On the first floor of Macky Auditorium, centrally located on CU Boulder’s campus, is a series of rooms with bright fabrics on the walls, artwork that celebrates Black and brown bodies, pillows decorated with Adinkra symbols, and portraits of Malcolm X and Michael Jordan.

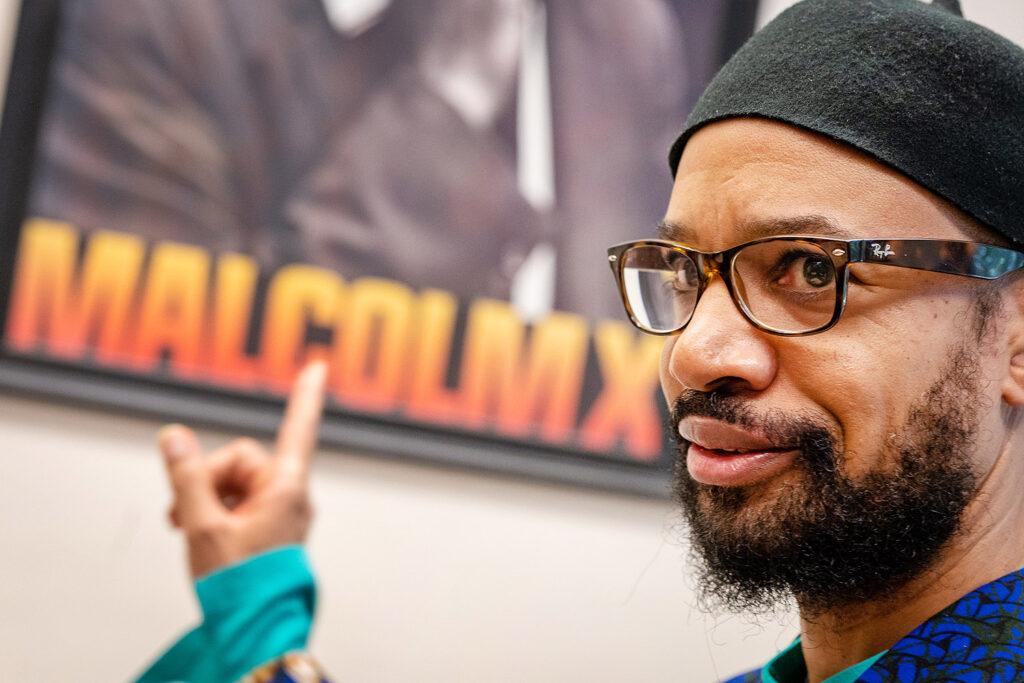

“We want to create that African village vibe in Boulder, Colorado,” said Reiland Rabaka, the director of CU Boulder’s new Center for African and African American Studies. With a laugh, he added, “Not going to be easy!”

Since he arrived on campus 17 years ago, Rabaka, a tenured professor in ethnic studies, has imagined what this center could be. Now it’s a reality. The CAAAS, which Rabaka pronounces as “the cause,” opened in August, with programming to support students academically, socially and mentally, in addition to the physical space for them to learn and socialize.

As much as the center will be a place for scholarly research and academic exploration, with a research program focused on African and African American Studies set to open in 2023, its role as a place to build community is equally important. Rabaka said an arts program, with a film series and other performing and visual arts, will also start next year.

Other public universities established centers focused on African and African American Studies decades ago. Rabaka laments that it has taken CU Boulder this long to build a similar center. But, he points out that on other campuses, it took activism from students and the community to bring about these centers in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. In Boulder, a campus where only about two percent of the student body is Black, it’s been difficult for people to find the time, patience and space to do the advocacy necessary to bring about a place like this.

“Some of the students and the staff and the faculty are so racially traumatized, it’s hard to think about building community and taking care of others when you actually need to take care of yourself,” Rabaka said.

Now he doesn’t want to focus on whether the center is overdue: “In African American studies, we say that there’s a tendency to over-focus on the tragedy. We also need to focus on the triumph. By the very fact that we have this center here at the University of Colorado Boulder, it’s a triumph,” he added.

John Robinson-Miller IV is associate director of the CAAAS and helped design the interior of the space. He wants students to feel pride in what they see, and to learn from it.

“We have Adinkra symbols, we have symbols and other iconography grounded in everything that we do. And through our programming, through our values, you will slowly start to learn what those things are,” Robinson-Miller said. “On day one, you may just see art and just see beautiful colors. But once you start coming to more and more programs, you’ll say, ‘Oh, I know exactly what that is.’”

“You can take what’s learned here and grow that out of the CAAAS,” said Ruth Woldemichael, a recent CU Boulder graduate who helped create the CAAAS as a student. “Our goal of the CAAAS is for students to connect but really gain tools to support them outside of this space and in the larger CU Boulder campus, in Boulder and in their personal lives, as well.”

Rabaka says the contributions of students have been critical in making the case to establish the center. The CAAAS’ official student co-founders – who include Woldemichael, and are now alumni – started an online petition that garnered more than 1,200 signatures, and met with campus administrators to advocate for the center. They also shaped key aspects of the center, like the focus on personal wellbeing.

The CAAAS plans to offer one-on-one counseling sessions, space to meditate, pray or mediate disagreements, and places to study and even defend their master’s theses.

“Some of the students feel incredibly alienated on the Boulder campus. Sometimes they’re the only African or African American in their department. So imagine if they can bring their committees and their family and their friends to a space where they can feel comfortable,” Rabaka said.

Woldemichal, who now lives in Denver and is a former president of the Black Student Alliance at CU Boulder, described a pattern of race-based discrimination, offensive comments and harmful experiences throughout her time in Boulder.

“Of course the center, the CAAAS, isn’t going to fix all the problems,” Woldemichal said. “You know, racism is not going to end just because we have this part of the Macky Auditorium. However, I think it can really work to build and sustain community and retention for people that look like us.”

As students like Woldemichael and faculty like Rabaka have navigated life at CU Boulder, they’ve formed a bond, and that bond is also part of how the CAAAS has come to exist.

“I understand some of the alienation, some of the isolation that they feel,” Rabaka said. The portion of faculty who identify as Black or African American is even lower than it is for students: 44 faculty members, representing less than two percent of the total. “I feel, oftentimes, closer to the students, because we come from similar backgrounds.”

His push to establish the CAAAS has been, in part, about having a safe space for these small numbers of students, faculty and staff to share things, like the latest Beyoncé video. Rabaka hopes it will help recruit and retain more Black students, staff and faculty, and ultimately change the entire culture around campus.

“When I go to the continent, people embrace me with open arms,” he said. “I want to live in an environment where we build a beloved community.” That includes building more anti-racist allies, both on campus and in the wider community.

“This is what institutional transformation looks like. A lot of people have been tap dancing around it. They know that things need to change here, but what do we do to actually make it change?”