Republican Holly Anderson and Democrat Sherry Meier don’t agree on much politically — Anderson was looking forward to voting for Congresswoman Lauren Boebert, Meier was ready to vote against her.

But neither of them will get that chance; their homes in Custer County are no longer part of Boebert’s district. And that’s led to a discontent that both women share.

“It doesn't make any sense. I don't get it. I don't like it. I don't like what's happening,” said Meier.

Thanks to redistricting, they’re now in the 7th congressional district, which stretches from rural mountain counties like Custer and Chaffee all the way up to the Denver metro area.

“Jefferson County is definitely not rural. That's influenced by city thinking and the rest of [the district] is very rural,” said Anderson, looking at the map of her district.

Before its boundaries were redrawn, Colorado’s 7th congressional district was focused solely on the western and northern suburbs of Denver. But as the state’s independent redistricting commission shifted lines around, it shed urban communities and stretched out into some of the central mountain counties of Colorado.

That’s turned it into the poster child of something people mentioned a lot during the redistricting process: the rural-urban divide.

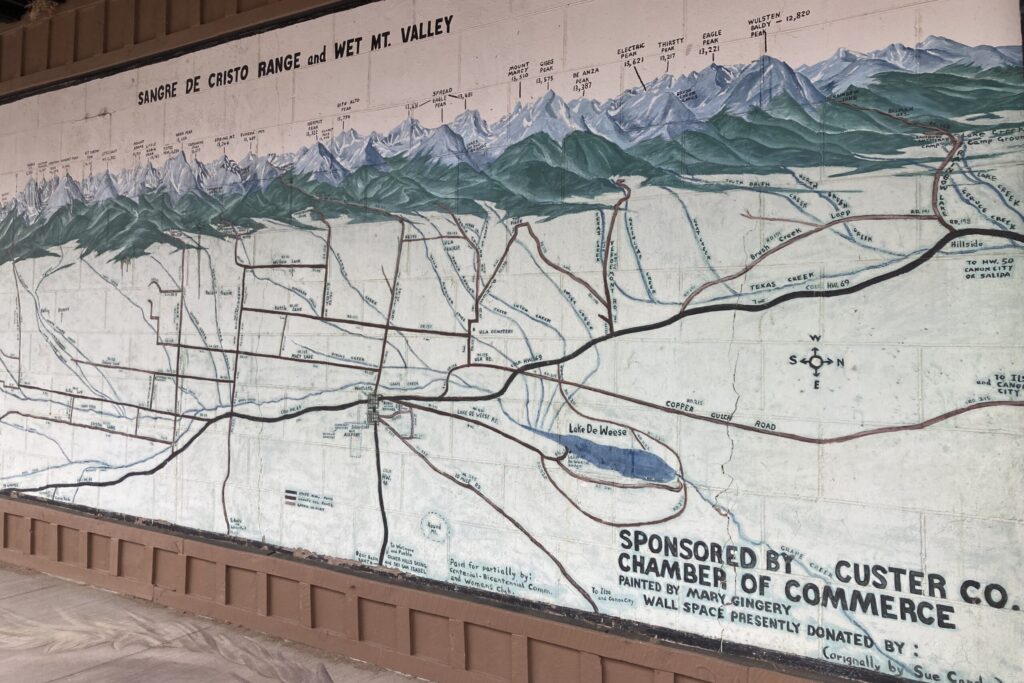

Custer County, which lies southwest of Pueblo and is perhaps best known for being an international Dark Skies Community, has just under 5,000 people. Unaffiliated voter Jen Taylor describes the area as “more animals than people.”

It’s not necessarily rural vs. urban thinking or values or even politics that’s her main concern. It’s the sheer numbers.

“The higher population of people who live in cities, as opposed to the lower population in the rural areas,” she said, “tends to overwhelm the ideas and needs of the rural area.”

Just two counties in the district — Jefferson and Broomfield — make up 82 percent of its population.

