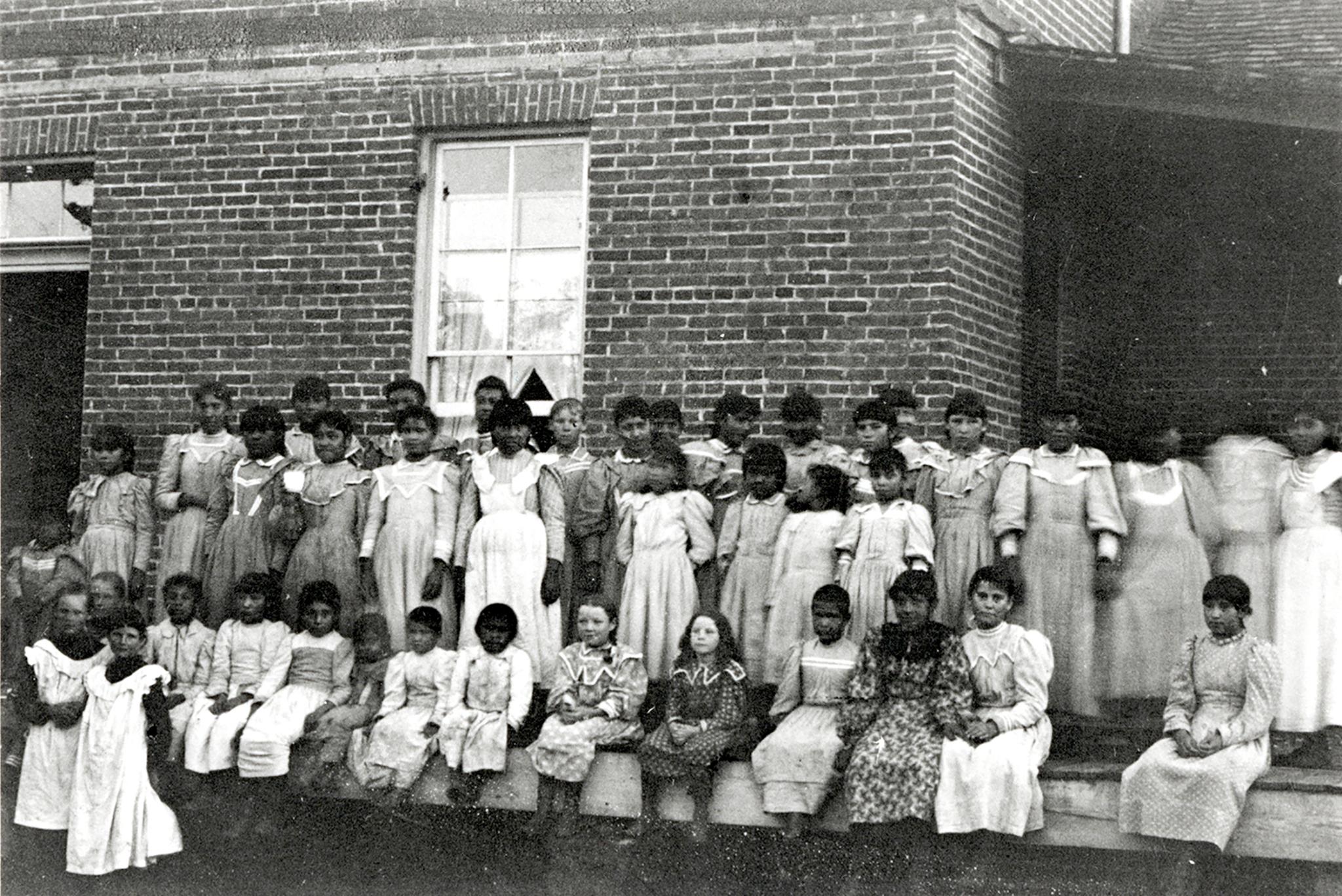

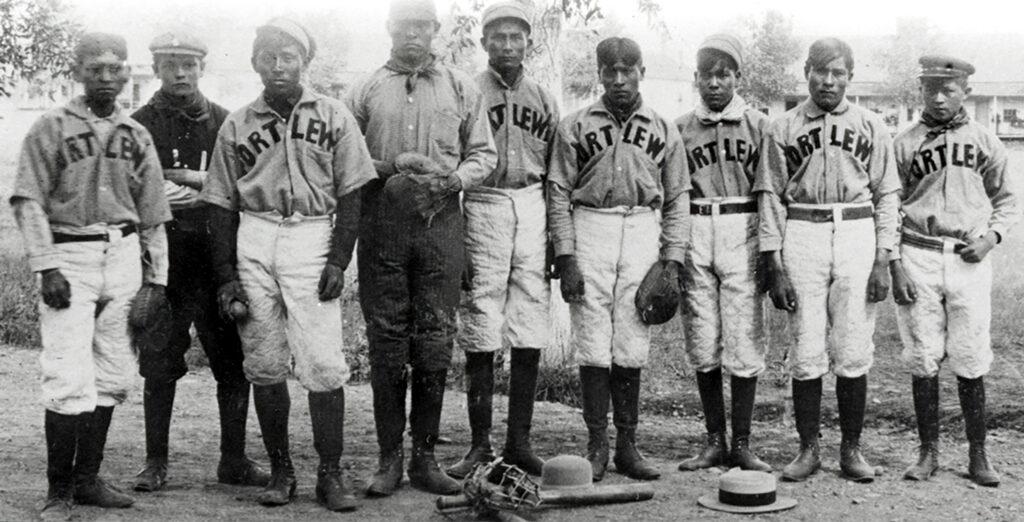

Researchers from History Colorado have started a state-mandated review of the former Indian boarding school on the grounds of Fort Lewis near Durango. The review will involve both archival research and physical examinations to uncover the extent of what happened at the boarding school when it operated between 1891 and 1910. And, one year after discoveries of mass graves at the sites of similar boarding schools in Canada, the survey in southwest Colorado will try to determine whether there are burial sites on the property.

In the research team’s first public update on its work Thursday, History Colorado’s Holly Norton, who is the state archaeologist, said the team is planning for tribal consultations this fall.

The researchers are required to make a final report by June 30, 2023, per legislation that established the research effort to “promote Coloradans' understanding of the physical and emotional abuse and deaths that occurred at federal Indian boarding schools.” But Norton said in her update, “I see this very much as the beginning of this effort. I think that what occurred at those schools is incredibly complex, it affected many, many people, and this is going to be a long-term effort. I think we’re going to be having these conversations for many years.”

“This study needs to say, ‘Here is what happened,’” said Rep. Barbara McLachlan, who co-sponsored the legislation. “Not just stories, but facts about what happened, where people might be buried, where artifacts might be buried, and what happened to people.” McLachlan, a Democrat from Durango, represents parts of the Four Corners area in Colorado’s state House.

The state’s research is meant to be a first step in “a roadmap for education and healing,” according to the legislation, though Rep. McLachlan isn’t sure what the next steps might be. They could include repatriating human remains to the tribes or allowing tribal blessings to occur at the boarding school and burial sites, among many other things.

Ute Mountain Ute Chairman Manuel Heart has ideas for what could come next.

Heart leads one of the nations whose children were forcibly removed and sent to the boarding school for the purpose of assimilation. The healing process should include investments in teaching children the languages, cultures and traditions that were taken away from their ancestors, he said.

“We want to teach these young children that are in school right now about how rich and how beautiful it is to be who we are as Natives, and to continue having this language,” he told the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs at Thursday’s meeting.

