Boulder suburbs” of cherry-picking data to stop oil and gas production in the state.

His group and Weld County relied on data collected from a NASA satellite and a state-run monitoring station in Platteville, a town 9 miles north of Fort Lupton. Their presentation to the Air Quality Control Commission concluded that methane emissions in the northern Front Range had fallen by more than half from 2013 to 2019, a period during which fossil fuel production more than tripled, according to Weld County data.

But the local environmental officials cautioned that those sources were not accurate indicators of greenhouse gas emissions and volatile organic compounds. The satellite collected data once a day and did not report surface-level data; the Platteville station only recorded data once every six days during the morning hours, when levels are typically lower.

“Platteville is not the oil and gas hotspot that it once was,” said Turner, Longmont’s air quality program manager. “It’s not where most new oil and gas development is occurring, and this may be part of why we see the levels decreasing there.”

Rising ozone and poor air quality are damaging the health of people in the region, the officials said, urging the Air Quality Control Commission to use the local data when enacting policy around oil and gas production.

“The more monitors you have in an area, the better chance you’re going to have of getting a clear picture of what’s going on,” Turner said.