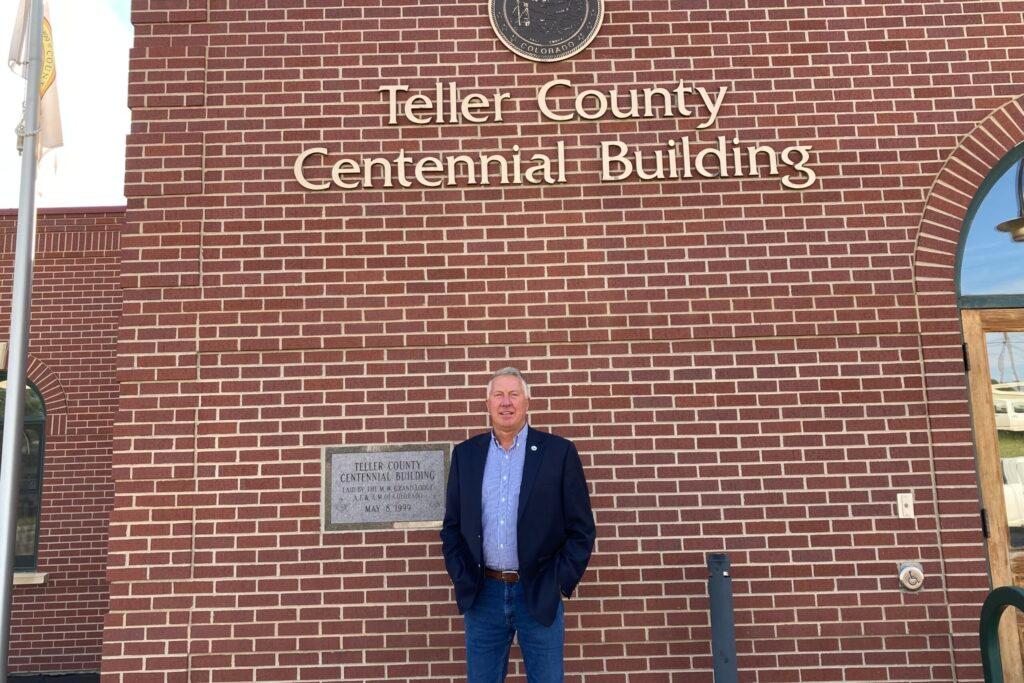

“The first time I saw that map and being included with Jefferson County, there was some disappointment,” said Fremont County Commissioner Kevin Grantham.

The Republican says he knew the county would get moved out of the fifth district, which it shared with Colorado Springs for the past decade. But he thought Fremont would get included in either the Western Slope or Eastern Plains congressional districts, in acknowledgment of its rural character.

That said, he wasn’t particularly surprised or shocked by the outcome — because it’s about redistricting math. The state has to ensure each district has the same amount of people, when people aren’t evenly distributed across the state.

“We knew that we were going to be stuck with an urban area — and to be perfectly honest — even a conservative urban area like El Paso and Colorado Springs has different priorities (from) rural, less populated areas,” he said.