He suggested it may be appropriate for state lawmakers to fund things like the Ute Mountain Ute Kwiyagat Community Academy, which could help “bring back what was taken away.”

At a minimum, the roadmap will almost certainly include a plan for more public education about what occurred at the Fort Lewis boarding school, and at other sites within Colorado.

The state started a task force to study the Teller Institute site in Grand Junction in 2021. Norton said Thursday that researchers are further ahead at Teller, and this summer they worked on-site with tribal monitors.

A federal government inquiry into Indian boarding schools across the country reported in May 2022 that the U.S. operated or supported 408 such institutes across 37 states. The inquiry led by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, a member of Laguna Pueblo, confirmed that “the United States directly targeted American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children in pursuit of a policy of cultural assimilation that coincided with Indian territorial dispossession.”

“What they did in these schools was horrible. They took away culture, they cut hair, they wouldn’t let them speak their language, they wouldn’t let them dress like tribal members; [the children] didn’t get to go home, they were removed from families,” said Rep. McLachlan.

“These parents were lied to. They were lied to many years ago, and many, many times over. And we need to make amends for that lying,” she added.

The Colorado team’s archival research starts with records housed at the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, in Washington, D.C., Norton said. But those records are incomplete and are “almost never information from the perspectives of the students or the parents.” It would be “incredibly important” to do oral histories, Norton said, but right now “we don’t always know which questions to ask.”

The physical investigation will not be done through excavation; rather, Norton said the best practice at other former boarding school sites is to use multiple methods like LIDAR and ground-penetrating radar.

Sen. Don Coram, who represents southwestern Colorado in the state Senate and who co-sponsored the legislation mandating History Colorado’s research, said discussions about legislation to address Colorado’s history with Indian boarding schools have been ongoing for 10 years. He pointed to a lack of urgency, along with a legacy of mistrust between tribes and federal and state governments, as one reason the research has not begun until now.

“We have to learn from history,” Rep. McLachlan said. “It’s kind of like when you study the Holocaust. We just need to keep teaching and talking about it so that this never happens again.”