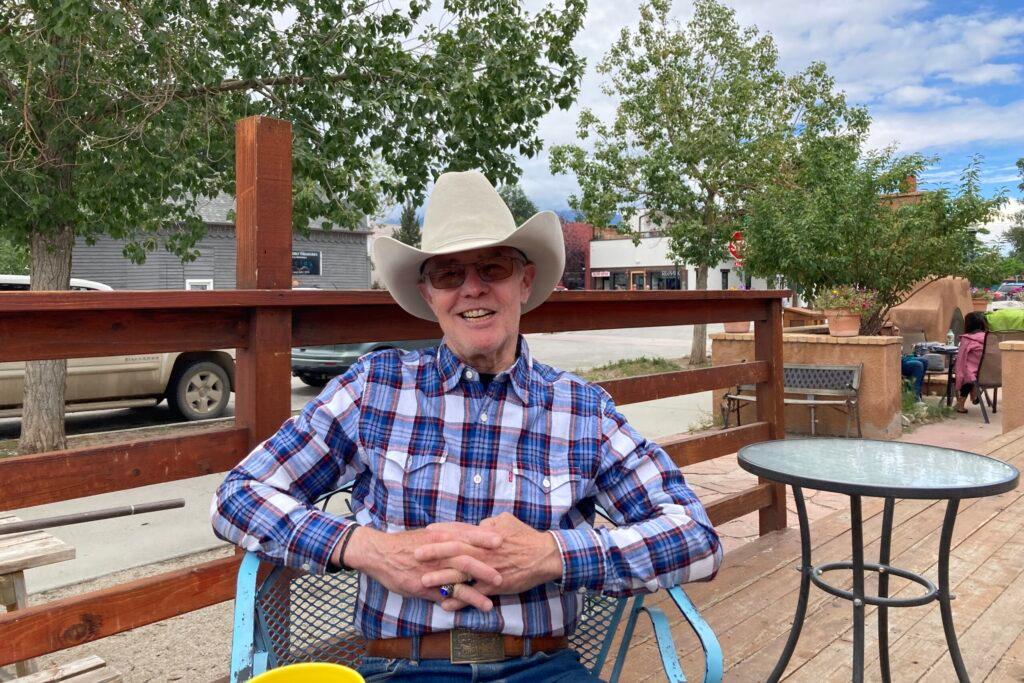

Jordan Hedberg is one of the — perhaps rare — people who believe the new map makes sense. He’s the editor and publisher for the Wet Mountain Tribune, the local paper in Westcliffe, and the commonality he sees is economic.

“The economy here in Custer County and all along the district, all the way up the upper [Arkansas River] … rests on people from the city — primarily the Denver front range, primarily the Denver Metro area — coming up here,” he explained. Tourism is a big driver in many of the district’s counties.

Hedberg takes a contrarian view that the rural-urban divide is a myth when you look at it through an economic lens. The highways in the district are economic arteries, heading from the heart that is the Denver area.

And noting that not all rural communities are the same, he flips the concept on its head, asking rhetorically, “What does [Westcliffe] have in common with Rifle, Colorado?” He points out it could take a full day to drive between the two and they don’t have direct economic connections.

For his part, Grantham notes one can always find something that connects communities near and far across Colorado, but “that doesn’t necessarily make it a logical constituency” or necessarily right to put them together.

There are some real differences between the rural and urban parts of District 7, from water management to local budgets (unlike urban communities that draw much of their funding from sales and property taxes, rural areas, especially those with lots of public lands, often depend on federal PILT payments) to public transportation (a big focus in urban areas but rarely one that reaches rural communities) to salaries.

However, some see rural-urban issues less as a divide and more of a device, one to frame policy discussions around.

Teller County Commission Board Chair Dan Williams admits there was not a lot of support for the new congressional map because of the fear that the specialized needs of its rural constituents “would get subsumed into another culture.”

“It'd be silly to say, ‘Well, we're all the same,’ because there were a lot of people that were upset when this happened,” he said. But “now everybody's looking at it as an opportunity.”

Now, optimistically, he said actually it’s “starting a good dialogue between both.” And at the center of that conversation will be the district's next congress member.

With incumbent Congressman Ed Perlmutter’s retirement, Democratic state Sen. Brittany Pettersen and Republican political newcomer Erik Aadland are competing for the rare open seat. Although the district leans about seven points in favor of Democrats, it’s expected to be a competitive race. And competitiveness can often, at least in theory, make for a more responsive representative.

“Lots of times, when somebody is new and eager, they have what, in my prior career we call ‘the fire in the belly,’” said Chaffee County Commissioner Keith Baker. “They are more ambitious or they do have an agenda and they do have a list of things they want to accomplish. There's advantages to that.”

Baker, a Democrat, mentioned he’s seen Pettersen campaigning in his county. In Fremont, Grantham said he’s seen Aadland. Williams, also a Republican, said both have come through Teller. Williams thinks a good representative will ensure that the economic arteries of the seventh, unlike actual biology, flow both ways to the benefit of the entire district.

While both candidates are from Jefferson County, Baker believes “the days are gone that they can stay in their urban power center and never pay any attention to the rural parts of their district. They do need votes from the rural parts of their district.”

And despite concerns in the rural counties, at least some of the seventh’s urban residents are glad they’re part of the district.

“I think they're going to be alright for keeping Colorado in the middle of the road, and not too far to the left [or] too far to the right,” said Rocky Germano in Lakewood.

At the southern end of the district, Anderson was hopeful that someone new would bring “fresh ideas,” but she added “time will tell” whether this new map ends up serving her county, or sidelining it.

Max Lubbers contributed reporting to this story.